Search

Recent comments

- breeding insanity....

3 hours 8 min ago - american "diplomacy"

6 hours 5 min ago - deceit america....

8 hours 24 min ago - police-state....

18 hours 4 min ago - the war continues....

18 hours 52 min ago - scott is angry.....

1 day 1 hour ago - a catastrophe?....

1 day 5 hours ago - 3Xwars is 3Xpeace?....

1 day 7 hours ago - futile trousers....

1 day 7 hours ago - reading reality....

1 day 8 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

wall street .....

In a recent debate Congressman Ron Paul claimed the United States military had troops in 130 countries. The St. Petersburg Times looked into whether such an outrage could actually be true and was obliged to report that the number was actually 148 countries. However, if you watch NFL football games, you hear the announcers thank members of the U.S. military for watching from 177 countries. The proud public claim is worse than the scandalous claim or the "investigative" report. What gives?

Americans are supposed to be proud of the U.S. empire but to reject with high dudgeon any accusation of having an empire. Abroad, this conversation makes even less sense, because those troops and their bases are in everyone's faces. Near Vicenza, Italy, years ago, the people tolerated the U.S. Army base. The addition of a many-times larger one in the same town, now underway, has led to outrage, condemnation, and bitter resentment of being handed second-class citizenship in one's own country while being asked to show gratitude for it.

As President Obama encircles Russia with missile bases and China with naval bases, the people who live or used to live where the bases are built resent the occupation, just as the people of Iraq and Afghanistan resent the occupation. A global movement against U.S. military bases is rapidly rising from all corners of the empire. But so is a movement against the occupation of Der Homeland by an unrepresentative and unrepresenting police state.

Those not in the Forbes 400 have been handed second-class citizenship in the place they are supposedly protecting through the occupation of every other place. A large majority of Americans want the rich and the corporations taxed heavily, but they are not. They want the wars ended, the troops brought home, and military spending cut. None of this happens. Nor do the outcomes of elections impact the likelihood of any of these things happening.

The majority of Americans want to keep and strengthen Social Security. They want Medicare protected and expanded to cover us all. They want rights enlarged for human beings and curtailed for corporations. They want to cut off the corporate welfare and the bankster bailouts. They want investment in infrastructure, green energy, and education. They want the right to organize and assemble. And they want a clean system that allows public pressure through ordinary means: publicly funded elections, verifiable vote counting, no gerrymanders, no media and ballot barriers to candidates. None of this is forthcoming. They are paying taxation and receiving no representation.

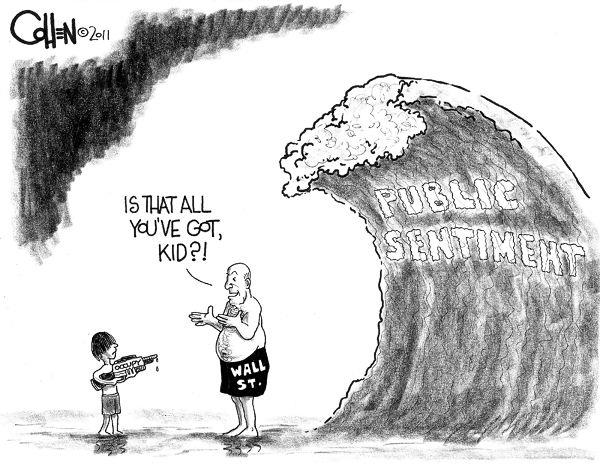

Now they are occupying Wall Street. They will not be moved. Without anyone having to set themselves on fire, a group of nonviolent fed-up people, young and old, has sparked something new. In less than two weeks they have gone through all of the stages of public protest: being ignored, mocked, attacked, and beginning to win. People are joining together across race, age, gender, and culture. Labor unions are joining in a movement that was not begun by labor unions. Insider groups that would rather not be seen at protests are promoting this one. Cable television is denouncing police brutality.

A conversation has been launched about the damage the wealthiest one percent is doing to the rest. And integral to the demand being made for social justice is the demand to cut military spending and end immoral wars. Now is the moment to nonviolently resist on Wall Street (http://occupywallst.org) and around the country (http://occupytogether.org). Wall Street's servants on K Street, in the Pentagon, and in our government think Wall Street is comfortably far away.

Anti-Wall Street protests have continued to spread to cities across the US. According to the web site Occupy Together, as of Friday evening "Meetups" to plan protests had been established in more than 900 cities.

The Occupy Wall Street movement, which began last month in New York, has expanded now to dozens of towns, including Tampa, Florida; Norfolk, Virginia; Washington, DC; Boston; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Chicago; St. Louis, Missouri; Minneapolis; Houston, San Antonio and Austin, Texas; Nashville; Portland, Oregon; Anchorage, Alaska; and a number of California cities.

The demonstrations-fueled by anger over social inequality, unemployment and a vast decline in living standards for the overwhelming majority-are also gaining international support. There are calls on Facebook for a global demonstration on October 15 in cities in more than 15 countries, from Dublin to Madrid, Buenos Aires to Hong Kong.

"Occupy Melbourne" in Australia is planning an October 15 protest in City Square, and similar calls are being organized on Facebook for protests in Sydney, Brisbane and Perth. The "Occupy the London Stock Exchange" Facebook page has more than 6,000 followers, and has announced plans to occupy Paternoster Square beginning October 15.

The spontaneous outburst of anger at the banks and big business, which has struck a chord with wide layers of the population, has been met with arrests and police harassment and brutality in a number of areas. It has also come under attack from sections of the political establishment, and has been given generally short shrift in the mainstream media.

In comments to the Wall Street Journal on Thursday, Republican presidential contender Herman Cain denounced the protesters as "anti-capitalism," and added, "Don't blame Wall Street. Don't blame the big banks. If you don't have a job, and you're not rich, blame yourself."

His sentiments were echoed on Friday by US House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, Republican of Virginia. Speaking at a "Values Voter Summit" in Washington, he decried "the growing mobs occupying Wall Street and the other cities across the country."

Cantor's remarks followed President Obama's comments the day before, in which he claimed to "feel the pain" of the protesters, but defended the $750 billion TARP bailout of the banks, and affirmed his support for "a strong, effective financial sector in order for us to grow." He stated that the actions of the banks and speculators were not "necessarily illegal" and that it wasn't his job to prosecute them.

In New York City where the Occupy Wall Street protest began, Mayor Michael Bloomberg lashed out at the protesters in comments on his weekly radio address Friday. He claimed, "The protesters are protesting against people who make $40,000-$50,000 a year and are struggling to make ends meet."

Presumably the mayor was referring to service workers, not the corporate billionaires who have earned the wrath of the thousands of people mobilized in the anti-Wall Street protests. He also made the fantastic claim that "we all" shared the blame for the economic meltdown and recessionary crisis by taking on too much risk.

Bloomberg defended the violence that has been meted out against the protesters by New York City Police Department, stating, "The one thing I can tell you for sure is if anybody in the city breaks the law, we will arrest them and turn them over to the district attorneys."

New York's Occupy Wall Street has been met with excessive police force since the protest began last month. Just last Saturday, some 700 demonstrators were arrested after they had been led into a trap by police on the Brooklyn bridge.

- By John Richardson at 9 Oct 2011 - 7:57am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

copping-it sweet .....

When it comes to executive pay, the market is broken. The game, you might say, is rigged.

Chief executives and their assorted lobby groups are fond of saying "That's the market" when it comes to defending the massive salaries. "Look at America," they cry. "You have to pay top dollar to attract the best talent!"

Indeed, look at America. The Wall Street protests are now in their fourth week. And even though the protesters have struggled to identify, let alone voice a clear message, they know something is awry.

But more of this later. Australia is in far better shape than America thanks to high commodity prices, yet it faces the same challenges to its free-market system.

And nowhere is the market's failure more clearly enshrined than in the debate over executive pay. Here - the system's ultimate incarnation of self-interest - is where the rubber really hits the road.

Once again this year, executive pay is rising strongly while share prices are down and returns to shareholders falling. If markets were functioning properly, executive pay would fall when returns to shareholders were falling; pay would match performance, risk would match rewards. Yet they don't.

When it comes to executive remuneration, pay has failed to match performance for 20 years - ironically ever since the mandatory disclosure of salaries was introduced in the early 1990s. We will get to that too, in due course.

Ever widening gap

In the meantime, a few data points to prove the case:

The Australian Council of Super Investors (ACSI), the body which represents industry super funds, marked its ten-year anniversary last month with a ten-year study on executive pay.

It found the decade to 2010 saw median CEO fixed pay in the Top 100 ASX Australian companies rise 131 per cent and the median bonus increase 190 per cent.

This far outstrips the 31 per cent increase in the S&P/ASX100 over the 10 years.

"The findings ... also indicate that while CEO cash pay - the value of pay disclosed excluding share-based payments - has fallen from the peak of 2008, it remains much higher than any year before 2007," said the ACSI report. "This is despite the S&P/ASX100 declining 30 per cent over the three years to June 30, 2010.

"Median cash pay for top 100 CEOs in 2010 was $2.786 million, down 2.4 per cent from 2009 and 4.1 per cent from the record peak of $2.904 million in 2008. Despite this decline, median cash pay for a CEO of a top 100 company in 2010 was 12 per cent higher than any year prior to 2007."

So, we have workers' pay rising roughly 3 per cent a year, and the average super fund return over the decade little more than 3 per cent as well. Nonetheless, executive salaries put on double digit returns.

How can this possibly be regarded as a functioning market?

The market is broken. Supply and demand are not intersecting efficiently. On the supply side, there are plenty of contenders for CEO roles. Scarcity is a bogus argument - especially as there is no credible evidence that paying more money achieves a better result. The argument of higher pay for higher performance is based more on lobby group chimera than empirical evidence.

The mostly alpha-male types who inhabit high executive ranks are there as much for the competition, the power and the vanity, as they are for the money. Will $10 million really make a Gail Kelly or a Ralph Norris perform twice as well for Westpac or Commonwealth Bank as $5 million?

Sol Trujillo, the former Telstra CEO drafted in at great expense from the US, is the quintessential example of frittering away shareholders' money on a false proposition, that is, that Telstra had to go to the US and pay top dollar to get the best.

Trujillo cost nearly $30 million in cash earnings in his four-year tenure, notwithstanding questionable no-tender deals for related parties, while Telstra shareholders' wealth went backwards.

Executives aren't the owners

Now it is true that top executives face pressure, long hours and enormous responsibilities. Of that there is no doubt. They should be compensated for these aspects. Theirs is a cutthroat game, an occupation whose rewards should reflect its risks.

The question is one of degree. It is simply one of numbers - the market.

The CEOs of our Big Four banks are paid $10 million salaries despite presiding over corporations that cannot go bust. As finally made explicit in the financial crisis via the government guarantees, we, the taxpayers, stand behind our banks. We guarantee them. They cannot go bust.

No small business in this country is afforded such protection, such an elevated status of taxpayer support. This is not a real market because failure, or lack of risk of failure, is not priced into executive salaries.

It should never be forgotten - although it often seems systemically overlooked - that executives are not the owners.

The owners of the company are the shareholders. The board of directors, on behalf of the shareholders, appoints the executives and decides the salaries.

This is the theory, but sadly the reality is the executives behave like the owners and the directors too often act in the interests of the executives rather than the owners, the shareholders.

This "market for executive labour" is also broken because of the large voting blocks of company shares that are controlled by funds managers, or "institutions".

Money managers join top league

There is a problem here. Many years ago, these money managers were typically low-key types, but the explosion in super money in the 1990s entailed a concomitant explosion in funds managers' fees and salaries.

Suddenly this was a large industry, feting itself with awards and excessive fees. Soon the funds managers who were either good self-promoters or whose funds had performed better than the average were able to earn million-dollar salaries themselves.

The stars at MLC, Perpetual or Colonial Funds Management were now in the same remuneration league as the executives of the companies whose shares they controlled.

They too, just like the executives, were simply stewards of other peoples' money. Yet the stewards had the control. They were now running the show.

These institutional investors, although single shareholders, often speak for large blocks of shares, perhaps half the issued share capital of your average listed company.

Unlike the vast body of smaller shareholders though, the funds managers have regular meetings with big company management. They get to talk to executives and whereas executives only have to face all shareholders once a year at the annual general meeting, they are in constant contact with the funds who are their major shareholders.

Executives then really only have to keep a few big funds managers "sweet" to get their pay rises approved. Even if small shareholders revolt, via a rejection of the non-compulsory "remuneration report", their pay rises are pushed through by the institutions.

Again, institutions do reject executive excess from time to time, but this is the exception, not the rule.

In a sense, the funds managers - many of whom will privately confide their million-dollar pay deals are somewhat over-the-top - have a vested interest in seeing executives overpaid. It vindicates their own excess.

The upshot of this voting control however is an inefficient market for executive pay.

As a breed, funds managers are not given to rocking the boat. And the mere gratitude which accompanies the honour of a one-on-one meeting from a high-flying executive is enough to sway a 'yes' vote on a proxy form.

And so it is that executives "do the rounds".

What are my peers getting?

How did it get to this? When it comes to financial markets, disclosure is almost always a good thing. In the case of executive pay however, it was a bad thing.

When mandatory disclosure of a company's top salaries was introduced in the early 1990s, all of a sudden every executive could see from the annual reports what every other executive was earning.

It was a disaster, immediately, spawning an entire new industry of "remuneration consultants" or "RCs".

BHP is known, for instance, to use up to five RCs just to tell it how to price labour in its very own market.

Underpinned by that basic human principle that there is nobody that argues that he or she is overpaid, the public disclosure led to a spiral in executive pay which is still out of control two decades later.

The only ceiling appears to be a company's finite resources and, sometimes, shame.

The RCs go from company to company doing reports which corroborate every executive's view that they should be paid more, on whatever measure. And there is always a measure which can be brewed up to rationalise a bonus for this or that.

Indeed the RCs have been instrumental in adjusting the mix of remuneration. A weekend BusinessDay study, for instance, showed that total remuneration actually fell in median terms by 1.3 per cent to $3.52 million in Top 100 companies last financial year.

Bear in mind, shareholders wealth fell a lot more than that. Still, the actual cash component of the pay, both base salary (plus 9 per cent) and cash bonuses was up.

In the lean times the RCs skew executive pay to a more secure and cash-based mix while long-term performance based on share price tends to be favoured when the market is running hot.

Anger on Wall Street

And so, looking at the market for executive labour, there are undoubted inefficiencies. Risk and reward are not evenly priced. The game is rigged.

And this inefficiency is fundamental to the crisis of capitalism generally, hence the Wall Street protests.

In the US, political donations have entrenched corporate power in Washington to such an extent that democracy has been kneecapped. The political process can no longer make decisions in the broader national interest.

Washington is virtually broke, unable to govern decisively without blowing out the debt ceiling, while corporate balance sheets are ship-shape and corporate and high net worth taxes are lower than ever.

The rich are richer, the poor are poorer and with unemployment - even on official figures at 9 per cent - so high, people are finally taking to the street.

Had Wall Street not been rescued by Main Street, had capitalism in its pure form been permitted to function and had Washington not resorted to corporate welfare, it would have been a different story.

Democratic process contaminated

Capitalist system progressed to ultimate form. Now the political power of the corporations has contaminated the democratic process.

We should be mindful that it does not happen here. Unfortunately, if the weekend splash in the Herald is any guide, we are already well down that road.

That a business leader, chairman of the Business Council of Australia Graham Bradley was considerate enough to offer Prime Minister Kevin Rudd "a lifeline" in June last year - in return for Rudd backing off on the mining tax - would suggest the democratic process has already been rattled hard.

Rudd was soon axed after declining Bradley's offer. Julia Gillard took over the government leadership and quickly backtracked on the mining tax.

That a business leader - especially one acting in the interests of three multinationals with majority overseas ownership (BHP, Rio and Xstrata) - can affect the political process in such a dramatic way behind closed doors ... it's not a good sign of things to come.

The great paradox, of course, is that in influencing the political process and keeping their companies' tax burden low, the CEOs of BHP Billiton, Marius Kloppers, and Rio Tinto, Tom Albanese, have earned every cent of their $10 million-plus salary package.

Executive Pay - The High Cost Of Market Failure

from the deep end of the trough .....

from Crikey .....

Exec pay: heads executives win, tails shareholders lose

Adam Schwab writes:

EXECUTIVE SALARIES

With executive pay season well and truly upon us, well-healed boards continue to adopt a convenient "heads executives win, tails shareholders lose" approach to remuneration.

While the astronomical Allan Moss/Phil Green-style salaries have temporarily stopped (the former Masters of the Universe collected upwards of $30 million annually before the global financial crisis) -- institutional shareholders are becoming increasingly agitated at boards' willingness to pay executives even where performance has been lacklustre.

Wal King and Rupert Murdoch stand alone in terms of pure obscenity: King stands to collect almost $30 million in termination payments and salary this year while Leighton's share price remains a smoldering ruin. Rupert, meanwhile, almost comically takes home $US33 million, including a $US12.5 million cash bonus, for overseeing a company that is facing criminal and civil investigations for phone hacking, Dow Jones circulation scandals and the increasingly regular multibillion corporate blunders, such as the Dow Jones and MySpace.

If market watchers were in any doubt as to why Queensland Rail executives were so enthusiastic to float on the ASX after 145 years of government ownership, a quick look at CEO Lance Hockridge's pay packet would dispel any doubts. In 2006, the former CEO of Queensland Rail, Bob Schueber, was paid $447,000. In 2010, when QR was still owned by taxpayers, Hockridge received $981,000. This year, despite doing the same job, with sales increasing by a relatively pedestrian 11%, Hockridge scooped up more than $3 million in cash alone, and almost another million in share-based payments.

Hockridge's pay rise was assisted by the usual suspects, with high-price remuneration consultants Egan, Deloitte and PwC providing "advice" to the QR board. It was, of course, imperative that Hockridge was paid "market" rates, like those paid by Asciano to former CEO Mark Rowsthorn (who oversaw a share price decline of 86%). Apparently, the job of running QR National is 10 times more difficult now, as it was five years ago.

Then there's the curious case of the mysterious, disappearing, return on equity at Wefarmers. The Western Australian conglomerate, under the guidance of Trevor Eastwood and then Michal Chaney, famously adhered to a slavish following of making investments that delivered a strong return on equity -- this allowed the company to deliver return on equity of 25% to shareholders and years of strong shareholder growth.

That all ended in 2007, when current CEO Richard Goyder led Wesfarmers on a risky and costly acquisition of Coles, shortly before the onset of the global financial crisis. Following the $20 billion purchase of Coles, Wesfarmers return on equity slumped to 6.4% last year, recovering to 7.7% this year. Earnings per share this year were $1.66, down from $1.95 in 2007. This was due to the company having to undertake a hugely diluted share issue to fund the acquisition.

While the underlying Coles business, under the guidance of Ian MacLeod, is improving -- from a financial perspective, Goyder's acquisition remains a semi-disaster. This, of course, hasn't stopped Goyder from being extremely well paid -- largely because the Wesfarmers board conveniently widened the goalposts.

This year, Goyder was paid $3 million fixed pay, and a further $2 million cash bonus (Goyder also received $1.5 million in share-based remuneration). However, just in case $5 million in cash isn't enough for Goyder, the Wesfarmers board noted that:

"The performance rights previously granted to Mr Goyder in 2008 under the Rights Plan did not satisfy the challenging performance condition set at the time of the initial grant, which requires a return on equity of 12.5%, achieved in two consecutive years prior to 2014 ... Mr Goyder did not receive a long-term incentive grant for the 2011 financial year.

"The board is proposing that, with effect from the allocation made in November 2011, [Goyder] will participate in the [company's long term incentive plan]."

To translate -- after appointing Goyder, the board offered him a long-term incentive that would vest if the company's return on equity was 12.5%. Despite the claims, this target was not "challenging" at all -- in fact, it was half the level being achieved before Goyder became CEO. That meant by leading the company to performance that was 50% worse than before he took over, Goyder would receive a bonus.

But if that wasn't a low enough hurdle, this year, the board is lowering the bar even further, allowing Goyder to receive a share-based bonus despite the company's return on equity has slumped to 7.7%. The company has allowed Goyder to be remunerated under the company-wide long term incentive, which is based on a "forward looking performance period".

As a final insult to shareholders -- in the event that they have the audacity to reject Goyder's appalling pay plan, the "company intends to provide Goyder and [Wesfarmers finance director] Terry Bowen with a cash benefit that will place each of them, insofar as possible, in the same after tax position as they would have been".

While the Wesfarmers board is happy to hold a proverbial gun to the head of shareholders, Wesfarmers owners do have one other option. Instead of voting against the equity grant, they could vote against re-election of Bob Every (chair of the remuneration committee) and Charles Macek (who is on the remuneration committee, and once claimed to have "written the book on corporate governance"). Given the Wesfarmers board clearly cares not for shareholder returns, perhaps it's time for Wesfarmers shareholders to send a message of their own.

divine rights .....

from Crikey ....

On executive pay, Don Argus just doesn't get it

Adam Schwab writes:

BHP BILLITON, DON ARGUS, EXECUTIVE PAY, KEITH LAMBERT

You've got to hand it to Don Argus. The former CEO of NAB, turned Australia's most prolific board member, certainly is willing to speak his mind. The only problem is, Argus appears to be completely confused as to the role of company directors and the status of shareholders.

At the launch of an AICD/Mercer study in shareholder and institutional engagement, Argus decided to attack shareholders who weren't happy with executive pay. Instead of taking action to protect their investment, Argus gave some blunt advice to shareholders. If investors didn't like how a board unilaterally decided to pay its hired help, they should "sell their shares".

This comment is a perfect example of how Argus just doesn't get it.

The role of directors is to protect the interests of shareholders (from a technical legal perspective, directors owe a duty to the company). In reality, directors essentially do two things: appoint the most senior executives, and sign off on significant corporation actions. Company directors and executives are stewards of the assets of a company -- they are supposed to act on behalf of shareholders to ensure that capital is allocated most effectively. It is the shareholders who own those assets, not the directors or executives.

For example, if a shareholder wants to buy shares in BHP Billiton, they would do so because they want exposure to the assets owned by BHP. These assets have been built over more than 100 years, using capital contributed by shareholders. If a shareholder in BHP is unhappy with how the board remunerates its executives, it is their right (and perhaps even their obligation) to do something about it. For someone such as Don Argus (who is paid very well by shareholders) to then say that shareholders should not complain about corporate governance issues, but instead "buy another company" indicates that he has grossly confused the role played by directors.

Moreover, Argus certainly isn't the right person to be taking aim at shareholders.

As Stephen Mayne pointed out in Crikey last week, Argus has been responsible for some of the most generous remuneration packages paid to poorly performed executives. Keith Lambert, who blew up hundreds of millions at Southcorp was paid more $6 million while Argus was a director. CK Chow, former head of Brambles, walked away with more than $4 million. While Chow was CEO of Brambles, the company lost hundreds of millions of dollars after literally losing 15 million pallets. According to the Australian Shareholders Association, during his time as CEO, Chow was paid lucrative performance bonuses, despite "not achieving a single strategic or financial objective".

But Argus' failures weren't limited to poor choice and overpayment of executives. Argus himself was head of NAB when it decided to purchase a US mortgage company called Homeside. Homeside ended up costing NAB almost $4 billion.

And that wasn't the worst of it. While chairman of BHP, Argus oversaw the transfer of literally tens of billions of wealth away from BHP shareholders, when he led the company into a merger with Billiton.

As part of the merger, BHP gave 43% of its assets, in exchange for Billiton's assets. The problem was Billiton's assets barely make any money where as BHP's are a veritable gold mine (the including coal, iron ore, copper and oil). Thanks to Argus, BHP shareholders have seen around $40 billion of their wealth transferred to Billiton shareholders.

This is more than 10 times as bad as HIH or ABC Learning.

Argus doesn't like investors taking action to protect their own interests because more than any other, he has been responsible for destruction of shareholder wealth and grotesque overpayment to poorly performed executives. In terms of shareholder returns, it seems that the sooner Don Argus fades away from the Australian corporate scene, the better.