Search

Recent comments

- waste of euros....

9 hours 34 min ago - macron l'idiot....

11 hours 19 min ago - pomp and charity....

11 hours 29 min ago - overshoot days....

11 hours 46 min ago - "americamaidan"

11 hours 58 min ago - australia sux....

12 hours 10 min ago - the little children....

12 hours 14 min ago - delayed food....

20 hours 5 min ago - free expression....

20 hours 27 min ago - macrolympicus....

21 hours 57 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

running-out of ammo ....

Whilst the opposition & self-appointed ‘defence specialists’ went into meltdown last week about the upcoming visit of US Secretary of State, Dillary Clinton, & Defence Secretary, Leon Panetta, & the alleged US ‘concern’ that Australia wasn’t ‘pulling its weight’ in the defence spending stakes (it wasn’t actually clear whether the issue was that we weren’t spending enough or whether we just aren’t spending enough on yankee stuff), a similar debate has broken-out in the home of the brave, now that the Presidential election is out of the way.

The following ‘opinion piece’ appeared in last week’s New York times & would seem to suggest that, given the suggestion that the US is about to ‘drive off a fiscal cliff’, unless it reins-in government expenditure, Dillary & friend will have a deal more to worry about in securing the interests of the US military-industrial complex than taking issue with the petty-cash coming from Australia.

In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower left office warning of the growing power of the military-industrial complex in American life. Most people know the term the president popularized, but few remember his argument.

In his farewell address, Eisenhower called for a better equilibrium between military and domestic affairs in our economy, politics and culture. He worried that the defense industry’s search for profits would warp foreign policy and, conversely, that too much state control of the private sector would cause economic stagnation. He warned that unending preparations for war were incongruous with the nation’s history. He cautioned that war and war-making took up too large a proportion of national life, with grave ramifications for our spiritual health.

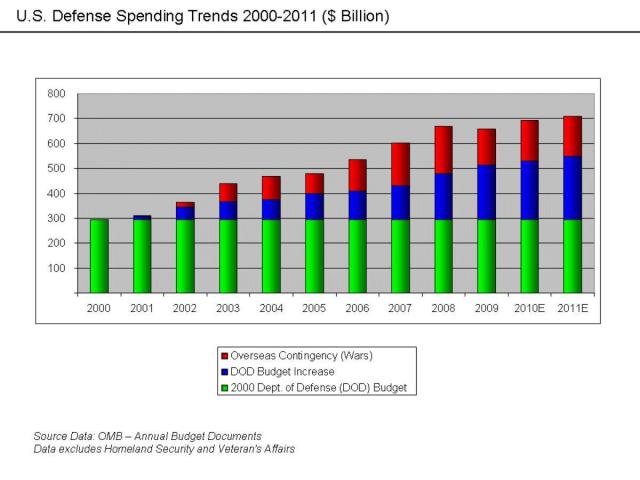

The military-industrial complex has not emerged in quite the way Eisenhower envisioned. The United States spends an enormous sum on defense - over $700 billion last year, about half of all military spending in the world - but in terms of our total economy, it has steadily declined to less than 5 percent of gross domestic product from 14 percent in 1953. Defense-related research has not produced an ossified garrison state; in fact, it has yielded a host of beneficial technologies, from the Internet to civilian nuclear power to GPS navigation. The United States has an enormous armaments industry, but it has not hampered employment and economic growth. In fact, Congress’s favorite argument against reducing defense spending is the job loss such cuts would entail.

Nor has the private sector infected foreign policy in the way that Eisenhower warned. Foreign policy has become increasingly reliant on military solutions since World War II, but we are a long way from the Marines’ repeated occupations of Haiti, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic in the early 20th century, when commercial interests influenced military action. Of all the criticisms of the 2003 Iraq war, the idea that it was done to somehow magically decrease the cost of oil is the least credible. Though it’s true that mercenaries and contractors have exploited the wars of the past decade, hard decisions about the use of military force are made today much as they were in Eisenhower’s day: by the president, advised by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Security Council, and then more or less rubber-stamped by Congress. Corporations do not get a vote, at least not yet.

But Eisenhower’s least heeded warning - concerning the spiritual effects of permanent preparations for war - is more important now than ever. Our culture has militarized considerably since Eisenhower’s era, and civilians, not the armed services, have been the principal cause. From lawmakers’ constant use of “support our troops” to justify defense spending, to TV programs and video games like “NCIS,” “Homeland” and “Call of Duty,” to NBC’s shameful and unreal reality show “Stars Earn Stripes,” Americans are subjected to a daily diet of stories that valorize the military while the storytellers pursue their own opportunistic political and commercial agendas. Of course, veterans should be thanked for serving their country, as should police officers, emergency workers and teachers. But no institution - particularly one financed by the taxpayers - should be immune from thoughtful criticism.

Like all institutions, the military works to enhance its public image, but this is just one element of militarization. Most of the political discourse on military matters comes from civilians, who are more vocal about “supporting our troops” than the troops themselves. It doesn’t help that there are fewer veterans in Congress today than at any previous point since World War II. Those who have served are less likely to offer unvarnished praise for the military, for it, like all institutions, has its own frustrations and failings. But for non-veterans - including about four-fifths of all members of Congress - there is only unequivocal, unhesitating adulation. The political costs of anything else are just too high.

For proof of this phenomenon, one need look no further than the continuing furor over sequestration - the automatic cuts, evenly divided between Pentagon and non-security spending, that will go into effect in January if a deal on the debt and deficits isn’t reached. As Bob Woodward’s latest book reveals, the Obama administration devised the measure last year to include across-the-board defense cuts because it believed that slashing defense was so unthinkable that it would make compromise inevitable.

But after a grand budget deal collapsed, in large part because of resistance from House Republicans, both parties reframed sequestration as an attack on the troops (even though it has provisions that would protect military pay). The fact that sequestration would also devastate education, health and programs for children has not had the same impact.

Eisenhower understood the trade-offs between guns and butter. “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed,” he warned in 1953, early in his presidency. “The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some 50 miles of concrete highway. We pay for a single fighter plane with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people.”

He also knew that Congress was a big part of the problem. (In earlier drafts, he referred to the “military-industrial-Congressional” complex, but decided against alienating the legislature in his last days in office.) Today, there are just a select few in public life who are willing to question the military or its spending, and those who do - from the libertarian Ron Paul to the leftist Dennis J. Kucinich - are dismissed as unrealistic.

The fact that both President Obama and Mitt Romney are calling for increases to the defense budget (in the latter case, above what the military has asked for) is further proof that the military is the true “third rail” of American politics. In this strange universe where those without military credentials can’t endorse defense cuts, it took a former chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Adm. Mike Mullen, to make the obvious point that the nation’s ballooning debt was the biggest threat to national security.

Uncritical support of all things martial is quickly becoming the new normal for our youth. Hardly any of my students at the Naval Academy remember a time when their nation wasn’t at war. Almost all think it ordinary to hear of drone strikes in Yemen or Taliban attacks in Afghanistan. The recent revelation of counterterrorism bases in Africa elicits no surprise in them, nor do the military ceremonies that are now regular features at sporting events. That which is left unexamined eventually becomes invisible, and as a result, few Americans today are giving sufficient consideration to the full range of violent activities the government undertakes in their names.

Were Eisenhower alive, he’d be aghast at our debt, deficits and still expanding military-industrial complex. And he would certainly be critical of the “insidious penetration of our minds” by video game companies and television networks, the news media and the partisan pundits. With so little knowledge of what Eisenhower called the “lingering sadness of war” and the “certain agony of the battlefield,” they have done as much as anyone to turn the hard work of national security into the crass business of politics and entertainment.

- By John Richardson at 11 Nov 2012 - 7:39pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

on well-oiled machines .....

from Crikey ….

Defence spending: the most expensive 'free ride' in history

BERNARD KEANE

AFGHANISTAN, DEFENCE COMPANIES, DEFENCE SPENDING, HILLARY CLINTON, WAR ON TERROR

One of the biggest disasters to befall the world's major arms companies was when, entirely without meaning to, the United States won the Cold War.

That victory was an appalling accident that not merely prompted dramatic cuts to defence spending, but deprived an entire generation of intelligence officers and defence officials of the excuse of an apocalyptic conflict to justify their behaviour.

The clash of freedom and communism, as it turned out, didn't quite measure up to the biblical loading it had received for so long, when our opponent was revealed as a hollowed-out bankrupt whose own controlling party was desperate to reform it.

To lose one excuse for running a Security State is a misfortune. To lose two is downright careless. Ever since, the United States has been struggling to devise a reason for continuing to support one of its most important industries. The War on Drugs did good duty for a time; the phrase "narco-terrorist" was coined and even that cool avatar of Cold War propaganda, James Bond, took on the cartels. But it was the War on Terror that provided the best excuse for reflexively ramping up military spending and encroaching on citizens' basic rights, not merely in the US but across the West.

The great appeal of the War on Terror is its self-perpetuating quality that guarantees this is one war where the danger of accidentally winning is slim: our invasion of Iraq proved a potent recruitment tool for terrorists, though not as much as Osama bin Laden hoped, while Barack Obama's remorseless drone war continues to outrage the communities targeted, particularly given a policy of follow-up strikes intended to kill emergency and rescue personnel.

Nonetheless, scarred by the terrible experience of the early 1990s, there is a continuing effort to identify looming threats that demonstrate the need for more defence expenditure and further restrictions on rights. Cyberwar, or cyberterrorism, the threat of the "digital Pearl Harbour"' is now a favoured plea of governments and corporations. And then there's China (a key part of the cyberwar threat, conveniently), a country that combines the ruthless dictatorial brutality of the Soviet Union at its worst with the intense spirit of capitalist competition the US knows so well.

All that is by way of laboured context for the debate that lurched back into life this week about Australian defence expenditure, including drawing two unlikely armchair generals in John Birmingham and Christopher Joye, both normally eminently sensible commentators, to call for an end to our "free ride" on the US military and, in Joye's case, the investigation of nuclear submarines. Can't wait to see backbenchers on both sides of politics putting their hands up to host a nuclear submarine base in their electorates.

If Australia is indeed free-riding on the US military, it has to be one of the most expensive free rides in history. As I showed in August, over the last decade Australian taxpayers have handed $22 billion to US defence firms for major procurement projects, including for some of the worst procurement debacles. Billions more have gone to the local subsidiaries of the big US firms, which employ plenty of Australians but funnel profits - often for standard consultancy, catering and maintenance services performed within Australian defence facilities - back to the US. Australia is deeply enmeshed in the US defence contracting industry, something sold to us as a boon but which often locks us into a narrow range of procurement options.

And those who complain that we're free-riding might like to go and ask the families of the 39 Australian soldiers killed in Afghanistan whether we're not paying any price for our reflexive support of the War on Terror.

These huge defence contractors are, in a very real sense, state-owned enterprises. They are run by former senior military officials, or former high-ranking intelligence and foreign affairs bureaucrats or well-connected politicians, many of whom circulate between such positions and public service. They rely heavily on US defence spending, and their overseas sales are facilitated by a vast government-run arms sales network that has representatives in scores of countries. They also act as vast cash-churning machines in Washington. Lockheed Martin has spent more than $22 million in lobbying in Washington in the last two years, and made $3 million in donations. Boeing has spent $24 million on lobbying and made over $2.6 million in donations; Northrop donated the same amount and spent $21 million on lobbying.

Lobbying will become more important for the big contractors because they face an enemy that may vanquish all attempts to confect threats justifying continued exorbitant defence spending: austerity. Cuts to US defence spending - which will be exacerbated by the fiscal cliff if no taxing and spending deal is done by Congress and the White House - are occurring at the same time as many other developed countries are slashing their defence spending. Indeed, US officials have already complained about cuts in other countries. Hillary Clinton publicly expressed concern at cuts by the new Tory UK government in 2010. Another conservative government, that of Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, earlier this year announced massive defence spending cuts to address Canada's budget deficit.

Conservative governments in the UK and Canada ripping into defence spending demolishes the suggestion that somehow cutting defence spending is a thing peculiar to Australia or to Julia Gillard. Compared to the cuts demanded by Harper, Gillard's austerity - primarily aimed at delaying or stopping overseas procurement - is innocuous.

Indeed, the most vociferous criticism of defence spending cuts has been directed at the US itself, with Mitt Romney unsuccessfully trying to make spending an issue of the Obama administration's own cuts in his presidential bid.

Spending cuts in all countries have been accompanied by a cacophony of complaint from former military officials, think tanks, foreign policy and defence institutes and defence commentators who form a potent cheer squad for the military-industrial complex, all of whom obsess about the themes of leaving freedom unprotected and failing to do the right thing by Our Boys. Oppositions usually join in too: one of the biggest critics of the UK spending cuts has been the Labour opposition.

Sometimes it's an odd fit given the conservative orientation of many commentators. Take The Australian Financial Review, for example: normally our most dependable foe of big government and industry protectionism, when it comes to defence spending The Fin is outraged at cuts to defence procurement expenditure and wants to see more taxpayer dollars being spent in our defence budget.

On defence spending, the government is only doing what virtually every other western government is currently doing, and for the same reasons. Indeed, compared to the likes of the US and Canada, the Gillard government's defence cuts looks like a trim and tidy-up. It could, and should, go a lot deeper. The only losers will be big US defence companies.