Search

Recent comments

- they know....

1 hour 50 min ago - past readings....

2 hours 49 min ago - jihadist bob.....

2 hours 56 min ago - macronicon.....

4 hours 50 min ago - fascist liberals....

4 hours 51 min ago - china

8 hours 26 min ago - google bias...

1 day 1 hour ago - other games....

1 day 1 hour ago - נקמה (revenge)....

1 day 2 hours ago - "the west won!"....

1 day 4 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

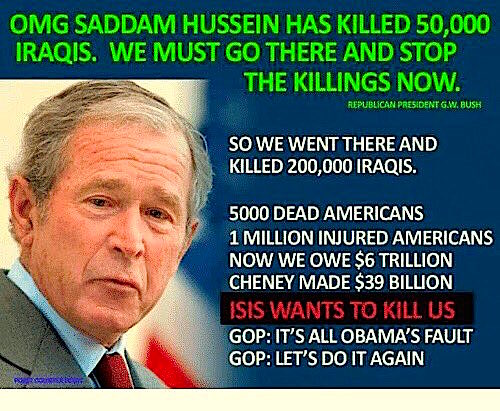

a crime, with not a single good intention...

Andrew Bacevich reviews Michael Mazarr’s Leap of Faith, and he rejects the author’s contention that the Iraq war was the product of good intentions gone awry:

To explain all of this in terms of a misplaced messianic impulse — the self-described indispensable nation having a bad run of luck — may play well in Washington, where serious introspection is rarely welcome. Yet, ultimately, such an explanation amounts to little more than a dodge. After all, altruism rarely if ever provides an adequate explanation for the actions of a great power. Exempting the United States from that proposition, as Mazarr does, entails its own spectacular leap of faith.

Bacevich is right that the Iraq war was “more like a crime, compounded by the stupefying incompetence of those who embarked upon a patently illegal preventive war out of a sense of panic induced by the events of 9/11,” and it was a crime committed for the worst reasons rather than the best motives. The goal of the war was to crush an adversary in order to send a message to the rest of the world about American dominance and our government’s willingness to use force to achieve its ends, but a war waged for a “demonstration effect” ended up sending a very different message to the world.

Waging an illegal preventive war cannot be noble and cannot be done with “good intentions.” To embark on an unnecessary war in violation of another state’s sovereignty and international law because you claim to be afraid of what they might do to you at some point in the future is nothing other than aggression covered up by a weak excuse. It is the act of a bully looking to lash out at a convenient target. Calling the Iraq war a “tragedy” implies that the U.S. had a legitimate reason to go to war against Iraq in 2003, but there was no legitimate reason and anyone who thought things through could see that at the time. The war was inherently unjust, as all preventive wars always are, and it makes no difference whether some ideologues claimed to have high-minded reasons for committing a grave injustice against tens of millions of people.

There are a lot of foreign policy professionals in the U.S. that very much want to believe that the U.S. commits crimes like the Iraq war out of the best of intentions. It doesn’t make the war any less destructive, and it doesn’t mean that there are any fewer lives lost in senseless conflict, but it somehow comforts them to think that the U.S. destroys entire countries out of a desire to help rather than harm. What matters most in the end is the effects of our government’s policies, but it is important to understand that no one supports wars of aggression for genuinely good or moral reasons. The moralizing rhetoric is an attempt to dress up an ugly policy as something other than what it is. The Iraq war didn’t simply turn out badly. It was wrong from the outset. Any account of the war that fails to grasp that has missed an essential truth.

Read more:

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/larison/the-iraq-war-was-a-crime...

- By Gus Leonisky at 22 Apr 2019 - 3:34pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

they lied...

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/11276

pravda in english is no more?

I believe Pravda in English has been "terminated"... I do not know why but I suspect foul play. This is what comes up when trying to log in:

I will have to read it in Russian, but it's a bit rusty...

embracing foreign policy restraint...

Please disregard the old post above this one...

-----------------------

Now something from Andrew Bacevich — president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and TAC’s writer-at-large.

Three days after the presidential election, with the outcome still hanging in the balance, Roger Cohen of the New York Times published a column that offered his take on the ongoing controversy. “The People Versus Donald Trump,” read the headline. “They want him to go, and he won’t listen,” added the subhead.

Now there is nothing unusual in a newspaper columnist opining about what “the people” want, even one who, as in Cohen’s case, doesn’t live in the United States. But Cohen’s judgment overlooks this striking fact: while Donald Trump may have lost the presidency, he won millions more votes this year than he did in 2016. His total haul of nearly 70 million—exceeding Barack Obama’s total when elected to his first term in 2008—suggests that some approximation of “the people” were keen for him to remain in office for another four years.

Furthermore, Joe Biden’s narrow victory in what he himself described as “the most important election in our lifetime” leaves the national political landscape remarkably unchanged. Democratic hopes of gaining control of the Senate appear unlikely to materialize. In the House of Representatives, the party actually lost seats. Biden is a winner with no coattails. The electorate that has ousted Trump from the presidency has refrained from endorsing a leftward shift in American politics. Biden brings to office a mandate that is somewhere between slight and non-existent.

So like it or not, even as Trump himself leaves the White House, the forces that vaulted him to the center of national politics will persist. To revert to Cohen’s formulation, on matters related to race, religion, culture, climate, and the economy, “the people” are of two minds—or, more accurately, of several minds. As one prominent expression of the cleavages that have fractured our country, Trumpism, with or without Trump, will continue to play a large role in national politics for some time to come.

Biden’s vow to heal those cleavages is necessary, commendable, and undoubtedly heartfelt. Yet doing so will take more than reassuring words from a decent but aging career politician presiding over a divided government. Even though the outcome of the election now appears settled, don’t expect Trump’s legions to climb aboard the Biden bandwagon.

Let me suggest that there is one arena where Biden might actually make some progress toward fulfilling his promise to “save America’s soul.” I refer to foreign policy.

Progress here will require changing course on an issue that went almost entirely unmentioned during the run-up to the election: our nation’s disastrous affinity for war. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, war has become the principal signature of American statecraft. Over the course of three decades of sustained military activism, U.S. troops have suffered terrible losses while winning few conclusive victories. “Forever wars” in places like Afghanistan and Iraq have added trillions of dollars to the national debt.

Responsibility for this record of squandered blood and treasure rests with both parties. Democrats and Republicans have squabbled over any number of issues. But when it comes to military power and its utility, a broad consensus has prevailed. That consensus finds expression in ever-increasing Pentagon budgets, an expansive global military presence, and a penchant for armed intervention in distant places.

In Washington, everyone supports the troops. Too few bother to think critically about what the troops are actually doing, where, and at what cost. Patriotism carries the taint of militarism.

On that score, Donald Trump was an exception. If the train wreck of his presidency has any redeeming feature, it is found in his recognition that “endless wars” do not serve the national interest. Of course, Trump being Trump, he demonstrated neither the attention span nor the constancy of purpose to make good on his vow to end them. Even so, his repeated promise to do so resonated with his followers. Put simply, Trumpism contains a strong antiwar component.

So if President-elect Biden is serious about bringing the country together, here is one place where he might find common ground with the 70 million who preferred his opponent. Pro-Trumpers will never agree with Biden on abortion, gun ownership, climate change, or “socialism.” But if a Biden administration restores a measure of prudence to U.S. military policy, they just might respond favorably.

What might prudence look like in practice? Greater restraint in the use of force offers one obvious example. Abandoning regime change as a foreign policy objective offers another. Reducing military spending in favor of addressing neglected needs at home offers a third.

Nothing in Joe Biden’s long career suggests that he will become an overtly antiwar president. But should he foster an approach to national security that emphasizes military restraint and creative diplomacy, he just might make a first step toward healing a broken democracy.

Andrew Bacevich is president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and TAC’s writer-at-large.

Read more:

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/biden-can-start-to-heal-america-by-embracing-foreign-policy-restraint/

See also: joe biden is god...

donald is "an embarrassment"...

trump quietly awaits defeat on a car park between a dildo store and a crematorium....

donald trump nach der us wahl der hausbesetzer....and

understanding the military mind...Read from top.