Search

Recent comments

- ukraine's agony has not started yet....

16 hours 20 min ago - all defeated.....

16 hours 32 min ago - beyond crime.....

17 hours 22 min ago - the end....

17 hours 33 min ago - odessa....

18 hours 40 min ago - weitz....

20 hours 30 min ago - bidenomics BS.....

20 hours 44 min ago - the defeat of ukraine is coming....

21 hours 32 min ago - paris is sick....

1 day 8 hours ago - German spies?....

1 day 10 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

plea bargaining .....

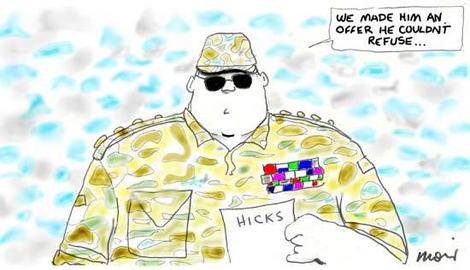

So, federal water burglar & recovering lawyer, malcolm moneybags, has questioned why David Hicks did not try to negotiate a plea bargain earlier?

Let’s see …..

A trial that was uncomfortably close to Stalinist theatre

Robert Richter

April 1, 2007

‘David Hicks is coming home. At what price? Let us take stock. The charade that took place at Guantanamo Bay would have done Stalin's show trials proud. First there was indefinite detention without charge. Then there was the torture, however the Bush lawyers, including his Attorney-General, might choose to describe it. Then there was the extorted confession of guilt.

Whatever Hicks may have done, the theatre of a voluntary plea of guilty when the choice is "rot in hell or say it's true so you can go home" is worthy of The Grand Inquisitor. In Stalin's as well as the German show trials of the 1930s, the essence of the display was the public confession, followed by the sentence. The Iranians and al-Qaeda still practise it, but isn't that why we declared a War on Terror?

Then there was the silence. In the show trials, it was enforced by execution. In this instance it is enforced by threats of further punishment in both the US and Australia. The implications of the gag are staggering when added to the wholesale destruction of the rule of law.

Hundreds of years of what constituted the rule of law have been jettisoned so that Howard, Ruddock and Downer can pretend that Hicks is off their election agenda. Forget habeas corpus. Forget retrospective legislation. Forget coerced evidence and confessions. Forget commissions in which guilt has been predetermined. Forget prosecutors being judges in their own cause.

It's OK as long as those who aided and abetted the destruction of these principles are back in office and remain unaccountable and can perpetuate the lie. If they lose office, the true story will emerge - but may no longer have impact.

The deal was simple: go home. Shut up. If you dare to say you had no choice but to plead guilty, the US Military Commission will find you guilty of perjury and will call in a full seven-year sentence, over and above the five you've suffered unconvicted and uncharged. That will mean the Australian Attorney-General may not release you on licence for another seven years, or will - with the additional gags of control orders and other available means - make sure you cannot tell anyone what happened.

Apart from the loss of fundamental guarantees of freedom, another freedom - speech - is garrotted.

The best thing one can say about the process is that one day there may be a reckoning for this despicable episode, in which Australian ministers, all the way down from the Prime Minister, have been party to the commission of grave crimes under the Australian Criminal Code 1995, divisions 104 (Harming Australians Overseas) and 268D (denying a fair trial), because they have been criminally complicit under section 11.2.

By the time the US Supreme Court strikes down the whole festering sore in a couple of years - which most constitutional lawyers believe it will - we can only hope there will be another attorney-general in Australia who will have the guts to authorise proceedings against those who "aided, abetted, counselled or procured" the commission of the crimes to which I have referred. Let us not forget the war crimes trials after World War II, in which the German Nazi judges who prostituted their duty in the service of the political ideology that put them there were put on trial for what they did.

It may only be then that the full horror of what we allowed to happen to the rule of law in the name of political expediency will be revealed.’

Robert Richter, QC, is a Melbourne barrister.

- By John Richardson at 2 Apr 2007 - 7:48pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

totalitarian thugs .....

from Crikey …..

What a string of circumstances. David Hicks gets plucked from an Afghani taxi. He gets flogged off to a posse of passing American spooks for $1,000. Then, after five years in US solitary confinement without a trial, he finds himself professing his guilt to terror-related offences and gets sentenced to a further nine months in some as-yet-unnamed South Australian prison.

But wait, there's more. This story actually gets worse, for Hicks has now been banned from even talking about his experiences for twelve months, the duration of the Australian federal election campaign. Even Attorney-General Philip Ruddock today admits that he can't recall anything like the Hicks gag in his long and legally varied experience.

This is a gag that is unconstitutional in its country of origin. It is a gag that is legally dubious in Australia. It is a gag that contravenes every shred of the notion of free speech.

It is a gag that makes the Australian government - whose hand is so stealthily and transparently behind it - look like a bunch of totalitarian thugs.

and Crikey legal correspondent Greg Barns writes:

I agree that I will not communicate with the media in any way regarding the illegal conduct alleged in the charge and the specifications or about the circumstances surrounding my capture and detention as an unlawful enemy combatant for a period of one (1) year. I agree that this includes any direct or indirect communication made by me, my family members, my assigns, or any other third party made on my behalf.

David Hicks plea agreement 26 March 2007

An attempt to tape the mouth of an Australian citizen in such a way must surely be the subject of a feisty legal challenge.

Firstly, the gag order on Mr Hicks was made in weird legal limbo. That is, the rules applying to the Guantanamo Bay legal process are not those which apply in the American criminal justice system. And it is arguable, according to a series of US court decisions, confirmed yesterday by the US Supreme Court, that the Guantanamo Bay military tribunals and the rules which they apply are not always subject to the protections granted by the US Constitution.

Then there is the question of how such a gag order can apply in Australia. There is no doubt that under the conventional prisoner exchange agreement that Australia has with countries like the US, sentences handed down by a court in the foreign jurisdiction can be served in an Australian prison. And in civil law, court orders made in the US can, subject to certain limitations, be registered as a foreign judgment in Australian courts.

But under what statute or pursuant to which line of case law does the Australian government say it can enforce the gag order on Mr Hicks? The Attorney-General Philip Ruddock doesn’t seem to have worked this out yet. As Mr Ruddock has acknowledged, we are in uncharted legal waters here. A point also made yesterday by leading human rights and criminal lawyer Rob Stary, ‘Jihad’ Jack Thomas’s lawyer, who said yesterday that the gag order on Mr Hicks was unprecedented in Australian criminal law and procedure.

Will Mr Ruddock, for example, seek to impose a control order under the anti-terrorism laws on Mr Hicks, even while he is in prison, to prevent him from speaking with the media?

Or will he seek to have special legislation passed to achieve this aim?

No doubt officers of the federal Attorney-General's department are busily scouring the statute books and examining case law to give Mr Ruddock an answer to this intriguing legal question.

But in any event, it must surely be on the cards that there will be a challenge to any attempt to enforce the gag order in Australia. Not simply because it sets a very real and dangerous precedent – one can imagine state and federal ministers who don’t want individuals revealing police brutality and abuse of human rights in prisons citing the gag order on Mr Hicks as justification for shutting up victims of such abuse – but because there are potentially some constitutional considerations that come into play.

Since 1992, in a case involving the former Labor MP Andrew Theophanous, the High Court has determined that there are implied rights to free speech and communication when it comes to discussion of issues about government and politics, particularly in the context of elections. This is known as the implied freedom of political communication.

Surely the circumstance of the detention of Mr Hicks is a matter concerning politics or government. His arrest and detention has been the subject of heated political discourse. If the media publishes an interview with Mr Hicks about these matters are they simply not utilising that implied freedom?

Perhaps Mr Hicks will have his mouth untaped after all.