Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the high roller .....

He ditched his father’s media empire, lost a fortune in Vegas and used gaming to get his financial strength back. Now a slimmed-down, cashed-up James Packer is showing his muscle, powering his casino plan into Sydney Harbour’s last prime real estate site.

Not one, but two tall cranes have been towering over a construction site in the upmarket Sydney harbourside suburb of Vaucluse, where the new Packer compound is rapidly taking shape. Dominating this hillside site is a 1970s mansion with a modernist colonnade seemingly modelled on the stark lines of a de Chirico abstract — it could be the official residence of a Latin American potentate. The new additions to the site have more of a corporate sheen, as if their glass, concrete and steel facades had been inspired by one of James Packer’s casinos in Melbourne or Macau. The Crown logo would not look out of place here.

With its 23-metre indoor pool, underground cinema and 13-car garage, the compound certainly has a high-roller aesthetic. The garage alone is bigger than most Vaucluse residences; Packer bought two such properties for a reported combined cost of $10.3 million, only to demolish them in order to increase the dimensions of his plot. Not only has it been an exorbitantly costly construction project but also an enormously challenging one. To excavate the cavernous underground space, the main mansion had, for a time, to be virtually suspended in the air.

As it continues to take shape, the residence might be seen as a totem of filial one-upmanship from a cowed son who has struggled to escape from the shadow of his domineering father, Kerry Packer. Unquestionably, James’ new home will be far more swish than the nearby Bellevue Hill pile that his grandfather, Sir Frank Packer, bought for just £8,000 during the Depression, and which Kerry kept enlarging by colonising neighbouring properties. For James Packer, the switch from his Bondi penthouse apartment to the more refined climes of blue-blood Vaucluse is a sign of his rising seniority within the Australian business community. Maybe that’s why the colonnade caught his eye: it is an architectural rendering of power as well as opulence.

But it’s the view from his new $43 million home that Packer might eventually come to most savour. Among the best that Sydney has to offer, it takes in almost the entire expanse of the harbour and the jagged skyline of the city centre, along with the coat hanger of the Harbour Bridge and the shells of the Opera House. For the 45-year-old gaming magnate this panorama is yet incomplete. To the city’s two most famous landmarks, he wants to add a third. If things go to plan — and right now they are proceeding pretty much as he would have scripted — he will be able to look out from his terrace to a new, 60-storey hotel at Barangaroo, on the northern arm of Darling Harbour. Its uppermost floors will house a VIP casino, with more than 150 gaming tables, which will attract rich Asian gamblers, or “whales” as they are known in the trade. In Packer’s mind’s eye, it will be the Crown in Sydney’s jewel.

At the start of 2012, a Crown casino at Barangaroo, on the blue-ribbon waterfront site once occupied by a cruise-liner passenger terminal, was not on the public horizon, even though Packer is thought to have been eyeing the site since 2010. By year’s end, it had become almost a fait accompli. What Packer predicts will be the world’s premium six-star hotel has now not merely been welcomed by the New South Wales government, but also fast-tracked under new measures allowing prestige projects to bypass normal planning procedures. On what was already Sydney’s most hotly contested patch of undeveloped real estate, Packer has been given the planning equivalent of a “green corridor” — the kind of traffic-light-free passage, with outrider escort, otherwise conferred upon only visiting heads of state. That is, the casino will not be subject to a tender process, nor will community consultation be required, despite the fact that Barangaroo is public land and the only significant harbourside site that has not yet been developed.

As Sydneysiders know all too well, the site has rarely been off the front pages in recent years. In 2010, it was the controversy surrounding an early iteration of the masterplan: to build a skyscraper designed by the British “starchitect” Richard Rogers on a pier jutting 150 metres into the harbour. The following year, it was Paul Keating’s pyrotechnic resignation as chairman of the Design Excellence Review Panel overseeing the Barangaroo site, after he’d had a row with the Sydney lord mayor Clover Moore. The former prime minister described Moore as having a “miserable, microscopic view of the world”, adding that she stood for “sandal-wearing, muesli-chewing, bike-riding pedestrians”. Now, it is Packer’s ambition for the site that has grabbed the headlines.

The Premier Barry O’Farrell, who describes Packer admiringly as “shrewd and successful”, has become a backer for the project. This, despite campaigning during the 2011 state election on a platform of bringing greater transparency to the state’s planning process and an end to precisely the kind of backroom deal Packer is now enjoying. “I think it’s an exciting proposal which could add extra life to Barangaroo, give Sydney another world-class hotel, generate jobs and boost tourism,” O’Farrell gushed last February.

Keating, whose imprimatur is so important because of his close personal association with the site, also signaled his approval after meeting Packer last year, so long as the project did not encroach on the land earmarked for public parkland. Crown could build “a hotel of world rank”, he noted in a written statement, adding that VIP gaming offered the only means of funding the building. Keating even suggested that the new tower should ideally resemble “a Brancusi sculpture’’, and become the diva of the site. Packer was evidently delighted. Hearing Keating muse about architecture, he joked afterwards, was “like listening to someone reading Fifty Shades of Grey”.

So, in the State Parliament, what you would expect to have been a highly contentious project has come to enjoy near universal support. Labor, after receiving assurances that the hotel would be restricted to only high rollers and not operate poker machines, has been as enthusiastic about the project as O’Farrell. Labor’s spokesman for planning, Luke Foley, after meeting Packer in August, agreed that Sydney needs a six-star hotel, and that VIP gambling would make it commercially viable.

Packer has personally conducted much of the lobbying effort for his vision of Barangaroo. Recently, for instance, when The Australian newspaper’s Imre Salusinszky found himself in the lift with Packer at Parliament House, the state political reporter naturally asked whether he was there to see the Premier. “No. John Robertson,” replied Packer, referring to the Labor Opposition Leader. In lining up Labor support, Packer has been assisted by two one-time NSW powerbrokers, who are now on the Packer payroll: Karl Bitar, the former national secretary of the party, and the well-connected Mark Arbib, the former federal sports minister, who took up a position with Crown after retiring from politics last February. Bitar and Arbib have assumed much the same role that the Keating-era powerbrokers Graham Richardson and Peter Barron performed for Kerry Packer. Arbib was present at the meeting with Luke Foley, for instance. They have also been central in bringing on board the hospitality workers’ union, United Voice.

The union was even persuaded to agree to smoking in the gaming rooms, a policy u-turn from officials who have campaigned for a complete ban in other casinos and had only recently complained that the NSW government had been gambling with the health of casino workers.

The union, which says Crown has offered its members more verifiable protections on smoking than Star Casino, has been promised an office in the new development that is bigger than the broom cupboard it presently has in Sydney’s existing casino.

To broaden the support base even further, Packer has won the support of community organisations such as the National Centre of Indigenous Excellence. A long-time supporter of initiatives aimed at indigenous advancement through enhanced employment opportunities — an approach he shares with his close friend Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest — Packer has promised to train more than 2,000 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders to work at his new hotel.

Back in the day, Kerry Packer leveraged his media holdings to make politicians more malleable. Indeed, it was James who famously warned a minister in John Fahey’s NSW government that it would be “fucked” if it did not back his father’s 1994 bid for the Sydney casino licence. Nowadays, however, he does not have Channel Nine or The Bulletin at his beck and call. So, lacking the fear factor his father engendered, he has come to rely on carrots rather than sticks. In pushing the Barangaroo development, he played up the fact that casinos — or “integrated resorts” as he prefers to call them, to avoid using the controversial c-word — offer state governments billions in tax revenues and the promise of thousands of jobs. He has two Crown casinos in Australia to cite as examples: in its 18 years of operation, Melbourne’s Crown casino has directly contributed more than $3 billion to the Victorian Treasury; then there is the cascade effect on the state economy of the 18 million visitors it claims to attract annually, a large proportion from Asia. In Perth, Packer’s Burswood casino complex has a workforce of 5,600, making Crown the largest single-site employer in Western Australia.

From the still embryonic Sydney casino, Crown estimates the NSW government will receive annual tax revenues of $114 million. In addition, it will provide 1,300 jobs during the construction phase, and 1,200 positions when it becomes operational. So confident has Packer become in the persuasiveness of his economic case, and the efficiency of his lobbying machine, that he has publicly vowed never to invest in a city where his projects do not enjoy bipartisan support, as they have in Melbourne and Perth. And Sydney has also happily complied.

Presently, NSW operates a one-casino policy, with the solitary licence, held by the Star casino, not due to expire until November, 2019. The Star, a complex across the water from Barangaroo, is owned by Echo Entertainment — a casino group with premises on the Gold Coast and in Brisbane — which Packer had targeted for takeover. Last year, he not only sought to increase his stake in the group to 25 per cent, but also launched a campaign, backed by aggressive full-page press advertisements calling for the resignation of Echo’s chairman, John Story, who stepped down in June.

Now that Packer has lined up so much political support for his new casino, however, his plans to take over Echo Entertainment are no longer so urgent. What makes bipartisan support from NSW political parties so critical is that it opens the way for new legislation that would allow a second casino licence. To that green corridor, then, the NSW political establishment has added a red carpet, with senior Liberal and Labor figures performing the roles of eager doormen. Last weekend, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the chief executive of Crown, Rowen Craigie, was allowed to re-write a press release announcing the NSW government’s initial backing for the project before it was issued by O’Farrell’s office. It has also refused to publish a report it commissioned from Deloitte to assess the economic benefits of the scheme.

“He’s played an absolute fucking blinder,” says a leading businessman, who has known Packer for years, and not always been impressed by him. “Think how ballsy you have to be to say ‘Change the rules and give me a second casino licence’. But that’s what’s happened, even if it’s made Australia look like a low-rent South American state. It’s not the front of a barn door. It’s the front of a door the size of an aircraft hanger.” It is as if Australia has regressed, he adds: “We’ve returned to the divine right of kings.”

Up against the casino’s coalition of the willing are the Greens and independent MP Alex Greenwich who campaigned against the project in the Sydney by-election last October. However, they are helpless to stop the project, because of their insignificant parliamentary numbers. “If you are asking whether we are impotent,” laments Greens MP John Kaye, “then the answer is yes”. In November, Kaye tried to have the state government’s handling of the casino project referred to the Independent Commission Against Corruption. As he wrote to the commissioner, the O’Farrell government had failed “to provide an adequate explanation for weakening requirements for a private proposal to be subject to a competitive tendering process”. But this gambit was a complete non-starter.

“In the 1980s, short cuts were expected,” says the anti-casinos campaigner Tim Costello. “I thought we were beyond that.” But, he says, when it comes to, “those who are rich enough, politicians are dancing to whatever they say. No debate, no tender, no public consultation is very shabby”.

“We’re locked out. The deal is sown up. This is a very NSW process,” Costello says. “It’s been rotten since the Rum Rebellion.” There are leading figures in the Sydney business community who agree. “It’s Louisiana or Mississippi,” says one.

Seemingly the only option for Packer’s opponents is to mobilise public opinion against him. “I’ve been amazed at how small the outcry has been in terms of official groups,” Kaye says, “but how strong the response has been in letters to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald. He’s picked off all the organisational stakeholders but not the people of Sydney.”

To protect this flank, Packer has invested heavily over the past year in building up the Crown name, not just as a “global luxury brand” — his new three-word mission statement — but also as a power for social and economic good. Full-page advertisements in The Australian, The Australian Financial Review, the Herald Sun, and The Daily Telegraph have spruiked the economic dividends of the Barangaroo project. Television viewers have grown used to the ubiquitous sight of a top-hatted Crown doorman wandering from room to room extolling the virtues of an industry that many have come to associate with vice. With glitzy production values, and a script that omits the word “gambling”, the ads are reminiscent of the anti-mining-tax campaign run by the resources sector, another industry that must contend with NIMBY-ism and a poor public image. Rather than being formulated to entice potential customers into casinos, the ad campaign spruiking Crown was aimed squarely at building brand awareness.

Although the top-hatted doorman has become Crown’s main on-air brand ambassador, the chairman of the company has also emerged from his former media-shy corner, into which he seemed to retreat, punch-drunk, during the global financial crisis. Over the past 12 months, Packer has granted reporters access. And his reward for facing the cameras with carefully selected reporters such as Channel Nine’s Karl Stefanovic (who was a guest at Packer’s wedding to model Erica Baxter on the French Riviera in 2007) has been coverage bordering on the fawning. A 60 Minutes profile felt like a Barangaroo infomercial, and ended with the soft-ball question: if Kerry were still alive “would he be punting in your casino”?

“Mate, if he was here,” guffawed James, “it wouldn’t be my casino, it would be his.”

If, in the interview with 60 Minutes, he still looked rather uncomfortable under the hot klieg lights, when it came to being interviewed on camera by a reporter from The Australian in Perth, he was positively lugubrious. During this media opportunity, he outlined his plans for Burswood and heaped praise on the state premiers who have either lent support to his ventures or might do so in the future (O’Farrell he said was “terrific’’, Queensland’s Campbell Newman was deemed “a real go-getter”, while Colin Barnett of Western Australia was up there with his close friend Jeff Kennett, the former premier of Victoria). For a man who for years was so ill at ease with the media, Packer was suddenly uncharacteristically self-assured.

The same confident air was evident last October when he agreed to a chat-show-style question-and-answer session at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, which was sponsored by The Australian Financial Review. He was expansive, occasionally witty, candid and self-deprecating. “No one’s made more mistakes than I have,” he said at one point, referring to his patchy business career, “but I keep going”. With his mother Ros, sister Gretel, and wife Erica in the audience he also paid warm tribute to his father, who used gambling in his later years to get the kind of adrenaline rushes that big business deals had once provided. “My dad was a lot smarter than I am, and a lot more successful than I’ll ever be.” There was also a stout defence of the gaming industry. “You’re selling adrenaline, and they’re [the customers] happy to pay for that. It’s a fun business, as long as you’re not hurting people.” The AFR, like those clapping in the audience, seemingly lapped it up, and headlined its report of the evening: “James Packer, his father’s son, and then some”.

An AFR front-page story on the Burswood upgrade was also overwhelmingly positive. It was illustrated with a picture showing a smiling Packer with his feet up on the desk and his smart phone at the ready. It looked as if he had just won big on the blackjack tables, and was texting his friends to share the happy news. The photo was captioned: “James Packer: ‘I want to create a global luxury brand.’” Packer also appeared on the cover of the AFR Magazine last month in an article, “How the richest of the rich are changing the world”, which was the puffiest piece to date. In fact, Packer is close to fulfilling the same role for the AFR that Shane Warne’s fiancée Elizabeth Hurley once performed for the British broadsheet The Daily Telegraph, a newspaper which the satirical magazine Private Eye took to calling the “Hurleygraph”.

The Sydney Morning Herald has been more sceptical. Its state political reporter Sean Nicholls has done especially well at revealing Packer’s lobbying efforts, from the meeting with Luke Foley at Packer’s Park Street headquarters to the hospitality bestowed on Mark Boyd, the NSW state secretary of United Voice, who was entertained by Mark Arbib at last year’s AFL grand final. Still, in November the Herald opened up space in the news pages for an opinion piece by Packer, which it billed as an “exclusive” and published under the headline: “For the good of Sydney, back this plan”. In it, Packer sought to rev the competitive instincts of Sydneysiders, who have watched Melbourne outstrip the Emerald City since the 2000 Olympics. “Crown is committed to giving Sydney an iconic project,” he wrote, “that can give our city back the spark it had a decade ago.”

For much of the past six months, from Australia’s leading business paper in particular, Packer has received the kind of beneficent coverage that would no doubt please his firm friend Gina Rinehart, who in recent weeks appears to have revived her takeover plans for the Fairfax Media group. In fact, had it not been for Packer, Rinehart might never have embarked on her media spending spree in the first place. Gina watchers believe that an emotional speech delivered by James at a tribute event for Alan Jones in November 2010 was pivotal to her media ambitions. Packer, a great admirer of the right-wing broadcaster, welled up as he recalled the advice his father had once given Jones. “What do you want to be, son? The prime minister or a millionaire?’’ Rinehart apparently greatly enjoyed the speech, and afterwards wrote Packer a letter of congratulation. He had recently bought an 18 per cent share in Channel Ten, which he has since offloaded, and his investment may well have been the spur. Days later, Rinehart bought a 10 per cent share of Ten, where soon after they became boardroom buddies.

Perhaps as a result of the obsequious press coverage, Packer has become much more comfortable with reporters whom he once considered hostile. Ros Reines, The Telegraph’s gossip columnist and self-styled “Tabloid Terror’’, is a case in point. In 2001, at a Channel Nine season launch party on Sydney’s Garden Island, Packer subjected her to a vicious carpeting, which she likened to an encounter with “a wild beast”. Packer had taken offence at one of her columns and summoned her over to deliver his dressing down. “He kept on shouting I was bullshitting him,” recalls Raines, who described the party-stopping encounter as like an out-of-body experience. For years she steered well clear, fearing another nasty public scene, but Packer eventually signaled he was ready for a rapprochement when he accepted an invitation from Neil Breen, the then editor of The Telegraph, to send Reines a jokey goodwill message for her 60th birthday last September. A couple of months later, at a function held at Crown casino’s Club 23 poker emporium on the eve of Derby Day, Reines was again summoned by Packer. At first she thought: “Oh fuck, here we go again.” But this time, having just taken his wife for a spin on the dance floor, he was in a convivial mood. “He said, ‘I hear that you’re human,’” she remembers, to which she replied in the affirmative. Then he playfully admonished her. “You’ve written a million bad things about me,” she remembers him saying.

“Not a million,” she retorted.

“Yes, a million,” he apparently replied. Then, theatrically, he kissed her hand. “He’s created this new persona,” reckons Reines, who has been watching Packer, close-up and from a safe distance, for a decade. “The wife, the kids, the new boat, the new mansion. He’s finally comfortable in his own skin.”

If Rinehart, one of the resources magnates who ousted him from his perch as Australia’s richest person, dominated business news coverage during the first half of last year, James Packer came to be the central personality at its tail end. But there’s a key difference in the tone of their media dominance. That is, Rinehart has largely been the subject of a scornful press, even among Fairfax publications, the group that she now partly owns. The narrative that has attached itself to Packer is of the Comeback Kid, who now rivals his father.

Regulars along the cliff-top path that links to Bondi and Bronte beaches in Sydney’s eastern suburbs have grown used in recent months to seeing a figure at once familiar and unrecognisable: the new, slimline Packer. He runs alone at a deliberate, if somewhat shuffling pace, dressed in torso-hugging Lycra that shows off his remodelled physique. Since undergoing gastric bypass surgery at a Los Angeles clinic just over a year ago, he has reportedly shed more than 40kg. Reaching 90kg is said to have been his target, an achievement he celebrated by emerging, Daniel Craig-like, from the surf at Bondi, much to the telephoto delight of a waiting paparazzo.

For a billionaire whose self-esteem seems to be linked almost as much to his weight as his wealth, his waistline is a key indicator of his business confidence. Losing weight, evidently, makes him feel a more substantial figure. So although there are rumours that he plans to relocate his family for six months to Argentina, which has become a fashionable place for the global super-rich to ride out the global downturn, long-time Packer watchers expect him to stay. Notes one: “When things are going well, he tends to stay in Australia.”

During the depths of the global financial crisis, as the share markets tumbled, and when his biographer Paul Barry reckoned he was haemorrhaging $480,000 an hour, Packer’s physique was especially corpulent. As his estimated net worth of $6.2 billion slumped by two-thirds, friends also confided that he was deeply depressed. Back then, profiles of Packer read like a case study of a third-generation screw-up. Following the death of his father on Boxing Day 2005, he had embarked on an extravagant spending splurge, splashing out on a $50 million yacht to expand the Packer armada and also buying a $60 million corporate jet to modernise its air fleet. More controversial was his decision to sell Channel Nine, the centrepiece of his father’s business empire, and also other media interests that the Packers had spent more than 80 years slowly building up. His decision to ditch media and direct the family business towards gaming was seen not only as highly risky but also as a betrayal of his father’s legacy.

But gaming was a business that Packer learned from watching his father in casinos, and it was he who had persuaded Kerry to make the family’s first successful venture into the casino industry. “I thought ‘Fuck, this must be a good business’,’’ he told the crowd at the Museum of Contemporary Art in October. In 1999, then, at the behest of his only son, Kerry took over the Melbourne casino, which had been opened by the businessman Lloyd Williams on the city’s South Bank five years earlier. Now, with a licence for 500 table games and 2,500 pokies, it is the largest casino in the southern hemisphere, offering gambling on an almost industrial scale. “James showed his independent streak,” says the former Victorian premier Jeff Kennett, a friend to both father and son. “He convinced his father to buy Crown. It was only James’ continual bidding that convinced his father to buy. That was when James started to flourish.”

Gambling, however, also almost brought about the younger Packer’s downfall, when his ambition of becoming a major player in its global capital went the way of so many Las Vegas dreams: with a haemorrhage of cash. Packer sought to expand his American holdings at the top of the market, just as the city was about to be hit by “Hurricane GFC”. In 2009, he lost USD250 million when a project by Fontainebleau Resorts, to build a 63-storey casino at the rundown northern end of the Las Vegas strip, went bust. A USD242 million investment in Station Casinos, another Las Vegas gaming company, also had to be written off. Gambling lore has it that Kerry Packer once won more than $9 million at the Las Vegas Hilton, betting $150,000 on each hand (in celebrating this win, he apparently rewarded a lounge singer with a $100,000 tip). For his son, Sin City mainly brought financial pain, and James now concedes that he should have anticipated how the sub-prime mortgage crisis would spill over from America’s suburbs into its gaming houses. Publicly, he has admitted the Las Vegas episode is his worst business decision to date.

The failed investments also reinforced the public perception, first formed when he lost $400 million of the family fortune in the telecommunications giant One.Tel, that he was cursed with the opposite of the Midas touch. Now the stuff of Australian tall-poppy folklore is his business partner Lachlan Murdoch’s testimony before the NSW Supreme Court; he remembered a meeting in the kitchen of his home, in which Packer had broken down in tears and blubbed, “I’m sorry”. By squandering so much money, both mini-moguls were deemed to have badly let down their fathers.

At the same time One.Tel was imploding, Packer’s first marriage was also collapsing. In 1999, he had wed the swimwear model Jodhi Meares in a lavish ceremony at his father’s Bellevue Hill mansion. In what Ros Packer described as the wedding of the century, 750 guests heard Elton John serenade the newlyweds, and James’ Channel Nine mate Eddie McGuire served as MC. According to Packer’s friends, Jodhi had been attracted to James’ vulnerability, and around her he often lapsed into what they describe as a “baby voice”. She struggled, however, with the downsides of marrying into what was then Australia’s richest family, not least the endless tabloid scrutiny. The couple split in 2002, although they remain on close terms and, I am told, speak regularly.

The combined effect of his professional and personal woes led Packer to “the very edge of a nervous breakdown”, writes Paul Barry. Solace came in the form of membership of the Church of Scientology, to which Packer’s friend, the movie star Tom Cruise, had introduced him. Whether it was reading church pamphlets or the teachings of founder, L. Ron Hubbard, spending an hour or so every couple of days practicing Scientology helped him get a “better outlook on life”, Packer told the AFR in 2006. Once reckoned to be Scientology’s most wealthy advocate, he has since distanced himself from the organisation. Hubbard was, after all, an outspoken critic of gambling. Those who have observed him over the years say that the newly emboldened Packer no longer requires such a crutch.

Packer took his second wedding, this time to Erica Baxter, offshore. The guest list included Rupert Murdoch and Wendi Deng, Lachlan and Sarah Murdoch, Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes, his childhood friend the Channel Nine boss David Gyngell, Eddie McGuire and Alan Jones, and the celebration reportedly cost some $6 million. This, despite James’ noting beforehand that the nuptials would be “nothing lavish’’.

The following year, in 2008, the global financial crisis hit.

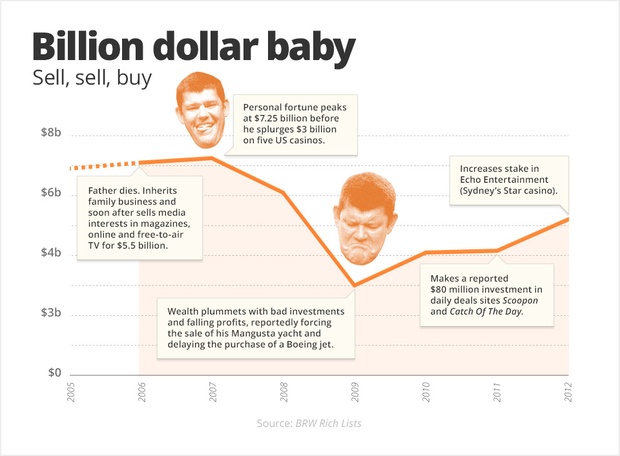

Now, though, Packer has begun to recoup much of the money he lost — sums which include an estimated $3 billion in 2009 alone. The 2012 BRW Rich List put his net fortune at $5.2 billion, a rise of more than $1 billion on the year before. It places him sixth, behind the likes of Gina Rinehart, Frank Lowy, Andrew Forrest and Anthony Pratt, but ahead of Clive Palmer and Kerry Stokes. In hindsight, offloading Channel Nine and ACP Magazines to the venture capital firm CVC Asia Pacific — at the top of the market — seems to have been a masterstroke. Between 2006 and 2008, the sale raked in $5.6 billion. His joint casino venture in Macau has also performed well, helping Crown achieve a net profit of more than $513 million last year, a 53 per cent rise on the previous year. In what was widely viewed as another good deal, Packer recently sold his last serious media holding, a 50 per cent stake in pay TV group Consolidated Media Holdings, to News Ltd for $2 billion.

Friends of the Packer family also say that his personal life is on a much surer footing. His marriage to Baxter is said to be solid. The couple have three children, Indigo, 4, Jackson Lloyd, 2, and one-year-old Emmanuelle Sheelagh. “He’s become a man with a destiny, and decided what he wants to do,” says one friend. That is, he intends to, “Build an empire, get well and be a good husband and father.”

Along with his wealth, his stature within the business community has also grown. His early investments in digital media, most conspicuously in the online jobs website Seek, are now seen as prescient (in 2003, he bought 25 per cent of Seek for about $33 million, and sold it six years later for just over $440 million). Packer sees these early digital moves as his most notable business achievement so far, not least because he spotted the Internet’s vast potential. The rise of the Chinese middle class, he reckons, will be even more transformative. “I think it may be even a bigger story than the Internet,” he told 60 Minutes. “The Chinese middle class is going to change the world.”

This Chinese demographic is, without doubt, going to transform tourism in the Asia Pacific, and, according to Kennett, Packer was the first in Australia to recognise how premium casinos could draw the affluent Chinese to our shores. So does that make him an Australian visionary? “That’s going over the top,” Kennett says. “He’s proved himself to be very astute to recognise the long-term value of gaming.” Kennett has also seen Packer mature into a formidable executive. “James is very good at numbers, and he has an ability to make decisions quickly,” he says. “He has a great eye for detail and a willingness to take considered risks. He’s made some mistakes, but he’s learnt from them.” Kennett characterises Packer’s move away from media into gaming as “bold and courageous’’. Other leading Australian businessmen concur that Packer’s business smarts are often underestimated. Kim Williams, the head of News Ltd, has called him “strikingly brilliant, possibly the most numerate person I’ve ever met”.

One leading businessman believes that Packer’s newfound confidence stems partly from the solidness of his gaming business model. “He’s had a couple of near-death financial experiences,” says one, “but he’s got a really solid fortune and a really good business. All he has to do is chip and putt rather than swing for the fences.” In terms of his self-esteem, it helps that Packer has outstripped his long-time friend and fellow scion Lachlan Murdoch: “He’s proved himself to be a better businessman than Lachlan,” the friend adds.

Still, there are senior figures in the Sydney business community, unprepared to go on the record, who view Packer in a wholly different light. They see his sudden weight loss, not as signaling fitness and wellbeing, but rather as a sign of his volatility. The fluctuations in his waistline are like his mood swings, they say.

Nonetheless, his public appearances suggest that just as his skin now has a better fit, so the dynastic burden that weighed so heavily during earlier phases of his career seems to be much lighter. “Dad was an amazing man,” Packer said at the Museum of Contemporary Art, one of many tributes he made that night to his father. “He had a capacity to keep going and to be very determined about things when he needed to be. That was a real lesson.” Here, perhaps, Packer was recalling the father who thought nothing of kissing his grown-up son in front of colleagues at the family’s corporate headquarters on Sydney’s Park Street, rather than the tyrant who, in James’ teenage years subjected him to the backyard barrage of a bowling machine that fired cricket balls at 190km/h. When a sympathetic coach tried to turn it down a notch to 160km/h, still a faster clip than Jeff Thomson and Dennis Lillee could have pitched when in their prime, Packer senior reportedly exploded. “What are you trying to do,” he shouted, “turn him into a wuss or what? Come on, he’s a man! Turn it up a bit!”

Still, the father-son relationship remains a touchy issue. When Paul Barry’s 2009 biography quoted an unnamed friend suggesting James came to hate his father and felt an “enormous release” following his death, Andrew Forrest, Gerry Harvey, Kim Williams, Alan Jones, Eddie McGuire and the investment banker Matthew Grounds were so quick to publicly reject the claim that it felt as if the response had been co-ordinated. “I don’t think he wants to ever emerge from his father’s shadow,” Kennett says. “To say that he’s emerged from his father’s influence is something he would reject. He is his father’s son.”

In recent times, there have also been brief public glimpses of a manner that Packer watchers would recognise as more Kerry than James. He has, on occasion, almost ventriloquised his bad-tempered father. The most well-reported episode is his spray at David Leckie, the former Nine Network executive who went on to run Channel Seven, at a party at the Sydney Opera House to celebrate his fellow media executive Sam Chisholm’s 70th birthday in October 2009. “I am here to tell you my father was right,” he said, wagging his finger at a speechless Leckie. “You are a raging fuckwit. Now fuck off.”

Like Kerry, James has also started to pontificate on the issues of the day, though he has stopped well short of the kind of billionaire activism favoured by the likes of Rinehart, Forrest and Palmer. The rise of China, and the commercial potential for Australia, has become something of a pet subject. “If you’re a mid-ranking power in the world, what you try and do is make friends,” he told the AFR forum. “Once you’ve got friendships it’s easier to have proper conversations about difficult subjects. I think the view from China is Australia does not try hard enough to attract their business and to integrate with Asia Pacific. It is incumbent upon our political leaders to spend more time in that part of the world.” Much of it is boilerplate analysis, but Packer now clearly feels it incumbent upon him that he lend his voice to the national debate, especially when it touches on his commercial interests.

All this comes at a time when the currency of the Packer family name has increased in value. Channel Nine’s Howzat!, the story of World Series Cricket built around a sympathetic portrayal of Kerry Packer, became one of the surprise television hits of 2012.

But whereas the Packer cricket revolution is viewed almost universally as a positive enhancement of Australian life, James’ gambling revolution is seen as a much more destructive force.

With the aim of constructing a skyscraper that will not merely complement Sydney’s two great icons, but rival them, Packer has promised to hold an international design competition for his new hotel casino. Constructing “an absolutely spectacular building” is his aim.

The aesthetics of the waterfront Crown complex in Melbourne, which occupies 510,000 square metres of prime city real estate diagonally across from the much-loved Flinders Street station, do not bode well. With its steel, glass and marble frontages, and lipstick-shaped 38-storey tower, it is the architectural equivalent of hotel lobby muzak: the kind of bland structure that would be just as at home in Dubai, Phoenix or Shandong.

And the exterior of the main hotel, which Packer inherited from the original developer of the site, is fairly inoffensive compared with its ridiculously gauche interiors. They bring together a mish-mash of styles that the famed Melbourne-based architect Robin Boyd, who penned The Australian Ugliness, would have recognised as “featurism”. Art deco lounges are approached through corridors lined with Roman mosaics. Classical Greek columns support walls decorated with the kind of mogul-style latticework normally found in Rajasthani palaces, along with Japanese idioms imported from Kyoto. The references are so eclectic that on turning another corner, one half expects to be confronted by a pyramid or giant ziggurat. The entrance stairwell, with its marble excesses and dancing fountains, looks like a monument to bogan living. Outside, on the river promenade, eight rectangular pillars become giant flame throwers after nightfall, shooting balls of fire into the sky at hourly intervals — you’ve heard it said, “It’s Vegas on the Yarra”.

For anti-casino protesters, the aesthetics are less of a concern than the addictiveness of the product that Packer is peddling. And although the NSW government insists the project will never include poker machines, figures such as Tim Costello sniff an empty promise, and a dodgy business plan. “My simple contention,” says Costello, “is that huge numbers of Chinese tourists will not fly over Singapore, Taiwan and Taipei to come to Sydney to gamble.” Besides, the Star casino, which has recently undergone an $860 million upgrade, is already trying to tap the high-roller market.

If the high-roller business model fails, Costello fears that Packer will lobby, successfully, for pokies. After all, other Australian casinos are kept afloat by customers drawn from a 20km catchment area. That was what happened in Adelaide, where, eventually eight years after opening, the casino in the renovated Railway Station went downmarket. “I think this will be the trajectory in Sydney,” Costello says. Put another way, the Sydney casino would be considered too big to fail. Even Packer concedes that the project is commercially audacious. Nowhere in the world has a $1 billion hotel been built, without pokies to boost return on investment. “The other shoe will drop,” a leading businessman says. “He’ll get the pokies. You’ll have a situation in gaming similar to the one his father enjoyed in television. The regulators will find it hard to resist.” For that reason, he says, the Barangaroo project is not the risky investment it seems: “With the politicians on his side, it’s like betting on a horse race after it’s finished.”

Even if the casino does remain restricted to high rollers, this is little consolation to Packer’s most vocal opponents. “It’s humiliating to suggest that an advanced state like NSW needs to make its living from providing gambling opportunities for rich globe-trotting high rollers,” John Kaye says. “It increases the government’s dependence on gambling, and the social addiction to gaming.”

As for the wider economic benefits to NSW, which Packer claims will reap an annual injection of $300 million to its economy, the UTS academic Deborah Edwards, who has studied the impact of casinos on tourism, believes they are being exaggerated. “High rollers from the Chinese market tend to go inside and stay there,” she says. “They don’t engage, and don’t have a broader impact on the local economy. That sort of tourism does not bring long-term, sustainable benefits. If everyone is inside, where’s the benefit.”

A few months before Kerry Packer’s death, Tim Costello had a surprisingly reflective conversation with Kerry about how Australia had lost its moral and ethical compass. “What I liked about Kerry,” says Costello, “is that he believed in something other than gaming. Channel Nine and his magazines. James has put all his eggs in one basket. Gaming is a zero-sum game: if he wins, it means that other people have to lose.”

Packer claims his motives are purer, and has portrayed his casino plan as an act of civic beneficence: “I’ve lived in Sydney all my life. This city has been very kind to my family for many, many years and I think this is an opportunity for us. This is more than economics for our company.” Kennett backs his friend, interpreting that, “He wants a product of his own making in his home city.” But the product on sale is essentially gambling in whatever architectural packaging it eventually comes.

Rather than seeing the tower as a legacy project, or even a vanity project, Sydneysiders might come to view it less flatteringly: as a landmark to NSW’s insatiable addiction to gaming.

- By John Richardson at 17 Jan 2013 - 10:22pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

56 min 55 sec ago

4 hours 14 min ago

4 hours 28 min ago

4 hours 45 min ago

9 hours 42 min ago

10 hours 7 min ago

10 hours 31 min ago

10 hours 40 min ago

13 hours 49 min ago

14 hours 39 min ago