Search

Recent comments

- UK-israhell.....

4 hours 6 min ago - albania.....

4 hours 14 min ago - israhell crap.....

4 hours 32 min ago - waste of cash....

7 hours 10 min ago - marles' bluster....

7 hours 32 min ago - fascism français....

7 hours 36 min ago - russian subs in swedish waters....

8 hours 15 min ago - more polling....

7 hours 43 min ago - they know....

12 hours 32 min ago - past readings....

13 hours 31 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

cultural, economic and sexual inspiration from ancient greece's golden age — 600 BC...

In his poems, Solon portrays Athens as being under threat from the unrestrained greed and arrogance of its citizens.[99] Even the earth (Gaia), the mighty mother of the gods, had been enslaved.[100] The visible symbol of this perversion of the natural and social order was a boundary marker called a horos, a wooden or stone pillar indicating that a farmer was in debt or under contractual obligation to someone else, either a noble patron or a creditor.[101] Up until Solon's time, land was the inalienable property of a family or clan[102] and it could not be sold or mortgaged. This was no disadvantage to a clan with large landholdings since it could always rent out farms in a sharecropping system. A family struggling on a small farm however could not use the farm as security for a loan even if it owned the farm. Instead the farmer would have to offer himself and his family as security, providing some form of slave labour in lieu of repayment. Equally, a family might voluntarily pledge part of its farm income or labour to a powerful clan in return for its protection. Farmers subject to these sorts of arrangements were loosely known as hektemoroi[103] indicating that they either paid or kept a sixth of a farm's annual yield.[104][105][106] In the event of 'bankruptcy', or failure to honour the contract stipulated by the horoi, farmers and their families could in fact be sold into slavery.

Solon's reform of these injustices was later known and celebrated among Athenians as the Seisachtheia (shaking off of burdens).[107][108] As with all his reforms, there is considerable scholarly debate about its real significance. Many scholars are content to accept the account given by the ancient sources, interpreting it as a cancellation of debts, while others interpret it as the abolition of a type of feudal relationship, and some prefer to explore new possibilities for interpretation.[4] The reforms included:

- annulment of all contracts symbolised by the horoi.[109]

- prohibition on a debtor's person being used as security for a loan.[107][108]

- release of all Athenians who had been enslaved.[109]

The removal of the horoi clearly provided immediate economic relief for the most oppressed group in Attica, and it also brought an immediate end to the enslavement of Athenians by their countrymen. Some Athenians had already been sold into slavery abroad and some had fled abroad to escape enslavement – Solon proudly records in verse the return of this diaspora.[110] It has been cynically observed, however, that few of these unfortunates were likely to have been recovered.[111] It has been observed also that the seisachtheia not only removed slavery and accumulated debt, it also removed the ordinary farmer's only means of obtaining further credit.[112]

The seisachtheia however was merely one set of reforms within a broader agenda of moral reformation. Other reforms included:

- the abolition of extravagant dowries.[113]

- legislation against abuses within the system of inheritance, specifically with relation to the epikleros (i.e. a female who had no brothers to inherit her father's property and who was traditionally required to marry her nearest paternal relative in order to produce an heir to her father's estate).[114]

- entitlement of any citizen to take legal action on behalf of another.[115][116]

- the disenfranchisement of any citizen who might refuse to take up arms in times of civil strife, a measure that was intended to counteract dangerous levels of political apathy.[117][118][119][120][121]

...

As a regulator of Athenian society, Solon, according to some authors, also formalized its sexual mores. According to a surviving fragment from a work ("Brothers") by the comic playwright Philemon,[141] Solon established publicly funded brothels at Athens in order to "democratize" the availability of sexual pleasure.[142] While the veracity of this comic account is open to doubt, at least one modern author considers it significant that in Classical Athens, three hundred or so years after the death of Solon, there existed a discourse that associated his reforms with an increased availability of heterosexual pleasure.[143]

Ancient authors also say that Solon regulated pederastic relationships in Athens; this has been presented as an adaptation of custom to the new structure of the polis.[144][145] According to various authors, ancient lawgivers (and therefore Solon by implication) drew up a set of laws that were intended to promote and safeguard the institution of pederasty and to control abuses against freeborn boys. In particular, the orator Aeschines cites laws excluding slaves from wrestling halls and forbidding them to enter pederastic relationships with the sons of citizens.[146] Accounts of Solon's laws by 4th century orators like Aeschines, however, are considered unreliable for a number of reasons;[6][147][148]

Attic pleaders did not hesitate to attribute to him (Solon) any law which suited their case, and later writers had no criterion by which to distinguish earlier from later works. Nor can any complete and authentic collection of his statutes have survived for ancient scholars to consult.[149]

Besides the alleged legislative aspect of Solon's involvement with pederasty, there were also suggestions of personal involvement. According to some ancient authors Solon had taken the future tyrant Peisistratos as his eromenos. Aristotle, writing around 330 BC, attempted to refute that belief, claiming that "those are manifestly talking nonsense who pretend that Solon was the lover of Peisistratos, for their ages do not admit of it," as Solon was about thirty years older than Peisistratos.[150] Nevertheless, the tradition persisted. Four centuries later Plutarch ignored Aristotle's skepticism[151] and recorded the following anecdote, supplemented with his own conjectures:

And they say Solon loved [Peisistratos]; and that is the reason, I suppose, that when afterwards they differed about the government, their enmity never produced any hot and violent passion, they remembered their old kindnesses, and retained "Still in its embers living the strong fire" of their love and dear affection.

Read more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon

- By Gus Leonisky at 3 Jan 2016 - 4:50pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the more things change...

During Solon's time, many Greek city-states had seen the emergence of tyrants, opportunistic noblemen who had taken power on behalf of sectional interests. In Sicyon,Cleisthenes had usurped power on behalf of an Ionian minority. In Megara, Theagenes had come to power as an enemy of the local oligarchs. The son-in-law of Theagenes, an Athenian nobleman named Cylon, made an unsuccessful attempt to seize power in Athens in 632 BC. Solon was described by Plutarch as having been temporarily awarded autocraticpowers by Athenian citizens on the grounds that he had the "wisdom" to sort out their differences for them in a peaceful and equitable manner.[29] According to ancient sources,[30][31] he obtained these powers when he was elected eponymous archon (594/3 BC). Some modern scholars believe these powers were in fact granted some years after Solon had been archon, when he would have been a member of the Areopagus and probably a more respected statesman by his (aristocratic) peers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon

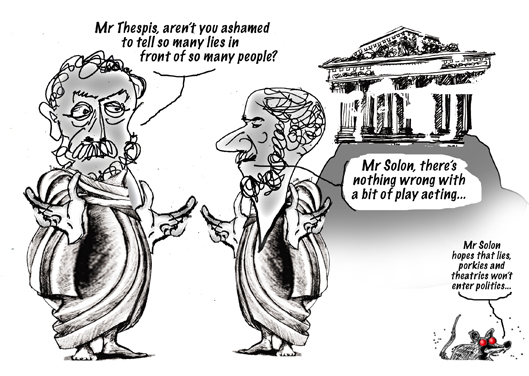

the why of the toon at top...

From Plutarch (written around 100 AD) — Manuscript of Parallel Lives (10th century), printed 1517, interpreted by Gus (2016):

Thespis, began to act tragedies, and because it was new, entertaining the multitude without competition yet, Solon went to see him after the play and confronted Thespis, asking him if he was not ashamed of telling so many lies in front of such a large crowd. Thespis replied that it did no harm to say or do so in a play. Solon hit the ground forcefully with his walking stick and argued that "should we honour and commend such acting, we shall discover that such lies and action will seep into the real interactions (of politics, of commerce and of life in general)".

"fair rules"... are few and far in between these days...

Did political decentralization foster classical civilization? That is one of the central claims of this fascinating new work of analytical history by the Stanford political scientist and classicist Josiah Ober.

Ober uses the tools of institutional political economy to explore the causes of economic and cultural “efflorescence” in ancient Greece. Rather than focusing on the impacts wrought by individual decision-makers animated by distinctive outlooks or on the after-effects of great fortuities, Ober does social science, using the evidence of history to test hypotheses about the significance of political institutions and economic policy to human progress.

“Fair rules and competition within a marketlike ecology of states promoted capital investment, innovation, and rational cooperation in a context of low transaction costs.” This is the hypothesis Ober tests on the ancient Greek city-state (polis), which persisted from roughly 600 BC to the Roman conquest in the early second century BC. There are two parts to the hypothesis: one has to do with the political institutions Greek city-states adopted (fair versus unfair rules), and the other has to do with the change over time in economic integration and military rivalry among independent poleis (more or less competition). He takes advantage of the kaleidoscopic variety of institutional forms among the Greek states to investigate how their different political rules affected incentives for investment and exchange and therefore economic growth. He also explores how competition and rivalry over time affected the proportion of Greek city-states that adopted institutions that created good incentives.

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/when-greece-was-rich-and-why/

Without wanting to recognise it, we have reached the limits of this little planet on many fronts. And as the humans species pushed towards these limits, the rest of nature has been under threat of collapse. Such collapse does not give strong signs, though are a lot of signs of nature under stress in many quarters. But suddenly we get the zika virus, the warmer climes and many big species of mammals now only surviving as a terrible prospect in zoos. Suddenly, nature collapses...........