Search

Recent comments

- a testimony.....

2 hours 44 min ago - pirates of america....

4 hours 9 min ago - a 14-year old....

4 hours 26 min ago - a secular democracy....

9 hours 9 min ago - REVENGE!....

10 hours 17 min ago - replacing biden?

20 hours 12 min ago - realeetee.....

23 hours 7 min ago - rotten apple....

23 hours 15 min ago - is it true?.....

23 hours 23 min ago - "dangerous" words......

1 day 9 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

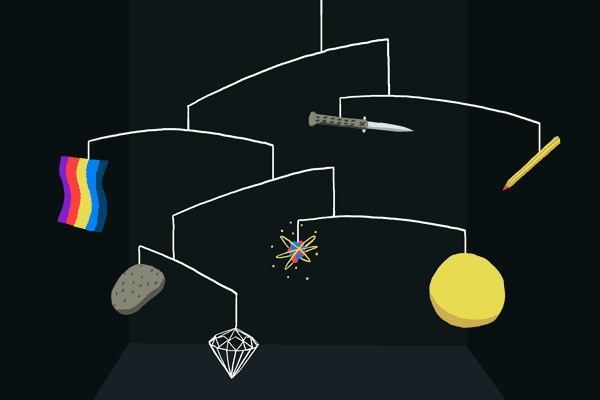

the old trolley dilemma .....

Moral quandaries often pit concerns about principles against concerns about practical consequences. Should we ban assault rifles and large sodas, restricting people’s liberties for the sake of physical health and safety? Should we allow drone killings or torture, if violating one person’s rights could save a thousand lives?

We like to believe that the principled side of the equation is rooted in deep, reasoned conviction. But a growing wealth of research shows that those values often prove to be finicky, inconsistent intuitions, swayed by ethically irrelevant factors. What you say now you might disagree with in five minutes. And such wavering has implications for both public policy and our personal lives.

Philosophers and psychologists often distinguish between two ethical frameworks. A utilitarian perspective evaluates an action purely by its consequences. If it does good, it’s good.

A deontological approach, meanwhile, also takes into account aspects of the action itself, like whether it adheres to certain rules. Do not kill, even if killing does good.

No one adheres strictly to either philosophy, and it turns out we can be nudged one way or the other for illogical reasons.

For a recent paper to be published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, subjects were made to think either abstractly or concretely - say, by writing about the distant or near future. Those who were primed to think abstractly were more accepting of a hypothetical surgery that would kill a man so that one of his glands could be used to save thousands of others from a deadly disease. In other words, a very simple manipulation of mind-set that did not change the specifics of the case led to very different responses.

Class can also play a role. Another paper, in the March issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, shows that upper-income people tend to have less empathy than those from lower-income strata, and so are more willing to sacrifice individuals for the greater good.

Upper-income subjects took more money from another subject to multiply it and give to others, and found it more acceptable to push a fat man in front of a trolley to save five others on the track - both outcome-oriented responses.

But asking subjects to focus on the feelings of the person losing the money made wealthier respondents less likely to accept such a trade-off.

Other recent research shows similar results: stressing subjects, rushing them or reminding them of their mortality all reduce utilitarian responses, most likely by preventing them from controlling their emotions.

Even the way a scenario is worded can influence our judgments, as lawyers and politicians well know. In one study, subjects read a number of variations of the classic trolley dilemma: should you turn a runaway trolley away from five people and onto a track with only one? When flipping the switch was described as saving the people on the first track, subjects tended to support it. When it was described as killing someone on the second, they did not. Same situation, different answers.

And other published studies have shown that our moods can make misdeeds seem more or less sinful. Ethical violations become less offensive after people watch a humor program like “Saturday Night Live.” But they become more offensive after reading “Chicken Soup for the Soul,” which triggers emotional elevation, or after smelling a mock-flatulence spray, which triggers disgust.

The scenarios in these papers are somewhat contrived (trolleys and such), but they have real-world analogues: deciding whether to fire a loyal employee for the good of the company, or whether to donate to a single sick child rather than to an aid organization that could save several.

Regardless of whether you endorse following the rules or calculating benefits, knowing that our instincts are so sensitive to outside factors can prevent us from settling on our first response. Objective moral truth doesn’t exist, and these studies show that even if it did, our grasp of it would be tenuous.

But we can encourage consistency in moral reasoning by viewing issues from many angles, discussing them with other people and monitoring our emotions closely. In recognizing our psychological quirks, we just might find answers we can live with.

Matthew Hutson, the author of “The 7 Laws of Magical Thinking: How Irrational Beliefs Keep Us Happy, Healthy, and Sane,” is writing a book on taboos.

- By John Richardson at 31 Mar 2013 - 6:50pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

we're happy like mice at a cheese fondue...

Some mice have to swim in the fondue should they loose their piece of bread, to retrieve it... Morality: morals are like cheese fondue... We know perfectly well that torture never delivers the result we're after (see Mr Masterman's work) and that torture turns us into sadistic nuts... We know that every time we drone someone, we also kill a few kids... "accidentally" of course... This tends to make sure the enemy does not start to weaken at the knees and stops hating us, does it? Because WHAT WOULD THE WORLD COME TO, if no-one I mean NO-ONE was hating us?... I mean hating the Yanks... This would mean that we'd have a soaring unemployment with soldiers in excess having to play cards like riot police in buses during down times... and bomb-factories becoming redundant...

I better stick to cheese fondue... Very popular in the 1970s... The rich mice dunk in the cheese with longer forks...