Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

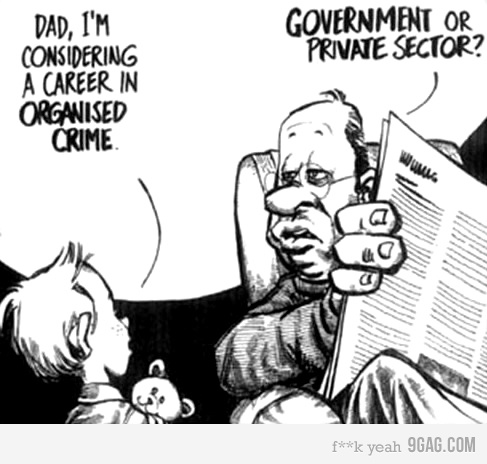

organised crime .....

Last December, Xanana Gusmão, the prime minister of Timor-Leste, was on an official visit to the world’s newest nation of South Sudan when he received an urgent call from Dili. Officers from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Federal Police had just taken files and computers from the Canberra office of Bernard Collaery, one of the lawyers advising Timor-Leste in a dispute with Australia over a treaty that divided the spoils of the $40 billion Greater Sunrise oil and gas field.

Gusmão was also told of a simultaneous raid on the Canberra home of Timor-Leste’s key secret witness in the dispute. This former Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) agent had reportedly provided an affidavit alleging that Australian spies bugged the Timor-Leste government’s cabinet room in order to secure a commercial advantage for Australia during treaty negotiations in 2004. His passport had been confiscated in the raid, preventing him from travelling to The Hague, where the Permanent Court of Arbitration was due to hear Timor-Leste’s application to overturn the treaty.

Gusmão described the raids as “unconscionable and unacceptable conduct”. Lawyers for his country demanded the immediate return of the seized documents; when Australia refused, Timor-Leste sought an urgent hearing at the International Court of Justice, also in The Hague.

The Canberra raids were a spectacularly public example of the usually secret, win-at-all-costs tactics Australia has employed since the early 1970s to secure sovereignty over oil and gas in the Timor Sea.

The Greater Sunrise field lies 450 kilometres north-west of Darwin, but only 150 kilometres south-east of Timor-Leste. Australia first issued exploration permits in the Timor Sea to an Australian company, Woodside Petroleum, in 1963. At that time the island of Timor was split down the middle. The western half was part of Indonesia, the eastern half was Portuguese. Australia maintained that its sovereignty extended to the edge of its continental shelf, or more than two thirds of the way to the island of Timor.

Portugal disputed Australia’s claim and insisted that the boundary should be based on the median line between Australia and Timor, in accordance with international law.

Indonesia’s President Suharto was more compliant. He was keen to demonstrate that he was a friend of the West, and in 1972 he signed away rights in favour of Australia in relation to a large area north of the median line. The dispute with Portugal left a gap in the boundary line between Australia and Portuguese Timor – the Timor Gap.

Woodside announced its discovery of Greater Sunrise in 1974. The new Australia–Indonesia boundary put 80% of the potential bonanza on the Australian side; however, the field stretched into waters off Portuguese Timor, which meant Australia couldn’t guarantee full sovereignty until the gap in the boundary was closed.

A revolution in Portugal spawned an opportunity to do just that. The new government announced that it would grant all colonies independence. Australia and the United States acceded to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in December 1975, ostensibly to prevent communism getting a foothold in the region. However, Australia had an additional motivation: officials believed Indonesia could be persuaded to close the gap in the maritime boundary by joining the dots, leaving 100% of Greater Sunrise on the Australian side of the line.

Despite thousands of deaths during the first year of the invasion, Australia moved diplomatically closer to Indonesia. Less than a year later, the Suharto government said it would be prepared to close the gap in the maritime border on terms favourable to Australian interests. Australia would have to formally recognise Indonesia’s sovereignty over East Timor first. In January 1978, Australia duly became the only Western government to recognise East Timor as part of Indonesia. Two months later, Australia and Indonesia commenced negotiations to close the gap in the maritime boundary.

Meanwhile, according to a report commissioned by the United Nations, “Indonesian military commanders ordered, supported and condoned systematic and widespread unlawful killings and enforced disappearances” in East Timor between 1978 and 1979, and allowed famine to reach “catastrophic proportions”. Despite the reports of atrocities on its northern doorstep, Australia continued to press Indonesia to close the gap, but the power balance had shifted. The Indonesian foreign minister publicly complained that Australia had taken Indonesia “to the cleaners” with the 1972 treaty, and now demanded a median line boundary.

Negotiations dragged on until 1989, when Indonesia and Australia agreed to share resources in a joint development zone. The Australian foreign minister, Gareth Evans, and his Indonesian counterpart, Ali Alatas, signed the Timor Gap Treaty as they flew over the Timor Sea. Evans called for champagne – more than 80% of Greater Sunrise was still on Australia’s side.

The end of Suharto’s rule, however, led to a UN-sponsored self-determination vote in East Timor in 1999. When the Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence, Indonesia immediately lost all authority to exercise jurisdiction off East Timor’s coast. The Timor Gap Treaty became invalid. Suddenly Australia had no rights north of the median line – no rights to Greater Sunrise. Worse still for Australia, in 1994 it had ratified the Convention on the Law of the Sea, which confirmed the median line principle.

Australia had to start its treaty push all over again. After Indonesia’s withdrawal from East Timor, the UN established an interim administration to govern the territory in preparation for a new parliamentary system. Australia lined up Woodside and other resource companies to argue that the gas fields could start funnelling desperately needed revenue to the new nation if the Timor Gap Treaty boundaries were promptly endorsed. Rather than wait for a Timorese government to form, the UN administration locked the Timorese into the same boundaries Australia had negotiated with Indonesia. Soon after, Australia withdrew from the maritime boundary jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice. On 20 May 2002, with no access to an independent umpire, and desperate for revenue, the new nation of Timor-Leste signed the heads of agreement for a new treaty with Australia.

But a further treaty was needed to split the potential revenue. Alexander Downer, Australia’s minister for foreign affairs, who would go on to work as a lobbyist for Woodside after leaving parliament, stepped in to lead the negotiations. The Timorese had taken precautions in case their phone conversations were being intercepted, but they had no idea the Australians had allegedly (under the auspices of an aid program to renovate government buildings) placed bugs in the walls of the cabinet room where they met to discuss tactics. Although the resulting 2006 treaty saw Timor-Leste increase its share of Greater Sunrise revenue to 50% of the whole field (not just the 20% in the joint development zone), the boundaries remained unchanged. Australia walked away with the rights to billions of dollars that, if not for the treaty, would otherwise flow to Timor-Leste. An even bigger win for Australia was the clause that prohibited Timor-Leste from seeking to re-open maritime boundary negotiations for the next 50 years, by which time resources would likely be depleted.

All in all, it’s quite a saga, even without the raids. For more than 40 years, Australia has played hardball with some of the poorest people on earth. It is one thing to be caught out spying to protect citizens from terrorism or for national security, but the allegation that Australia spied for commercial gain, under the cover of an aid program, is something else entirely.

Even Prime Minister Tony Abbott felt compelled to touch on this distinction after American whistleblower Edward Snowden leaked information indicating that Australia spied on Indonesian officials engaged in trade talks over prawn exports. Abbott responded on ABC radio: “We use it [surveillance] … to protect our citizens and the citizens of other countries, and we certainly don’t use it for commercial purposes.”

The Permanent Court of Arbitration will see about that in due course. In the meantime, the International Court of Justice handed down its interim decision on the Canberra raids on 3 March, ordering Australia to seal the seized documents and to keep them sealed until its final decision.

The court also directed, by 15 votes to one, that “Australia shall not interfere in any way in communications between Timor-Leste and its legal advisers in connection with the pending Arbitration”.

The one dissenting judge to this order was Australia’s appointment to the court.

- By John Richardson at 1 Apr 2014 - 11:21am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

9 min 6 sec ago

17 min 1 sec ago

35 min 2 sec ago

3 hours 13 min ago

3 hours 34 min ago

3 hours 38 min ago

4 hours 17 min ago

3 hours 46 min ago

8 hours 34 min ago

9 hours 33 min ago