Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

in memory of rosebud ....

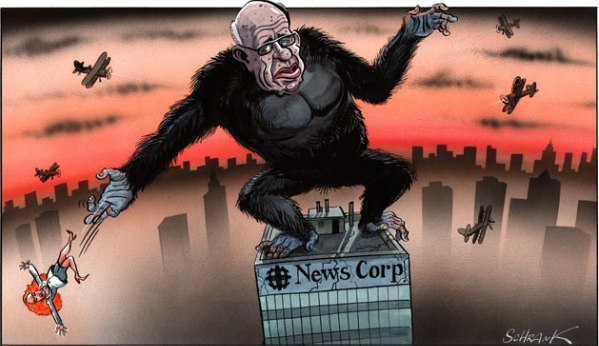

Rupert Murdoch is spending the last of his credibility on an anti-ALP propaganda campaign.

When Kevin Rudd was returned to the leadership of the Labor Party, quite a lot of voters were pleased. This was gratifying to the party chieftains, but the person they watched most anxiously was not actually a voter; indeed, he did not even live in Australia.

This was Keith Rupert Murdoch, whose newspapers had spent the past three years waging a relentless campaign against the government of Julia Gillard and all its works. So among the ALP optimists there was a wistful hope that what they described as the “hate media” might now give them a break. Quite a few News Corp columnists had been, if not actually backing Rudd, at least suggesting that his restoration might be no bad thing.

The recall of Murdoch’s chief enforcer, Col Allan, from abroad to orchestrate the empire’s election coverage was not seen necessarily as an evil omen. After all, it was Allan who in 2003 had introduced Rudd, then an Opposition front bencher, to the joys of New York’s Scores “gentlemen’s club”, at which he got legless while goggling at the pole dancers. Four years later, Rudd had to live down charges that he behaved improperly (when, in fact, his behaviour had been so proper that the next morning he rang his wife, Thérèse, to apologise).

But if the wishful thinkers believed that this earlier acquaintance would in any way soften the treatment their leader was to receive from the Murdoch press, they were very quickly disillusioned. When the polls gave Labor the boost it wanted, the attacks grew even more vicious than before. The mistake the naive optimists made was one many in politics have made before them: they assumed that the Sun King’s support was something more than an expression of his own self-interest.

Murdoch does not make lasting alliances with politicians. He forms temporary attachments, based either on what they can do for him or on how useful they can be against his enemies. While Rudd could be used to destabilise the Labor government Murdoch was determined to destroy, he could be tolerated, even given hints of support. But as soon as he was back at the helm, and was actually improving Labor’s chances, he became an abomination.

For long-term observers, there was a certain amount of deja vu in all this. Back in 1972, Murdoch had been an enthusiastic advocate for the election of Gough Whitlam as prime minister – or so it seemed. In fact, Murdoch was determined to get rid of Whitlam’s opponent, Billy McMahon, who had consistently white-anted and eventually outlasted Murdoch’s own Coalition favourite, “Black Jack” McEwen, the Country Party leader.

Having helped (though not crucially) Whitlam beat McMahon, Murdoch demanded his reward: he wanted to become Australia’s High Commissioner to London, Ambassador to the Court of St James, but at the same time to retain his role as an active newspaper proprietor. Whitlam refused, and went on to pass legislation that did some damage to Murdoch’s mining interests in Western Australia. And that was that: in 1975 the Murdoch campaign against Whitlam was so biased, so dishonest and so contrary to accepted ethical practice that some of Murdoch’s own journalists went on strike in protest. This outcome has not been, and will not be, repeated in 2013; these days those who work for Murdoch know exactly what they have signed up to.

For a few decades the ALP appeared to have got the message: if Murdoch was not to turn rabid, at the very least he needed to be appeased. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating both went out of their way to placate the rogue proprietor. It helped that Hawke was a close friend of Sir Peter Abeles, who was for a while Murdoch’s partner in Ansett Airlines; the prime minister was able to render valuable aid when the pilots went on strike in 1989. Keating, meanwhile, produced policies that generally favoured Murdoch’s interests over those of his arch rival, the John Fairfax group. It was all quite cosy.

By the time Labor regained office in 2007, it was believed that Murdoch had rather lost interest in the politics of the country of his birth. The vast majority of his business was now overseas, and he lived more or less permanently in the United States. His Australian papers obviously supported the causes that he espoused and never, ever went against his business interests, but the editors enjoyed a fair degree of autonomy. Quite a few even endorsed Rudd in the 2007 poll. Perhaps, just perhaps, Murdoch had been neutralised.

Well, no, he hadn’t, as became clear once the new government began involving itself in media policy. The National Broadband Network (NBN) was an early target. Though Foxtel, now partly owned by Murdoch, could obviously use the technology, it did not want the NBN to develop into a rival by offering direct coverage to homes, especially of sporting events. This was not an immediate issue: the NBN would take a decade or more to complete and there would be plenty of time to nail down contracts with the major sporting codes before then. Nonetheless, the Murdoch papers ran a campaign to undermine the NBN in every way possible.

More urgent was the matter of the Australia Network, the nation’s overseas radio and television service, which was put to tender in 2011, when Julia Gillard was prime minister and Rudd was serving as her foreign minister. Sky TV, of which Murdoch was indirectly a part owner, applied for the licence in competition with the ABC, which had run the organisation since it was founded as a radio service in 1939. The process turned into a shemozzle. It was widely believed that Rudd as foreign minister backed Sky (another reason for hope when he came back as PM) but the communications minister, Stephen Conroy, was implacably opposed. The decisive cabinet meeting, held while Rudd was overseas, ended with the ABC being awarded the gig in perpetuity.

With rather more justification than usual, the Murdoch forces went apeshit, and stayed that way. In the wake of the British phone-hacking furore, Gillard hit back by setting up the 2011 Finkelstein inquiry into the Australian press; many in the Labor Party made no secret of their desire to target News Ltd. And when in March 2013 Conroy proposed some fairly mild reforms to curb the worst excesses of the media, the Daily Telegraph produced a front page comparing him with Mao Zedong, Kim Jong-Un, Robert Mugabe and Joseph Stalin, before apologising the next day – to Stalin.

By this time, understandably, Gillard and her colleagues had had enough. For nearly five years the hate media had been harassing the Labor government, deriding and denigrating the stimulus measures taken to combat the GFC. The inevitable stuff-ups arising from the urgency of the programs, particularly those involving the building of school halls, had been blown out of all proportion.

There had also been repeated attempts to revive a near decades-old affair that had led to Gillard’s resignation from the legal firm of Slater & Gordon. Apparently she had unwittingly been complicit in setting up a fake union slush fund for her then boyfriend. There was no evidence that her part in the scam had been in any way criminal; at worst, she was guilty of a youthful lack of prudence. But the Australian spent months trying to make this a hanging offence, and berated the other media for not joining them.

It was now a war to the death: Gillard and her colleagues were to be given no respite. If they talked about inequality in Australia and attempted to do something about it, it was class warfare, the politics of envy. If any objection was raised against the blatantly and appallingly sexist treatment to which Gillard was frequently subjected, it was playing the gender card. And Murdoch’s hired guns were not content to be simply reactive: a senior reporter, Steve Lewis, was an active player in the laying of sexual harassment charges against Labor’s renegade speaker, Peter Slipper, if not in what Federal Court Judge Steven Rares later found to be a conspiracy to damage Slipper’s reputation.

The hope of a reprieve from the press baron played no direct part in the resurrection of Kevin Rudd on 26 June, but at least the caucus must have thought that Murdoch’s hatchet men could not treat Rudd any worse than they had treated Gillard. Then, of course, they did. The Telegraph photoshopped him as a bank robber, a Nazi prison guard from a long-defunct American sitcom, a pseudo-Rambo and Kermit the Frog – and that was just for starters. The day he called the election the paper decided to stop pussyfooting around and tell us what Rupert really thought: “KICK THIS MOB OUT!” it commanded.

From then on the entire Murdoch stable abandoned any pretence at journalism to become a hardline propaganda machine. The papers vied with each other in finding new and ingenious ways to lambaste Rudd and all he stood for. The only relief was the occasional story extolling the superhuman qualities of Tony Abbott. As in any war, truth was the first casualty. Murdoch was apparently happy to sacrifice his own credibility as long as he achieved his immediate political – and, of course, commercial – goal.

So, does all this really matter? In the past, media campaigns, however raucous, have never actually changed the outcome of an Australian federal election. Whitlam would have won in 1972 and lost in 1975 with or without Murdoch – the most the proprietor could claim was to have had some influence on the extent of the result. And Murdoch, as Rudd said with commendable moderation, is entitled to his opinion – it is, after all, a democracy. But it is not just Murdoch’s opinion: it extends to everyone who works for him. For the period of the campaign at least, much of Australia’s supposedly free press is in chains.

The extent of one man’s dominance of it is unparalleled in the democratic world. Murdoch owns or co-owns 37 mastheads, including 14 of the 21 Australian metropolitan dailies and Sunday newspapers: for some two thirds of Australians these are their primary news source, and that’s without counting Foxtel, increasingly infiltrated by Murdoch reporters, especially from the Australian. In four of Australia’s eight state and territory capitals, the Murdoch press holds an effective monopoly. This situation would be unhealthy at any time, but when its proprietor goes rogue in pursuit of a personal vendetta it becomes positively dangerous. Of course, it also has the long-term effect of discrediting the whole free media; after 1975 it took years for the Australian to rehabilitate itself, and now it will have to start all over again. The press and its practitioners already rate very low on the public-trust scale. The current exercise will only damage them further.

Newspapers have been Rupert Murdoch’s life. His conduct of the 2013 election campaign smacks of a serious death wish. Perhaps Oscar Wilde got it right: each man kills the thing he loves.

- By John Richardson at 7 Sep 2013 - 3:37pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 17 min ago

5 hours 16 min ago

14 hours 56 min ago

17 hours 53 min ago

20 hours 11 min ago

1 day 5 hours ago

1 day 6 hours ago

1 day 13 hours ago

1 day 17 hours ago

1 day 19 hours ago