Search

Recent comments

- patriotism....

2 hours 34 min ago - belittling russia......

3 hours 1 min ago - Запад толкает Украину на последнюю битву....

3 hours 15 min ago - fourteen points....

3 hours 24 min ago - der philosophische glaube....

3 hours 35 min ago - seriously?...

3 hours 50 min ago - AfD....

4 hours 17 min ago - undesirables...

4 hours 33 min ago - assistant spies......

4 hours 58 min ago - brics.....

8 hours 6 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

ordained genocide ...

Our article this morning by Kathy Stavrou: ‘Caught in the Act‘ and her subsequent Facebook comment that her article summarised “how successive NSW Governments used legislation as social engineering to extinguish Aboriginal property ownership rights” had me scurrying to an article I wrote many years ago. There was an agenda in both the colonial and early federal governments; that being the extermination of Aborigines. Not only was it the will of ‘man’ that Aborigines be exterminated, but also the will of God. Or so they believed.

I wrote:

Was the total extermination of Australia’s Indigenous people deliberately intended? Of course it was. It was OK to shoot Aborigines. God had no problems with good white Christians killing Aborigines as it was the white man’s belief that God had condemned Aborigines to extinction and the white man was simply hurrying things along for Him. It had His stamp of approval. It was ordained genocide.

But the massacre of Aborigines was frowned upon by latter Colonial and Federal Governments, however, it did not mean that they were not considered a doomed race. These governments had a sinister role to play in that consideration; that of the evolutionary masters. That of God.

Let us trace this.

The nineteenth European scientific discourse of the Great Chain of Being arranged all living things in a hierarchy, beginning with the simplest creatures, ascending through the primates and to humans. It was also practice to distinguish between different types of humans. Through the hierarchical chain the various human types could be ranked in order of intellect and active powers. The Europeans – being God-fearing and intelligent – were invariably placed on the top, whilst the Aborigines – as perceived savages – occupied the lowest scale of humanity, slightly above the position held by the apes. Such ideas were carried to and widely circulated in the Australian colonies and helped shape attitudes towards the Aborigines. So dominant was the concept that it helped develop the fate of Aboriginal people, even before Australia’s colonisation. The image of the Aborigine simply confirmed prejudices based on this doctrine of evolutionary difference and intellectual inferiority.

In harmony with the Great Chain of Being, the theory of evolution in the social sciences (known as Social Darwinism), was accepted by nineteenth and early twentieth century Australians as further justification for their treatment of the Aborigines. Central to the theory of Social Darwinism was the ideology that the Aborigines, who were considered to be less evolved, faced extinction under the impact of European colonisation and nothing could, or should, be done about it. Government policies reflected these ideologies and provided the validation of oppressive practices towards the Aborigines, founded on the perceptions of racial superiority.

Four of the major policies are those relating to protection; segregation; assimilation; and the integration of Aboriginal people into the wider community.

Protection was influenced by the evolutionary theory that Aborigines would die out as a result of European contact. Subsequently, all that could be done was to feed and protect them until their unavoidable demise. The policy thus took on short term palliative measures that saw enforced concentration of Aborigines in reserves and missions – protected from European contact and abuse (such as hunting parties) to await their closing hour.

This policy was a humane one based on its presumptions, however, nature had not selected Aborigines for extinction. Only the colonisers had. Subsequently, governments eventually and willingly used protection policies as a mechanism for social engineering. The policies of protection changed its fundamental goal to segregation. Their differences are difficult to identify although their purposes are not: Aborigines were a dying race so they were protected from the wider community; the Aboriginal race had failed to die off, so they were segregated from the wider community.

The social theories that legitimised and institutionalised racism were never more evident than in the practices of segregation. Segregation created two social and political worlds in Australia: one white and one black. Whilst the Aboriginal race had ignored extinction, Government policies reflected the attitude that, nonetheless, by the 1940s they had still failed to progress since European contact. Sentiment thus ruled that continued segregation of the Aborigines from the wider community would ensure white racial purity.

Segregation was pervasive in all aspects of public or political life. Church or social organisations discouraged Aboriginal participation, and access to community facilities such as swimming pools or theatres were severely restricted, if not refused altogether. Custom in many business establishments was also refused for fear of offending the white clientele. Perhaps the most damning indicator of this racism, however, was the neglect of medical treatment and health services by white practitioners. Policies of segregation were to degenerate into practises of apartheid when, in South Australia for example, association between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people became a criminal offence under Section 14 of the Police Offences Act 1953.

The policies of protection and segregation were continued even though the Aborigines had not faced their final hour. ‘Full-bloods’ remained on reserves until their demise, yet the problem for the government came in the form of the ‘half-caste’. These people looked increasingly like white people but behaved like ‘Black’ people. The only was this could be countered was to assimilate them into the general population.

Assimilation of the lighter-caste population was still an endeavour to destroy Aboriginality: by absorbing them into the wider community – the breeding out of the colour, the process of genetic change – it was hoped that they would eventually disappear. A radical suggestion that selective mating would breed out the colour was also proposed.

Of the endless record of horrors associated with colonisation and racial supremacy, some of the assimilation policies adopted in the 1950s equal the worst. In particular the taking of children away from their families by the Protection Board – as their legal guardians – and disposing of them as they saw fit. As a prelude to the Reconciliation Convention, the Government reflected on this practice:

Children were taken away under government policies of protection and assimilation aimed at having indigenous people adopt European culture and behaviour to the exclusion of their family and background. The assimilation policy presumed that, over time, indigenous people would die out or be so mixed with the European population they became indistinguishable (The Path to Reconciliation, 1997, p 24).

Yes, I would argue that the total extermination of Australia’s Indigenous people was deliberately intended. If not by the bullet, then by the policies of those governments that saw them as a stain on white purity. God favoured the white man and they set out to do His work.

- By John Richardson at 5 May 2017 - 7:01pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the savages are killing each other and other fake news...

Protocol always comes before business of course, so we sit with our cappuccinos and make our connections there beneath that white steel tower, alongside pigeons and seagulls fighting for scraps. We find our kin relationship through our connected brolga and black cockatoo totems. We find joy in the hard “th” sounds of our speech, in language sounds we seldom hear this far south. Our yarn moves on to the magpie geese that migrate each year from Cape York to Victoria, following song lines magnetised as pathways in the sky.

Magnetised is the right word for it, we think. We reflect on our own journeys over the years from north to south along those same lines our ancestors have travelled for trade since time out of memory. Those geese are still doing it and so are we.

I make a joke about his new mohawk haircut, laughing that it looks like he’s going to war. He laughs back, “I am going to war!” So we get serious, get down to business, and he tells me the story of his century-old battle.

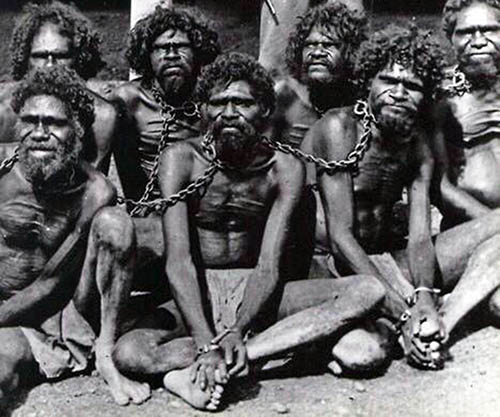

In 1892, 22 men, four women and one child were forcibly abducted and placed in chains by a Scot called Archibald Meston, who would later become the chief protector of Aborigines. The people he abducted were from the lands of the Wakaya, Kuthant, Kurtjar, Arapa, Walangama, Mayikulan, Kabi Kabi, Kalkadoon and also from Muralagin the Torres Strait. Jack’s family were among the abductees.

They were forced to rehearse traditional and choreographed dances in the canefields where the University of Queensland stands today. The dances were to be the highlight of a travelling show. This “Wild Australia” performance went on to tour Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne to great acclaim, enriching Meston through the exploitation of his captives.

At each stop, the men were forced to pose for colonial propaganda photos depicting native police massacring their “savage” countrymen – the message being, “Hey, we’re not perpetrating this genocide; the savages are killing each other!”

Read more:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/may/06/wild-australia-reli...

the frontier wars...

Colonial frontier massacre is a largely under researched topic in Australia. Most studies of massacre relate to particular incidents, such as Risdon Cove in Tasmania (1804) which remains highly contested even today or at Myall Creek (1838) where all but one of the twelve perpetrators were arrested and brought to trial and seven of them were convicted and hanged.1 Such incidents are considered as unique and overshadow other incidents that are simply lost from sight.

Australia wide studies of frontier massacre such as Bruce Elder’sBlood on the Wattle, those by Timothy Bottoms for Queensland, Patrick Collins for the Maranoa, Tony Roberts for the Gulf Country and Geoffrey Blomfield for the Three Rivers region in New South Wales, have certainly made the case for its widespread incidence but none of them offers a definition of frontier massacre or seriously considers its characteristics.2 A similar oversight prevails in the various massacres lists that are available online.3

DefinitionA colonial frontier massacre arises from the indiscriminate killing of six or more undefended people. Why six? The massacre of six undefended Aboriginal people from a hearth group of twenty people is known as a ‘fractal massacre’.4 The sudden loss of more than twenty per cent of a group leaves the survivors vulnerable to further attack, a greatly diminished ability to hunt food, to reproduce and carry out their ceremonial obligations. In turn they become vulnerable to exotic disease.

read more:

https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/introduction.php

see also:

https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/map.php

trading places...

The Cape York community of Coen, home to just over 300 people, has a violent past as a mining camp and police base.

"It was set up to gather the Indigenous people from out in the bush and chain them up and bring them into Coen ... to get them off the country," says artist and Kaantju traditional owner Naomi Hobson.

Now, in collaboration with photographer Greg Semu, Hobson has set out to explore this history by recreating brutal archival images.

But in Semu's images the script has been flipped — often the victims pose as abusers. And the entire Indigenous community of Coen was involved in the recreations.

Today, eight Indigenous clan groups reside in Coen, living alongside a handful of non-Indigenous families who trace their ancestry back to gold miners.

Hobson, who has been based in the town her entire life, says her community has often been unwilling to talk about its past.

"They come from that history where they couldn't speak about where they came from, they couldn't speak their language ... they were treated like cattle basically.

"Just rounded up from the bush and taken into a reserve that was fenced in."

Though Coen's residents have learned to live together, Hobson believes the project, which is on display at the Cairns Art Gallery, has sparked much-needed conversations about the community's brutal past.

read more:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-07-19/restaging-violent-historical-photo...

Coen is full of smart people. I pass through there in the early 2000s, and I felt at ease, accepted for being human. This role reversal is clever in pointing out the injustices of the past, present and future.