Search

Recent comments

- google bias...

3 hours 24 min ago - other games....

3 hours 27 min ago - נקמה (revenge)....

4 hours 27 min ago - "the west won!"....

6 hours 30 min ago - wagenknecht......

7 hours 11 min ago - the game of war....

9 hours 35 min ago - three packages....

10 hours 55 min ago - russian oil.....

11 hours 2 min ago - crime against peace....

19 hours 14 min ago - why is Germany supporting the ukrainian nazis?....

20 hours 27 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

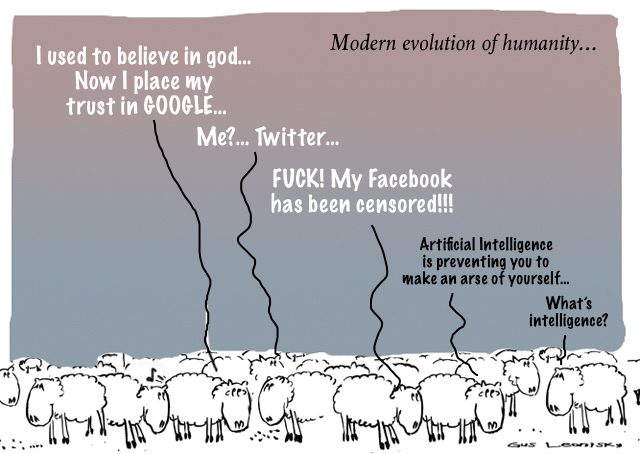

are we becoming more controlled?...

AI

AI

Are you scared yet, human?

This Panorama/4C program looks at the problems of Artificial Intelligence (https://iview.abc.net.au/video/NC2103H026S00) … We have done our best here to follow the AI caper since the inception of this site (2005)... If you live outside Australia, your link might be different:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000wft2/sign/panorama-are-you-scared-yet-human

or https://m.facebook.com/watch/?v=556586022146617&_rdr

or https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p09hzxb1

One thing we need to say from the beginning, this electronic relationship between us, me, you and an Obeid lamppost, the program, the TV and the people who made it could not exist without ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. In times of Covid-19, without “Artificial Intelligence” to help connect people and calculate the probable reactivity to vaccines on a human proportion level, we would be stuffed. But we could add that the virus may not have spread around the planet, had AI of various influences in labs and aeroplanes not been in place.

Despite having to be in Lockdowns and living in isolation for a few more weeks in Sydney, we are not fully separated from other humans because of our electronic communication gizmos such as the internet platforms that AI controls, mostly automatically… Meanwhile, the inevitable creation of autonomous drones that can “calculate” friends or foes probabilities and then shoot, is a bit like creating a moving minefield in the sky rather than laying mines in the dirt and record their positions so we don’t blow ourselves up.

Many people are worried that we are becoming controlled. But we have been controlled by psychological manipulation since our personal year dot. The main problem here is that our secret activities (we don’t have any, do we?) are hemmed in by spying technologies that infiltrate our moral compass and whack us automatically, should we misbehave. And this is the price to pay for our excellent comforts. The alternative is to be hungry and chase our tail for fun, under the rain.

Is our fridge going to tell us that we’ve drunk enough wine or beer today? Is our washing machine going to shame us for our clothes being too dirty and stained by armpit juice? Or will we be like the emperor and his new clothes?

Do we need Artificial Intelligence to get rid of our psychopaths that rule politics? Hum… Could we have a machine that sends electric shock to a minister every time the bugger tries to rort the system? That should not be too hard to set up, should it?…

We can hope.

Whatever we think, AI is here to stay and rule our life. May as well manage it so that it improves our understanding of place on this little planet.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 Aug 2021 - 7:25pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

mining smartphones...

If you had a tonne of ore from a gold mine, and a tonne of iPhones, which is likely to contain more gold? What about silver?

You've probably guessed the reason for the question is that the answer is surprising. And yes, in both cases, it's the devices that are a richer source of the precious metals.

In fact, the metals for all Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic medals came from recycled e-waste.

Over two years, the organisers gathered enough gold, silver and bronze from small electronic devices to make the almost 5,000 medals awarded to the athletes.

And it's not just our computers and phones.

Everything from electric cars to wind turbines and solar panels — things we need to transition the world to net-zero emissions — require an array of metals, like silver, palladium, platinum, copper, aluminium and rare-earths, such as neodymium.

So where will we get them from? Will we have enough? And what role can recycling and reuse play in ensuring we can supply our technology needs into the future?

How much are we talking about?With the US under Joe Biden aiming to have its electricity sector "carbon-pollution free" by 2035, the nation is already ramping up a suite of clean energy projects.

Last week US Wind Inc put in a bid to build up to 82 wind turbines off the coast of Maryland to supply the grid with an extra 1.2 gigawatts of power.

That's part of a plan to install enough wind turbines to supply the US with 30 gigawatts — enough to power 10 million American homes — by 2030.

Each wind turbine contains several hundred tonnes of materials, including anywhere between 2.4 and 6.7 tonnes of copper per megawatt, including the distribution and collector cables, according to the Copper Alliance.

Other metals in turbines include steel, aluminium and iron, as well as cobalt and rare-earths.

And those figures are just to supply a fraction of the US grid's power.

Natural resource and mining consultancy Wood Mackenzie estimated in 2019, before the Biden administration ramped up climate goals, that globally we'd need more than 5.5 million tonnes of copper to build wind turbines alone over the following 10 years.

For reference, Australia's entire annual copper exports are under 1 million tonnes.

And the amount of copper-per-megawatt in solar power plants is only marginally less than wind [power generation].

Then there are the world's cars. Scientists agree that to limit catastrophic climate change, we need to get to net-zero emissions globally by 2050 at the absolute latest — ideally, well before then.

That means a transition to 100 per cent electric vehicles.

But of the roughly 63 million cars sold worldwide in 2020, less than 5 per cent were electric.

When we start to consider all the metals involved — nickel, cobalt, lithium, rare-earths and silver among them — to build the world's electric vehicles, solar panels, smart phones, computers and batteries, the numbers start to get pretty staggering.

Will we run out?Broadly, we can think about two categories of metals: major metals that we already mine and use in large quantities, and the more niche metals, such as cobalt and rare-earths.

Major metal supply probably won't be an issue, according to Eleonore Lebre of the Sustainable Minerals Institute at the University of Queensland.

"In terms of mining, you will require much more mining of major metals because the [demand is] much higher," Dr Lebre said.

"We don't have a scarcity of [major] metals. That's not the problem."

But supply could become an issue for the more niche metals, said Richard Corkish, a solar energy researcher at UNSW.

"If we're really going to replace the world's fossil fuels, then really dramatic [niche metal] production is going to take place, much more than recently," Dr Corkish said.

He said solar technology uses a lot of silver, as well as a very niche type of low-iron sand to achieve its highly transparent glass.

"The industry is learning to use less silver, but [solar] production is expanding.

"I'm even starting to wonder about the [supply of] sands that go into the cells."

Given that renewable energy supplied just over a quarter of Australia's energy mix in 2020, Australia alone is going to have to roughly quadruple the capacity of its clean energy infrastructure (including hydro-electricity and battery storage) to get close to net-zero.

Dr Lebre said that rather than supply, she's more worried about the impact that such intensive mining will have on the environment and vulnerable societies.

"I am not really concerned about the supply itself. I'm concerned about the consequences," she said.

"At the moment, the way mining is done, they're not very good at working with local communities and what they do with the mine itself after it closes.

"That's the problem."

Where do our metals come from now?Currently, most of the world's copper comes from Chile, followed by China and Peru, according to Australian minerals exploration company Taruga.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2021-08-12/metals-technology-clean-solar-wind-batteries-phones/100338862