Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

take that to the bank .....

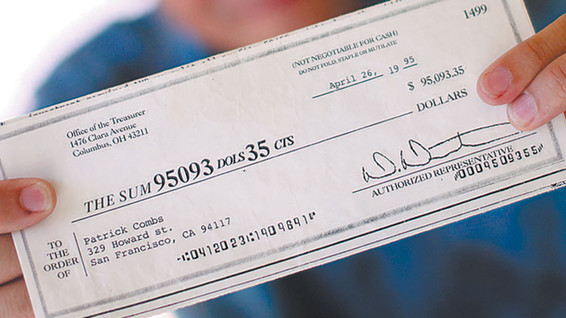

It was a cheque, made out in my name, for $95,093.35 and it came in a junk-mail letter from a get-rich-quick company. It was worthless, meant only as a financial tease, a lip-licking come-on. “This is how much money you could soon be making.” What it was never meant for was deposit. But that’s exactly what made the thought of depositing it so irresistibly funny. What could possibly be funnier than depositing a perfectly ridiculous, obviously false, fake cheque? (Did I mention it had “non-negotiable” clearly written on it?) So, as a joke, I deposited the fake cheque into my bank’s ATM. I felt like a million bucks doing so. I’d never had so much fun at my bank. Come to think of it, I’d never had any fun at my bank until the moment I endorsed the back of this “cheque” with a smiley face and slipped the Monopoly-like money into the mouth of the hungry ATM. For the first time ever, I walked away from my bank laughing.

What I expected to happen next was a short phone call from my bank. Or a letter informing me of what I already knew, that the cheque I deposited was not real. Admittedly, I also hoped for a compliment on my refined sense of humour. A “Mr Combs, what you deposited was not real but very funny, especially considering your real bank account balance history” (an account always bouncing into overdraft).

But the call or the letter never came and I forgot about my joke. Then, five days later, I returned to withdraw some cash from the ATM, and noticed a much higher than usual bank balance. $95,093.35 higher! The bank had credited my account with the fake, false, stupid cheque!

We all know it should have ended there. Fake cheque. Bank mistake. Give it back. But easier said than done. Especially considering the series of events that happened next.

The first friend I phoned informed me that it was no mistake at all. Just standard bank policy, crediting my account with the dollar amount but putting a hold on all the funds until the cheque bounced. I couldn’t touch the money and my bank balance would be embarrassing again in three days.

But seven long days later the lottery-like amount was still there and I visited the bank where an employee told me that the funds were now all available for cash withdrawal. All $95,093.35 was mine for the taking. All I had to do was ask. Windfall money begs us to take it and run. But I restrained myself. And gave the bank another two excruciatingly long weeks to do their job, catch up with their mistake, and bounce the cheque. But at the end of three hellish weeks, during which I hourly resisted the urge to take the money and run to Mexico, where it would be worth twice as much, I was told by my branch manager, “You’re safe to start spending the money, Mr Combs. A cheque cannot bounce after 10 days. You’re protected by the law.”

Now, it’s possible that any thinking man would have asked for a satchel and all the cash right then and there. Me, I must lack the gene for seizing the moment, because I didn’t touch the money. I drove myself straight to a law library to confirm for myself the 10-day rule. This triggered two discoveries. First, that my branch manager was wrong. There is no 10-day rule that protects you on a bounced cheque. It is a 24-hour rule! In the United States, when a bank receives notice that a cheque paid into your account has bounced, it has 24 hours to notify you and, if it fails to do this, you are safe to spend the money. Pretty neat, I say. Secondly, I learned that what I thought was a fake cheque was legally a real cheque. A little-known change in the 1990 Uniform Commercial Code made it so that the words “non-negotiable” printed on a cheque do not invalidate it. It may have been just a small footnote change but what I deposited was, marvellously, an accidentally real $95,093.35 cheque.

Now, I’m slow but not that slow. I withdrew a cashier’s cheque and locked it in a deposit box for safe keeping. I fully expected that the junk-mail king who had accidentally mailed out millions of real $95,000 cheques would be calling me soon, begging for his money back. I anticipated a very interesting conversation, as I’m not a big fan of get-rich-quick schemes. But what happened next was quite unexpected. My bank confiscated my ATM card. Locked me out of my account. And sent a man who I can only describe as very, very angry, to call on me.

It was interesting, not just frightening, to be yelled at by the bank’s senior security officer. Frightening because he threatened to send policemen to my doorstep if I did not immediately comply with his request for the money back. But interesting because, up until that terrifying phone call, I thought this was between me and the junk-mailer who’d sent out the accidentally real big money cheques. Until this moment in the saga, I thought my bank and I were good. Good like it said on my ATM card, “Patrick Combs, Customer in Good Standing for 12 Years.”

. . .

Politeness, courtesy and compliments on my sense of humour will get you everywhere with me. I can state with certainty that, had I received a call from the branch manager instead of the bank’s ex-military security officer and the manager had said, “Mr Combs, Patrick, may I call you Patrick? I see we made a mistake and cashed a junk-mail cheque. Our bad! May we have the money back?” I’d have returned the $95,093.35 to the bank that same afternoon. I’d have secretly hoped for free banking for a year but, no matter what, I’d have returned the dough, pronto. I’m quick to understand that everyone makes mistakes and it was, after all, just a joke. But the bank’s approach was not polite, or courteous, and neither did it take any responsibility for the mistakes the bank made, which were now piling up. Most other businesses would, I like to imagine, having realised their mistake, approached the customer in a polite, civil manner. Not the bank, they began with their attack dog, released their sharks and then later sent in their men in black (literally, not figuratively, but I’m getting ahead of the story).

So my response to the bank’s security officer was simple: “Give me a letter on official bank stationery stating that you are who you say you are, that you indeed work for the bank, and also put in that letter the reason why the bank is requesting the money back, as I’m a little confused on that. When I get that letter we’ll go from there.” And his response, to paraphrase and keep this article profanity-free, was: “Never!”

When I was a boy my mother made me write and get letters for everything. I had to write a letter to request a pocket knife from her. I had to get a letter from the man at the hardware store who said he’d hire me. I had to give a letter to the old lady across the street to apologise for the racket my friends and I had made. I emerged from my childhood with a peculiar belief in the power of the letter to make everything official. “You’re not getting any letter from the bank. Never!” were fighting words to me.

So I fought the bank for a letter and the bank fought back for the money. My stance was, “No letter taking responsibility for your mistakes, no return of the money which is legally mine.” Word of our stand-off got out and went viral on the internet, filling my inbox with emails, 99 per cent of which were from people cheering for me to stick it to the bank, the other 1 per cent from people who felt I should give back the money. The story also made the press, brought the highest legal authorities in the land on bank cheque law out of retirement, and even caught the interest of the great prankster himself, David Letterman.

Knowing I had $95,093.35 locked in a safe deposit box that I’d obtained from a junk-mail cheque but which was, by three laws, legally mine, the San Jose Mercury newspaper ran the headline: “Man 1, Bank 0.”

Of course, everyone knew that the bank wasn’t just going to forfeit the fight. Everyone sensed they’d come out swinging. The newscaster Diane Sawyer perhaps stated the public perception about banks best when she commented on my expressed desire for a pleasant resolve with the bank over lunch. She said, to all who were watching the evening news that night: “I wouldn’t count on that lunch, Patrick.”

Diane Sawyer knows what most people feel about banks. Banks don’t do business like the rest of us do business. Banks don’t do lunch to resolve an issue. They send a lawyer. Banks don’t care about your rights. They care about their rights. (Read your bank’s provided explanation of your banking rights, if you don’t believe me.) Banks don’t care about your bank balance. They care about their bank balance. And what banks really don’t do is take responsibility for their mistakes. They enforce penalties for ours.

. . .

After some thought, I decided to do a comedic one-man show telling my story around the world. In the show, I’m not ranting against banks like an angry town hall protestor but, rather, giving audiences laughs over my bank’s mistakes. I like telling a story that has a laugh at a bank’s expense.

So far the show has been a hit, with a month-long off-Broadway run in New York, and the appetite for it seems to have been fuelled by the financial crisis and a sense that the banks have screwed us over. It got another big boost last year after banks in Ireland collapsed that economy. I was able to go there largely unknown and play back-to-back countrywide tours. At one point in the show, when I would refer to a particularly fiendish Irish bank, the audience would go nuts, overjoyed that I was aware and also against the bank that had done them wrong. Patrons stood in long lines afterwards to make sure I understood just how awful Irish banks were. Some took home the book or DVD with the purpose of giving it to their banker for a lesson in manners.

Next I’m performing in Scotland, where, as I understand it, banks have also done a fine job of laying the foundation of success for me. And I see in the papers that I’ll likely soon owe Barclays a thank-you note also. Therein lies an irony. I owe despicable banks so much. Not just for the blunders that are the very basis of my show but also for the actions that have continued to create a ripe environment for my show for 10 years and counting.

At the end of the show, I reveal what, in an attempt to teach my bank a lesson in customer service, I did with the $95,000. But I don’t think that the bank did learn anything. Banks and bad behaviour, in my experience, are hardwired together. And you can take that to the bank. I did.

‘Man 1, Bank 0’ is at the Gilded Balloon Teviot in Edinburgh from August 11-26. Tel: +44 (0)131 622 6552; www.gildedballoon.co.uk

.......................................................................

Do not collect €200m

In real life, unlike in Monopoly, a “bank error in your favour” doesn’t always end favourably, writes Peter Leggatt. In April 2009 Leo Gao checked his laptop one night in Rotorua, New Zealand, and, according to his partner Kara Hurring, began “yahooing and yelling as if he was on another planet” – but wouldn’t tell her why.

In fact, a worker at New Zealand’s Westpac bank had mistakenly allocated Gao an overdraft of NZ$10m (£5.2m) rather than the NZ$100,000 he had requested. He withdrew NZ$6,782,000 in several instalments (the largest of which was NZ$2.3m), closed his failing gas station and fled to China with Hurring – although she claimed that she knew nothing of the windfall until she saw it on Chinese television.

Gao was arrested in September 2011, after two and a half years on the run, when he triggered an Interpol red alert crossing from China to Hong Kong. Hurring was arrested earlier this year when she returned to New Zealand. A trial in March found her guilty of 30 charges of theft, attempting dishonestly to use a bank card, and international money laundering. Gao will be sentenced later this month.

But lucky recipients don’t always “go directly to jail”. Last April, a businessman referred to in the German media as Michael H sold some shares for €20,000. His online bank, Comdirect, credited him with €200m instead. Having received 10,000 times the amount he was expecting, Michael H seized the moment and transferred €10m of it into his current account in a different bank.

Comdirect has since managed to regain the €200m but Michael H has been allowed to keep the €12,000 interest the money earned while it was resting in his account overnight. The bank initially demanded its return but Michael H successfully sued the bank in May.

- By John Richardson at 10 Aug 2012 - 10:10am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 19 hours ago

1 day 20 hours ago

1 day 20 hours ago

1 day 23 hours ago

2 days 1 hour ago