Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

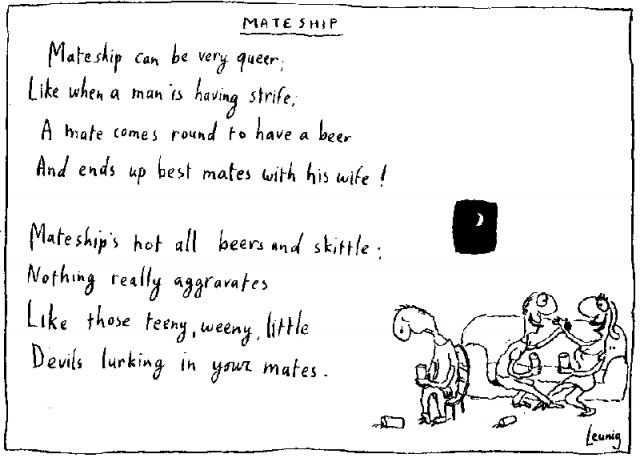

mmmmmaaaaaatttteee .....

I picked James, age three-and-a-half, up after his first day at preschool in Massachusetts, where we had lately gone to live for a few years.

“How was it, mate?” I asked, knowing already from the look on his face that it had been okay, but that he also was glad to see me after his half-day among these new people with their funny accents.

“Goo-ood,” he said, in a tone somewhere between brave and enthusiastic.

A minute later, though, I heard real enthusiasm, in the disembodied voice of his teacher, emanating from the window as James and I headed down the steps outside the staffroom.

“Did you hear that?” she gushed to her colleague.

“He called him mate. How cuuute!”

Silly as it seems, it brought on a little feeling of expatriate pride, a brief happiness attack, to hear this little Australian word of affection so celebrated.

But it should be celebrated for, as far as I know, no other English-speaking country has a word so usefully flexible for referring to ones fellow humans. Certainly the United States doesn’t have an equivalent all-purpose word.

An American parent, for example, might use “buddy” when greeting his kid as I greeted James. But in almost any business interaction it would be more formal.

It would be “sir” or “ma’am”. It would be “Mr Seccombe”, seldom “Mike”.

More on this in a minute, for it goes to the heart of my objection to the ridiculous directive issued to health workers on the New South Wales north coast that they must not call colleagues or patients “mate”.

But first, let’s go to some other attributes of the word.

It’s very useful, for a start, for people like me who are bad with names.

It is egalitarian, at least in this country. Just about anyone can call just about anyone else mate, regardless of social status. Watch the prime minister out on the hustings, greeting the public with an extended hand and a sunny “gedday mate”, and getting the same in return.

You wouldn’t see that in America. An English friend tells me you wouldn’t see it in Britain either, where the term still has class connotations. David Cameron would not call Rebekah Brooks mate. And, says my friend, such a toff would sound pretty silly even if he referred to a working man as mate.

In this country mate is most commonly a term of endearment, traditionally among men, but pleasingly now often used by and to women.

Yet also on occasions it can signify aggression, as in “You want a go, mate?”

It can serve as an intensifier as in “Mate, is it hot or what?”

Or it can simply be a one-syllable exclamation, as in “Maaaaate!”

But let’s get back to the central argument here, which is that it is a dumb idea to forbid those health workers from calling their patients or even their co-workers “mate”.

The directive asserted a need for professional language within the workplace at all times. It specified a number of terms which were not to be used, including “darling”, “sweetheart” and “honey”, as well as mate.

“The utilisation of this language within the workplace at any time is not appropriate and may be perceived as disrespectful, disempowering and non-professional,” it said.

“This type of language should not be used across any level of the organisation such as employee to employee or employee to client.”

A couple of observations on this memo.

First, the word “utilisation” also should be banned.

Second, the memo probably had a point about those other words – although context matters. It is one thing if a woman member of staff uses them to calm a distressed child, and quite another if a younger male member of staff uses them towards a female patient.

But mate? So long as it is not used aggressively, as in “look here, mate…” I think it should be encouraged.

It’s personal. It’s comforting.

Who cares if, strictly speaking, it is not professional.

As it happens, I was in hospital only a few hours before writing this (nothing major, don’t worry yourselves), and I can tell you, it feels good when an orderly, nurse or doctor, speaks to you personally, not simply professionally.

Like I was saying before, I used to live in America, where they don’t call you mate, but “sir”.

On the face of it, that sounds more respectful, but experience taught me it is not necessarily so. In fact what this formality does is set boundaries.

It says: “You are the customer and I am paid to assist you, in so far as my customer service handbook allows. But this is a professional transaction, so let’s not pretend we have any human relationship.”

Now I don’t want to go all jingoistic and John Howard-like with a treatise on mateship, but I really do think the way we use the word mate is a powerful signifier of Australia’s national character.

It’s like my other favourite Australianism, “no worries”.

To me it signals empathy in a ready-to-oblige, egalitarian, no-fuss sort of way.

And some bloody bureaucrat who uses words like “utilisation” now wants to ban it?

I mean, maaate!

- By John Richardson at 13 Dec 2012 - 6:40am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

3 hours 36 min ago

6 hours 32 min ago

8 hours 51 min ago

18 hours 31 min ago

19 hours 20 min ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 5 hours ago

1 day 7 hours ago

1 day 8 hours ago

1 day 8 hours ago