Search

Recent comments

- brics.....

2 hours 55 min ago - nuke fukus.....

7 hours 4 min ago - dead or alive?....

7 hours 14 min ago - who what when where?....

8 hours 50 min ago - elon vs kanbra.....

9 hours 44 min ago - tanked think-tank.....

10 hours 45 min ago - (PAUSE)....

11 hours 11 min ago - repeat....

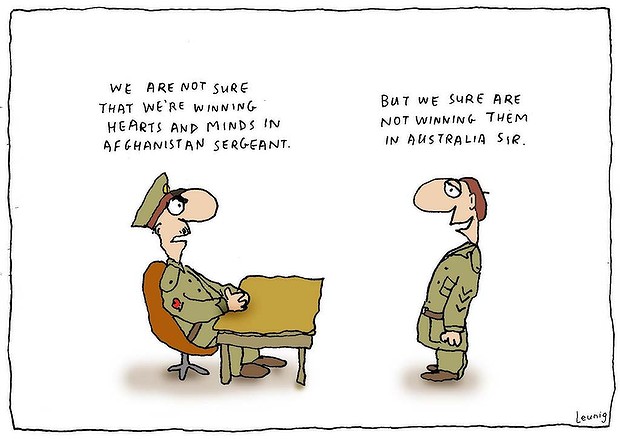

12 hours 4 min ago - losing....

12 hours 30 min ago - was Pepe sold a pup?....

13 hours 7 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

dying in vain .....

speech in support of wikileaks & against 11 years of war in Afghanistan ….

This month is the 11th anniversary of the Afghan war, a disastrous conflict that has achieved nothing more than destruction for Afghans and foreigners.

Yesterday Sydney’s Stop the War Coalition held a rally to mark this anniversary as well as supporting Wikileaks and Julian Assange in their struggle to tell the truth about Afghanistan, via the Afghan War Logs. I was one of the speakers. Below are my remarks (video begins at 26.20) and my notes:

· Since 2001 in Afghanistan, at least 2000 US soldiers have died.

· 2.4 million US soldiers have served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

· Almost 100,000 US war veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan were treated for post-traumatic stress disorder in 2011 alone.

· Unknown numbers of Afghan civilians killed.

· Reality on ground in Afghanistan, little infrastructure, intense fighting, huge civilian casualties, empowering of warlords, Taliban emboldened, very few girls have been educated.

· This is the war we’re told by our leaders is worth fighting.

· Strong impression when I was in Afghanistan this year was sheer futility of it all, profound ignorance expressed of what the West was doing there and who we’re fighting.

· This is what WikiLeaks’ Afghan War Logs showed us, the secret war, the war our leaders don’t want us to see.

· Why I’ve supported Wikileaks since its inception, 6 years ago this month, in October 2006.

· Today Julian Assange is right to resist extradition to Sweden. He’s right to fear the US. He’s an “enemy of the state”, akin to an al-Qaeda terrorist or the Taliban insurgency.

· Today we’re all “enemies of the state”, defending an organisation that shames most media outlets. Too few journalists in my profession speak out in support of Wikileaks, preferring to mock Assange.

· Where’s the accountability of politicians or journalists who backed Afghan war and demonised WikiLeaks for daring to tell us the truth?

· 11 years of lies about Afghan war and we’ll be leaving the country in 2014 in a complete mess. We owe the Afghan people financial compensation for destroying their country.

· Australian government must support Assange in his search for justice and as citizens we must demand the end of the Afghan war now plus hold our elites responsible for launching it.

· WikiLeaks is model of collaborative journalism and civic democracy.

Antony Loewenstein

and from the monthly ….

A price too high: It's time to cut and run ....

From January 2010 to January 2011, I was the National Commander of Australian defence forces in what our military refers to as the Middle East Area of Operations. I was responsible for a portion of the globe slightly larger than Australia, but almost all my energy was focused on one blighted province, Uruzgan, within a country beset by war for generations – Afghanistan.

I went to Afghanistan optimistic. I was sure that our military campaign to defeat the Taliban and to help to train the Afghan army was both right and achievable. When I left a year later I was crushed by sadness at the loss of too many good men, disheartened by the incompetence and corruption of the Afghan government, and fearful that all the blood and tears expended there would be wasted.

Eighteen months later, the situation hardly appears better. The Afghan government is as ineffective as ever, the Taliban remains a serious threat to security and now our troops confront a disturbing threat from within the ranks of the Afghan soldiers they are trying to train. Yet we are approaching the end game, when the international community departs, weary and bloodied, and we pass security responsibility to the fledgling Afghan National Army.

As I write these words, 38 Australian troops have been killed in action, and more than 240 wounded. For this expenditure, our soldiers have fostered the growth of the 4th Brigade of the Afghan National Army – the people we are training. Our special forces have significantly disrupted insurgent networks in Uruzgan and neighbouring provinces. Security is still poor but it’s better than it was. Some of the people of the province have an improved quality of life. I wonder, though, whether anyone in Afghanistan will thank us when all is said and done, or even remember our sacrifice.

Many Australians, including our politicians, forget that we are only minor players in the Afghanistan experiment, no matter how admirable the efforts of our troops and aid workers in Uruzgan. The country is a basket case, riven by tribal and ethnic enmity, prey to the criminality associated with being the world’s number one opium producer, and plagued by dysfunctional governance.

Australia cannot significantly influence the wider problems afflicting the government and people of Afghanistan. It beggars belief that Hamid Karzai, the bent and ineffectual president, could unite and lead the country if his illegitimate government were not propped up by the West. We are repeatedly told that the Afghan army will soon be ready to control the country on its own. But despite tremendous efforts by coalition trainers it remains a force lacking quality leadership, in possession of only basic equipment and skills, and poorly motivated. It is highly unlikely that the Afghan police service, intimidated by the Taliban and undermined by corruption and poor discipline, will ever bring law and order to backwaters like Uruzgan. Afghanistan still has one of the world’s highest infant mortality rates, an abominably low life expectancy, appalling levels of illiteracy, chronic health problems, and the fate of Afghan women and girls remains one of subjugation and disentitlement. In many ways, an active insurgency is the least of Afghanistan’s problems.

Also, there is no prospect that Pakistan will stop harbouring and supporting the Taliban any time soon. A Pakistani general in the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, the infamous ISI, once said to me, “Pakistan and Afghanistan will still be neighbours long after the international community has had its fill and leaves. The Taliban will also still be there when you all go home.” I think he’d probably know.

The Taliban know it too. Inevitably, the Afghanistan government must reach an accommodation with the Taliban. It is even possible that parts of the country, including our little patch in Uruzgan, will end up under some kind of semi-autonomous Taliban control along with the rest of the Pashtun ethnic area straddling southern Afghanistan. There will be no happy ending.

Whichever way it goes, Afghanistan’s destiny is beyond our control. So why stay? We could tie ourselves up there for years, spend more lives and a lot more money, for little profit. We’ve made a difference in one small corner of the country at great cost, but now would be a good time to leave, right? The problem is that we’ve made a hash of our strategy in Afghanistan and strangled our options for a dignified departure.

The goal of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) has drifted from defeating the Taliban – again – to nation building and democratisation. Our piece of the pie has evolved into training a brigade of the Afghan army based in Uruzgan, firstly in concert with the Dutch and later with the Americans. If we really have to be there, and putting aside the poor material we have to work with, this sounds like a reasonable pathway.

But now Australia is to assume leadership in Uruzgan, sometime in October. When I first heard this a few months ago, I thought it was a good idea. After all, I lobbied for just such an outcome when I was the national commander in Afghanistan back in 2010. But I was mistaken – it’s no longer a good idea, because the timing is wrong.

We could have assumed leadership in Uruzgan in 2010, when the Dutch withdrew.

Australia was repeatedly asked by ISAF generals and diplomats to take over the lead role from the Dutch, but our government wasn’t interested. Indeed, during my negotiations with the ISAF commander, General Stanley McChrystal, I was forcefully instructed by my Australian masters to give no hint that we might even consider it. But Australia’s position made no sense, strategically or tactically.

Strategically, our coyness damaged our reputation. Senior coalition officers and diplomats within the ISAF openly expressed their dismay at Australia’s refusal to lead. One prominent American officer referred to us as the “French of the South Pacific” – now, that stings.

At the tactical level, Australia’s objections included the assertions that we didn’t possess and couldn’t afford the combat-support units that the lead nation might be expected to provide. Yet I was told repeatedly that the US would underwrite us if we took the lead – such was the desire for Australia to raise its flag over the provincial headquarters. I dutifully transmitted all this up my chain of command back in Australia. They got it, but the politicians didn’t. The mantra was repeated: Australia would not take on leadership in Uruzgan. It was embarrassing to those of us on the ground.

Even the politics of it were illogical – our government told the electorate (and still does) that Australia has a vital national interest in helping to defeat the Taliban, and we would achieve this by training the Afghans. Yet, when asked, we weren’t prepared to take charge of the small multinational force in the province of Afghanistan where our combat troops were fighting, while training the locals. It seemed that political interests trumped vital interests.

Finally, after protracted and very difficult negotiations, the US took the lead of the headquarters in Uruzgan. Ironically, it was mostly made up of Australian officers.

Had we taken the lead role in mid 2010, we would have held a much more powerful hand in the game, with more options now. Leadership in Uruzgan would have brought more demands, but provided greater leverage with our coalition partners, more direct control of military operations, and enhanced our status with the Afghans.

Admittedly we did take charge of the provincial reconstruction team, but a dozen diplomats and aid workers hardly constitutes a major commitment. Two years on, we could have pointed to our record of leadership in the security and reconstruction realms as proof of our commitment to the coalition and the people of Afghanistan, and built a plausible narrative to support a phased withdrawal of our combat troops, starting now. We could already be welcoming home some of our troops.

Instead, we have encumbered ourselves with provincial leadership at precisely the time when we might have chosen to accelerate our departure, or at least have the option to do so. We have further entangled ourselves. Now it is impossible for us to withdraw our troops earlier than currently planned, regardless of the situation in Uruzgan. You can’t be a lead nation and not have a dog in the fight.

So we’re stuck, in a vice of our own making. We’re compelled to retain leadership of the multinational force in Uruzgan because reneging now would rightly open us up to being judged as a vacillating and unreliable actor in world affairs. By extension, we are also obliged to retain our conventional combat troops there until we depart at the end of 2013, when we will focus on institutional training at specialist schools. That’s another full year that our troops will be exposed to death and wounds in the valleys of Uruzgan and nearby provinces.

Some might argue that we need to finish training the Afghan soldiers. But what does ‘finished’ look like? It would take years, years, more training to get the Afghan army to a state of real competence. Our soldiers have done us proud by what they have achieved with the Afghan army’s 4th Brigade in Uruzgan. More training would obviously be helpful, but at some point there arises a situation of diminishing returns, where the risks of exposing our troops to danger exceed the potential benefits. We’re at that point now. Our posture over the coming year should be one of sharply reducing the danger for our troops. If that means we end up with a slightly less proficient 4th Brigade, that’s OK. If we offend some Afghan soldiers by keeping our distance, even inside patrol bases, that’s OK too. Let’s do the job on our own terms, at the least risk. I would defy anyone to spot the difference in the quality of the Afghan army a year or two after we depart. After all, it’s not a permanent force: recruits will often join and leave the army after a few years.

The reader might wonder why a military man like myself, a combat commander and all that hairy-chested stuff, would propose such a risk-averse posture. It’s because there is absolutely nothing in Afghanistan worth dying for, apart perhaps the act of saving another Australian’s life. Thirty-eight deaths are enough. I say this because I have seen, firsthand, what our war in Afghanistan costs.

I have looked into the faces of men, most of them barely in their 20s, who saw their mates struck down by bullets or blown apart by a homemade bomb. I have shared the misery of a young combat medic who fought in vain to save the life of a fellow digger bleeding into the dust. I have seen hardened men – special forces soldiers with more guts than the whole of our tawdry parliament combined – unable to speak as they shed tears for a lost friend. I have held the hands of critically wounded men in intensive care units, their bodies torn, their limbs ruined, their lives changed forever. I have stood in the harsh fluorescent light of a morgue and placed my hand on the cold bodies of fallen soldiers to say goodbye, before loading them into the belly of aircraft taking them home to shattered families. In the Afghan summer of 2010 I did this ten times – ten miserable times.

Some will argue that the men and women we send to war are all volunteers who know the risks and take them willingly. Others will say that casualties are the unavoidable cost of doing business in a combat zone. There is an argument that says the lives of a few sometimes need to be expended for a greater good. Another line of reasoning takes the grand strategic view of international affairs, putting the case that Australia – a minnow in terms of military might, albeit a well-trained and reasonably equipped one – has no choice but to maintain strong bonds with a large and powerful friend, the US. And that friendship and protection sometimes demand reciprocal payments, in the form of going to war and spending some lives.

These arguments only work at the intellectual level. They do not make sense at the human level, at which every life is precious, where each dead soldier is someone and not just a number. The men who have died in Afghanistan had parents, sisters, brothers, partners and children who loved them. They had all lived and had an expectation of more living to come. How could any of these lives be considered forfeit? What measure of success of our campaign in Afghanistan could possibly warrant the grim procession of dead men that I supervised in 2010, and which has continued since?

Of course, the extraordinary men and women of the Australian Defence Force will always do what is demanded of them and if that includes dying in Afghanistan, they’ll do it. I know, absolutely, that the men who died in Afghanistan were doing what they loved, with mates they respected. I remain deeply humbled by their courage and sacrifice. But the price they have paid for progress in that distant, alien land is far too high.

Despite the tired platitudes offered by the prime minister and her disenchanted defence minister about “staying the course” in Afghanistan, it is impossible to justify any of the Australian lives already lost in Afghanistan and those that may yet come. This assessment acknowledges but disdains the international power politics and national self-interest that got us into Afghanistan. No life is worth what we have achieved in Afghanistan and hope to leave as our legacy. The unpitying mountains of Afghanistan have watched the dust of that harsh, beautiful country absorb too much blood already. Let’s do what we said we’d do, at minimum risk to our troops, as soon as possible, and then get the hell out.

John Cantwell

- By John Richardson at 8 Oct 2012 - 1:27pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a solemn reminder indeed ....

Australia has lost another soldier, the 39th Australian Defence Force soldier to have been killed in Afghanistan since 2002.

Defence Minister Stephen Smith described the fallen digger as a 24-year old "brave, young, Australian soldier".

The special forces soldier was killed by an improvised explosive device while on a partnered mission with Afghan forces in the bordering areas of Oruzgan Province.

The solider was killed instantly while clearing a compound. No other Australian or Afghan personnel were killed or injured in the explosion.

Chief of the Defence Force General David Hurley offered his "deepest sympathy" to the soldier's family, friends and ADF mates.

While the family of the soldier have asked that his personal details and service record is not yet released, the soldier was described as highly qualified and with operational experience.

His commanding officer described him as "an exceptional soldier who will be remembered as genuine, honest and dedicated".

General Hurley said the incident was a "solemn reminder of the dangers our servicemen and women face in Afghanistan each day".

The mission was conducted to disrupt an insurgent network. As it is still ongoing, General Hurley said he could not provide any further details about the location.

Australia currently has about 1550 troops deployed to Afghanistan.

In August, the ADF suffered its darkest day since the Vietnam War when it lost five soldiers in two separate incidents. This included two soldiers in a helicopter accident in Helmand Province and three soldiers in a "green on blue" attack north of Tarin Kowt.

This comes as Australian troops prepare to withdraw from Afghanistan, as part of a broader transition from international to Afghan forces.

While special forces - commandos and the SAS - will continue to undertake missions, all Australian regular troops are preparing to vacate the many small bases they have occupied, and in many cases built, in recent years by the start of next year.

Soldier Killed In Afghanistan

endgame ....

Kabul-watchers are rightly worried about what the withdrawal of Western aid money will mean for one of the most impoverished countries on the planet. But everyone's asking the wrong questions.

Afghanistan is awash in foreign aid. In 11 years of war, the United States and its allies have funnelled hundreds of billions of dollars into the country. As a result, international spending is now the biggest part of the economy, making Afghanistan an "extreme outlier" when it comes to aid dependency, according to the World Bank. In 2010, for example, it received about $15.7 billion in development funding alone. That's roughly equivalent to Afghanistan's entire gross domestic product. And with $9.4 billion in public spending versus $1.65 billion in revenues in 2010-11, the country is heading off a fiscal cliff as the international community scales down its involvement ahead of transition in 2014.

But what will be the political consequences of the money running dry? For the time being, international spending has forged a bought peace in Kabul, but many of the political settlements that keep violence at bay -- the agreements and expectations negotiated between elites -- could be upended by the transition.

To benefit from aid largesse, Afghans have had to cooperate. At the Kabul Bank, for instance, which was linked to major Afghan contractors employed by the United States and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), cooperation between competing factions enabled nearly $1 billion in insider loans to be siphoned off in recent years. The bank's financial arrangement illustrates the reigning political settlement in the country, uniting a number of national-level networks, most notably those of President Hamid Karzai, a southern Pashtun, and Vice President Mohammed Fahim, a northern Tajik. The Karzai-Fahim alliance has been crucial to stabilizing relationships between north and south in Afghanistan, and has been underpinned by the flow of international money, which provided an incentive to play along with the existing order.

This situation is replicated in hundreds of smaller, localized political agreements across Afghanistan. The country remains fragmented among rival networks of strongmen, many of whom have been co-opted by the central state and the international community. A drastic decline in funding will undoubtedly generate instability as the reigning political deals are renegotiated. Yet, even as the international community charges ahead with its exit strategy of increasing local troop levels and building bureaucratic capacity, there has been little serious analysis about the way its spending is interlinked with Afghan politics.

This week, I published a paper on Afghanistan's private security companies (PSCs) that examines the relationship between international spending and Afghan politics. Fed by the military surge, the PSC industry in Afghanistan has grown to a monstrous size, with high-end estimates of 60,000-80,000 employees in 2011, most of them armed Afghan guards.

Unlike Iraq, the PSC industry in Afghanistan is largely dominated by Afghans, and as result it has become deeply interlinked with the Afghan government and local politics. Many of the newly rich PSC owners were former commanders who fought in the Soviet and civil wars and were able to mobilize networks of armed men. Some of them, like Matiullah Khan in the province of Urozgan, have become the preeminent strongmen in their areas as a result of their control over supply convoy and base defense contracts for the United States and NATO.

The PSC industry is one example of how international funding, by its sheer scale, has shaped the environment in which Afghan actors make decisions. As such, it has a lot to say about the frequently bemoaned corruption of the Afghan central government.

Take, for example, the critical southern province of Kandahar, where in 2001, the Karzai family was faced with the task of outmaneuvering its principal rival, Gul Agha Sherzai, who had from the beginning secured crucial access to U.S. military patronage. Because of his contracts with the U.S. military -- which allowed him to transform his private militias into "legitimate" PSCs -- Sherzai was initially beyond the control of the central state. But President Karzai eventually outmaneuvered him by empowering his half-brother Ahmed Wali to take control of critical contracting networks, by making patronage appointments, and using the muscle of the central government to intervene directly in private business in Kandahar.

The result was politically beneficial for Karzai, but detrimental to Afghanistan's fragile democratic institutions. The corruption of the central government, in other words, was a product of the structure and scale of the international intervention, which made contracting, not institutions, the determinant of political power in Afghanistan.

So far, the myriad donor nations, militaries, and non-governmental organizations involved in Afghanistan have mostly defined a successful transition as a technical exercise - one defined by objectives like handing over security responsibilities to Afghan forces, enhancing the capacity of the civil service, and so forth. But the future stability of the country has less to do with Afghan troop levels than it does with whether Afghan powerbrokers can forge a more stable, indigenous order after the international money dries up.

There is, perhaps, a silver lining to the coming economic decline: Afghan politicians will have to rely more on their own people and less on a top-down flow of dollars. But the reckoning will not be pretty.

Afghanistan's Fiscal Cliff