Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

shinybum scopophiliacs ….

from Crikey …..

Officials admit: we can't justify data retention

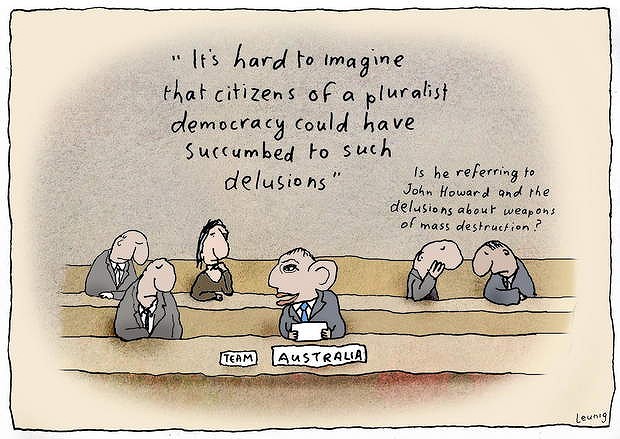

In a moment of downright Nixonian desperation, Prime Minister Tony Abbott this morning sought to dramatically raise the stakes on national security against Labor, coming out to aggressively demand that Labor back his mass surveillance data retention scheme, more than three weeks before the Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security is due to report on it. Abbott called a media conference this morning to declare, standing next to Australian Federal Police Commissioner Andrew Colvin, that metadata was "absolutely vital" to the police, who were faced with a "burning platform" that was sending them blind.

Abbott wants his scheme legislated by mid-March, allowing less than eight sitting days for Parliament to consider the biggest mass surveillance scheme in Australian history. And that's despite crucial details such as cost and the data to be retained, remaining unresolved -- indeed, government officials confirmed earlier this week that even if they had settled on the cost of the scheme, Parliament might not be told of what it will be before it is legislated -- a staggering breach of the most basic legislative processes. And in a letter leaked to The Australian by the Prime Minister's Office, Abbott also demanded that Opposition Leader Bill Shorten fall into line on the proposed data retention bill.

But the timing is a little problematic for Abbott, because in the last week, we have seen just how little basis there is for Abbott and Colvin's claims.

You'd have thought the burden of proof for the effectiveness of mass surveillance would have lain with advocates, and particularly with the bureaucrats of the Attorney-General's Department, who have been pushing to keep a copy of every Australian's digital lives since 2008. It's a burden they have signally failed to carry.

As Crikey has repeatedly noted, there is no -- as in, literally, no -- evidence that mass surveillance, whether of simple data retention or of collection of web browsing history or industrial-scale root-and-branch NSA surveillance, has had any benefit in relation to counter-terrorism 0r law enforcement. Zip, nought, nothing, despite being used in a variety of European countries, the United States and the UK (I summarised the dearth of evidence in this private submission). Indeed, the terrorist attacks in France and the Sydney siege, which Abbott this morning invoked as justification for data retention, were both perpetrated by men well known to security agencies -- at various points they had been under active monitoring. Both cases are reminiscent of the Boston bombings, the perpetrators of which the FBI had been warned about by foreign intelligence agencies.

At the data retention bill inquiry last week, some members of the Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (the Labor members of the committee and South Australian Liberal David Fawcett are the only ones on that committee doing their job properly) put police representatives on the spot to provide evidence of the benefits to criminal investigation of data retention. In response, there was much verbiage from the uniforms about why they couldn't actually provide any evidence of that. A representative of the NSW Police Force -- currently imploding over the mass surveillance of its own officers carried out allegedly in breach of legislated warrant requirements by senior officers -- told JCIS "we do not keep a central repository of the effectiveness of metadata", then reeled off some statistics on crime clearance rates, followed by "we are not saying they were directly attributable, but there was some value, some effectiveness or some evidence given in those court proceedings in relation to metadata". That's as good as it got for actual evidence about the effectiveness of data retention in fighting and solving crime -- and that's from a police force that is alleged to illegally bug its own officers, let alone ordinary citizens.

Oddly enough, the lack of evidence echoes the European experience, where efforts to find evidence that data retention is useful for addressing serious crime, have come to naught.

In a different committee earlier this week, Greens Senator Scott Ludlam, who is almost single-handedly running a Senate inquiry into the telecommunications access regime, put similar questions to AGD officials, including Anna Harmer, now famous for giving evidence to committees like she's just drunk half a dozen coffees and enrolled at auctioneer school. Somewhat slowed to a mere 400 words a minute by Ludlam's preference for asking hard questions rather than bowling up full tosses like several members of JCIS, Harmer and her minions were similarly unable to to furnish any evidence either that a requirement that security agencies obtain a warrant to access metadata -- as exists in many European countries -- would cause law enforcement to "grind to halt", as claimed by the spooks and the uniforms, or that data retention actually helped.

"The evidence in support of data retention is not cast in terms of clearance rates," Harmer machine-gunned at Ludlam. That is, not merely are advocates of mass surveillance unable to furnish any verifiable evidence that it has worked in the past, they say we won't be able to tell if it has worked in the future, either -- data retention is a policy that can never be objectively assessed to determine whether it works. "I could refer you to some of the evidence of the law enforcement agencies ..." Harmer suggested, going on to explain that it was very difficult to identify any quantifiable impact from police being able to access your personal metadata. The whole exchange can be found here, and stick to the very end for the absolutely filthy look on the AGD bureaucrat's face when Ludlam calls it "anecdote-based policy" and complains about the lack of any evidence from them.

What also emerged in Ludlam's hearings was the extent to which the online dimension (as opposed to the phone dimension) of data retention would be easy to circumvent. The discussion didn't focus on tools like VPNs or Tor, but rather, on the number of services that people could use and, under the current bill, never be identified for their internet usage, in public libraries and facilities that provide free wi-fi (like Parliament House), and via overseas service providers like Gmail, social media and IP-based messaging apps.

None of this is new -- it's in the bill, and the limitations of the reach of the online aspect of the proposed legislation were discussed months ago. But it's a further reminder of why data retention doesn't work and has had no demonstrated impact on crime clearance rates, because any criminal or terrorist with half a brain can easily circumvent the online aspect of data retention either by using Tor or a VPN, or using the increasing suite of services like Whatsapp that use end-to-end encryption, or just using their device in a place with free public wi-fi.

And when data retention spurs the further uptake of encryption and anonymisation by Australians who don't want their government, corporations and hackers to obtain their online histories, security agencies and the shinybum scopophiliacs of AGD will demand yet more surveillance powers, just as they're justifying data retention now by blaming Edward Snowden for encouraging people to start encrypting.

Surveillance state advocates can't furnish any evidence that data retention works, or that law enforcement would "grind to a halt" if security agencies were asked to get a warrant when they accessed someone's metadata. They can't produce any data that contradicts the evidence from other countries that data retention doesn't work and that law enforcement agencies cope just fine with external authorisation requirements. And it's easy to see why -- when it comes to the online aspect of the bill, evading it is child's play.

- By John Richardson at 5 Feb 2015 - 5:39pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

15 min 1 sec ago

31 min 34 sec ago

56 min 43 sec ago

4 hours 4 min ago

8 hours 13 min ago

8 hours 23 min ago

9 hours 59 min ago

10 hours 53 min ago

11 hours 54 min ago

12 hours 20 min ago