Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

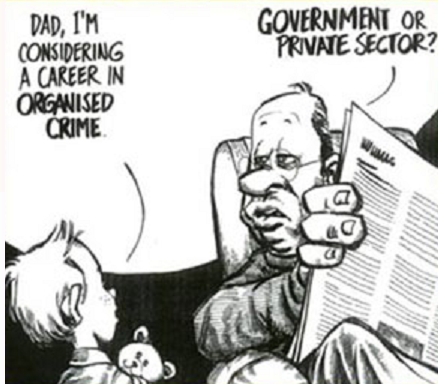

organising crime ....

Legal historian Evan Whitton says white collar criminals in England and its colonies have been a protected species since 1275.

One of our better judges, the Hon Ray Finkelstein QC, noted in an Australian Tax Office organ, Targeting Tax Crime (March 2012):

‘As a general rule the judge’s rationale in sentencing [white-collar criminals] is different from sentencing TRUE criminals … imprisonment, when available, is regarded as a last resort.‘

That need not surprise. Over the centuries, quite a number of common law judges seem to have been white collar criminals - for example, Sir Garfield Barwick.

Organised white collar crime in England dates from 1066, when William the Bastard (1027-87), became king. He franchised 90 per cent of the country to 300 “magnates” (the “great men of the realm”), and instituted a feudal system of trickle-down extortion. The magnates franchised land to freemen and extorted goods and services from them. The freemen in turn franchised land to its original owners, now peasants, and extorted from them.

His son, William II (c. 1056-1100) institutionalised white collar crime in the trade of authority. Professor John Gillingham said every public office was for sale; investors in turn extorted bribes from people who dealt with the office. He said the system was still operating in the reign of Edward I (1272-1307).

Judges and lawyers thus tended to be white collar criminals after the common law began in 1166 - you bribed the king to become a judge and then extorted from litigants. Lawyers were the natural bagmen for extorting judges.

Judging is different from lawyering, but common law judges have never been trained as judges. They are lawyers trained in sophistry - a technique of lying by false arguments, trick questions (and so on) - one day and then judges the next. Professor Alan Dershowitz said

’…lying, distortion, and other forms of intellectual dishonesty are endemic among judges.’

Justice Russell Fox said the common law was originally designed to benefit landowners, and was ‘later adjusted to the requirements of the wealthy and the powerful’. In 1275, Edward I made it a crime, Scandalum Magnatum, to accuse the magnates of vile practices, such as extortion. This form of libel law was enlarged in 1378 to protect judges, prelates and certain officials, many of whom were also white collar criminals.

Judges initially controlled evidence. On a fixed wage (plus the graft), they had no incentive to prolong the process; trials took a few hours. Lawyers do have an incentive - $5 plus a minute today - to spin the process out. The civil adversary system dates from 1460, when judges began to lawyers control civil evidence. The criminal adversary system dates from the 18th century, when lawyers first began to defend criminals.

Covering up a crime is a crime in itself - the perversion of justice. Since 1792, judges have invented five rules which hide evidence and make it difficult to charge - let alone convict - white collar and other rich criminals.

Farrer Herschell is the patron saint of organised criminals, white, blue or black collar, and other repeat offenders, including serial rapists and paedophiles. He was one of the Chancery judges who colluded with lawyers to keep a will case, Jennens v Jennens, going from 1798 to 1915 while lawyers looted the estate.

In 1894, Herschell concocted a rule against “similar facts” which conceals evidence of a pattern of criminal activity. The US has had an exception to the rule for organised crime since 1970. From 1981 to 1994, the exception imprisoned 23 Mafia bosses, and 20 extorting judges and 50 of their bagmen, lawyers and court officials. In Australia, police have been asking politicians for the exception for 29 years without success.

Lord Atkin did his bit for the rich and powerful in Inland Revenue Commissioners v Duke of Westminster (1936). He ruled:

‘ … the subject, whether poor and humble, or wealthy and noble, has the legal right to so dispose of his capital and income as to attract upon himself the least amount of tax.’

Poor and humble wage and salary earners cannot evade tax; it is deducted at source.

Section 260 of the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 barred “absolutely” any attempt, “directly or indirectly”, which would have the effect of “evading or avoiding” the “duty” to pay tax.

Sir Garfield Barwick, a tax lawyer, argued in Keighery v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (High Court, 1957), that “absolutely’” does not mean “absolutely”; there could be exceptions. Five judges agreed: Sir Owen Dixon, Sir Dudley Williams, Sir Eddie McTiernan, Sir Frank Kitto, and Sir Alan Taylor. That opened the tax evasion floodgates.

Barwick was Chief Justice from 1964 to 1981. In that period, he evaded tax, was entitled to two years’ in prison for not disclosing his interest in companies before the court; and in a series of tax cases from 1970 to 1978 effectively stole $10 billion (at today’s rates) from the Tax Office.

Curran v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1974) was a monument of sophistry: Barwick, Sir Harry Gibbs, and Sir Douglas Menzies argued that a profit of $2,782 was a loss, for tax purposes, of $186,046.

Over the past eight centuries, it does seem that any number of common law judges have been white collar criminals. However, we have to remember that it is necessary to prove a wrongful mind (mens rea) as well as a wrongful act (actus reus).

Odd as it may seem in at least some cases, judges may lack a guilty mind because, for 200 years, law schools have taught students that the adversary system is the best, and that it requires practitioners to do these terrible things.

Anything can be rationalised.

Or, as Professor Bent Flyvbjerg said:

‘Power often finds deception, self-deception, lies, and rationalisations more useful for its purposes than truth and rationality, [but that] does not necessarily imply dishonesty. It is not unusual to find individuals, organizations, and whole societies actually believing their own rationalisations.’

- By John Richardson at 14 Nov 2012 - 5:44pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

9 hours 33 min ago

9 hours 40 min ago

9 hours 50 min ago

9 hours 54 min ago

9 hours 58 min ago

10 hours 1 min ago

10 hours 12 min ago

11 hours 9 min ago

13 hours 8 min ago

13 hours 57 min ago