Search

Recent comments

- waste of euros....

8 hours 48 min ago - macron l'idiot....

10 hours 32 min ago - pomp and charity....

10 hours 42 min ago - overshoot days....

10 hours 59 min ago - "americamaidan"

11 hours 12 min ago - australia sux....

11 hours 23 min ago - the little children....

11 hours 28 min ago - delayed food....

19 hours 18 min ago - free expression....

19 hours 40 min ago - macrolympicus....

21 hours 10 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

from the ugly side of utopia .....

from john pilger …..

The Brutal Past and Present are Another Country in Secret Australia

The corridors of the Australian parliament are so white you squint. The sound is hushed; the smell is floor polish. The wooden floors shine so virtuously they reflect the cartoon portraits of prime ministers and rows of Aboriginal paintings, suspended on white walls, their blood and tears invisible.

The parliament stands in Barton, a suburb of Canberra named after the first prime minister of Australia, Edmund Barton, who drew up the White Australia Policy in 1901. "The doctrine of the equality of man," said Barton, "was never intended to apply" to those not British and white-skinned.

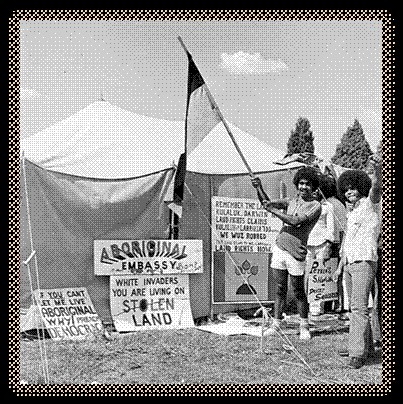

Barton's concern was the Chinese, known as the Yellow Peril; he made no mention of the oldest, most enduring human presence on earth: the first Australians. They did not exist. Their sophisticated care of a harsh land was of no interest. Their epic resistance did not happen. Of those who fought the British invaders of Australia, the Sydney Monitor reported in 1838: "It was resolved to exterminate the whole race of blacks in that quarter." Today, the survivors are a shaming national secret.

The town of Wilcannia, in New South Wales, is twice distinguished. It is a winner of a national Tidy Town award and its indigenous people have one of the lowest recorded life expectancies. They are usually dead by the age of 35. The Cuban government runs a literacy programme for them, as they do among the poorest of Africa. According to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth report, Australia is the richest place on earth.

Politicians in Canberra are among the wealthiest citizens. Their self-endowment is legendary. Last year, the then minister for indigenous affairs, Jenny Macklin, refurbished her office at a cost to the taxpayer of $331,144.

Macklin recently claimed that, in government, she had made a "huge difference". This is true. During her tenure, the number of Aboriginal people living in slums increased by almost a third, and more than half the money spent on indigenous housing was pocketed by white contractors and a bureaucracy for which she was largely responsible. A typical, dilapidated house in an outback indigenous community must accommodate as many as 25 people. Families, the elderly and the disabled wait years for sanitation that works.

In 2009, Professor James Anaya, the respected UN Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous people, described as racist a "state of emergency" that stripped indigenous communities of their tenuous rights and services on the pretext that pedophile gangs were present in "unthinkable" numbers - a claim dismissed as false by police and the Australian Crime Commission.

The then opposition spokesman on indigenous affairs, Tony Abbott, told Anaya to "get a life" and not "just listen to the old victim brigade." Abbott is now the prime minister of Australia.

I drove into the red heart of central Australia and asked Dr. Janelle Trees about the "old victim brigade". A GP whose indigenous patients live within a few miles of $1,000-a-night resorts serving Uluru (Ayers Rock), she said, "There is asbestos in Aboriginal homes, and when somebody gets a fibre of asbestos in their lungs and develops mesothelioma, [the government] doesn't care. When the kids have chronic infections and end up adding to these incredible statistics of indigenous people dying of renal disease, and vulnerable to world record rates of rheumatic heart disease, nothing is done. I ask myself: why not? Malnutrition is common. I wanted to give a patient an anti-inflammatory for an infection that would have been preventable if living conditions were better, but I couldn't treat her because she didn't have enough food to eat and couldn't ingest the tablets. I feel sometimes as if I'm dealing with similar conditions as the English working class at the beginning of the industrial revolution."

In Canberra, in ministerial offices displaying yet more first-nation art, I was told repeatedly how "proud" politicians were of what "we have done for indigenous Australians". When I asked Warren Snowdon - the minister for indigenous health in the Labor government recently replaced by Abbott's conservative coalition - why after almost a quarter of a century representing the poorest, sickest Australians, he had not come up with a solution, he said, "What a stupid question. What a puerile question."

At the end of Anzac Parade in Canberra rises the Australian National War Memorial, which historian Henry Reynolds calls "the sacred centre of white nationalism". I was refused permission to film in this great public place. I had made the mistake of expressing an interest in the frontier wars in which black Australians fought the British invasion without guns but with ingenuity and courage - the epitome of the "Anzac tradition". Yet, in a country littered with cenotaphs not one officially commemorates those who fell resisting "one of the greatest appropriations of land in world history", wrote Reynolds in his landmark book Forgotten War. More first Australians were killed than Native Americans on the American frontier and Maoris in New Zealand. The state of Queensland was a slaughterhouse. An entire people became prisoners of war in their own country, with settlers calling for their extinction. The cattle industry prospered using indigenous men virtually as slave labour. The mining industry today makes profits of a billion dollars a week on indigenous land.

Suppressing these truths, while venerating Australia's servile role in the colonial wars of Britain and the US, has almost cult status in Canberra today. Reynolds and the few who question it have been smeared with abuse. Australia's unique first people are its Intermenschen. As you enter the National War Memorial, indigenous faces are depicted as stone gargoyles alongside kangaroos, reptiles, birds and other "native wildlife".

When I began filming this secret Australia 30 years ago, a global campaign was under way to end apartheid in South Africa. Having reported from South Africa, I was struck by the similarity of white supremacy and the compliance and defensiveness of liberals. Yet no international opprobrium, no boycotts, disturbed the surface of "lucky" Australia. Watch security guards expel Aboriginal people from shopping malls in Alice Springs; drive the short distance from the suburban barbies of Cromwell Terrace to Whitegate camp, where the tin shacks have no reliable power and water. This is apartheid, or what Reynolds calls, "the whispering in our hearts".

John Pilger's film, Utopia, about Australia, is released in cinemas on 15 November and broadcast on ITV in December. It is released in Australia in January.

Follow John Pilger on twitter @johnpilger - http://johnpilger.com

- By John Richardson at 7 Nov 2013 - 5:25pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

utopia ....

Australian journalist and BAFTA-award winning documentary filmmaker John Pilger has a strong investigative record spanning a 40-year career. In his latest film, Utopia, he turns his incisive hand to a topic integral to the Australian story, yet ostensibly glossed over by many of its own inhabitants – that of Indigenous Australia.

The devastating inequalities suffered by the Aboriginal community are revealed against a backdrop of the great mineral resources boom sustaining the economic prosperity of a population Pilger argues are indifferent to the apartheid culture it is sustaining. As Utopia premiers in the UK, John Pilger talks to Australian Times about our country’s forgotten past.

1. You have described the modern day situation of Indigenous Australians as a form of apartheid without acknowledgement – what do you think should be done to redress the situation?

Education and public debate are important, but the catastrophe imposed on Indigenous Australians is the equivalent of apartheid, and the system has to change. Colonialism in Australia has to end, finally. There has to be genuine political, social and moral restitution, and that means a treaty and universal land rights. By treaty, I mean a constitutionally binding ‘bill of rights’ for Indigenous people and recognition of their right to self-determination. This can only be achieved by negotiation between the majority and minority populations on an equal basis. Australia is the only western country with an Indigenous population that has no treaty: no framework of mutual respect. Before anything can change, that must change.

2. Indigenous Australians have the lowest life expectancy of any of the world’s Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous men are incarcerated at eight times the rate of apartheid South Africa in Western Australia, which is home to the current “resources boom”. What is the connection between the “resources boom” and the situation of disadvantage experienced by the Indigenous population?

As Dave Sweeney of the Australian Conservation Foundation says in my film, the mining companies exploit land they don’t own and extract riches that are not theirs. Indigenous Australians have a right to share in the so-called resources boom, or to veto the destruction and desecration of land. At present, a few Aboriginal land corporations have benefited, but most communities remain impoverished. Native Title – hailed as an advance by white Australia – has allowed the mining companies to dig up Indigenous land almost as they please, and without fearing an Indigenous veto

3. Can Australia’s need (or want) for mineral resources, and respect for Aboriginal land rights, ever coexist?

Yes, of course. A modern, civilised society shares its resources, not hands them to Gina Rinehart.

4. Tony Abbott has appointed the chairman of Fortescue Metals Group, Andrew Forrest, to run a review of Indigenous training and employment programs and provide recommendations aiming to connect unemployed Indigenous people with “real and sustainable jobs”. Do you think this review will be able to provide any meaningful recommendations?

No. There have been umpteen “reviews”. The facts are well known. This is like asking the fox to review the state of the chicken pen. It’s not serious and reflects the new prime minister’s archaic view of Aboriginal people.

5. Mr Forrest says his own company has a training program to provide Aboriginal people with employment – is this one way mining companies can work with the Aboriginal communities to address inequalities?

No. Andrew Forrest’s only claim to this authority is his wealth. His “training program” is shrouded in public relations and the number of jobs claimed is disputed. The matter of jobs and training should be a public – that is, government – initiative following consultation with Aboriginal people — such as, for example, the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation, which has a great of experience dealing with Fortescue.

6. How can profits from the resources boom be better directed towards assisting Indigenous Australians?

Tax them and pass on the revenue in basic infrastructure, such as housing. The abandonment of the Labor government’s ‘super tax’ on mining profits lost the nation an estimated $60 billion – enough to pay for land rights and end Indigenous poverty.

7. You first reported on the situation of Australia’s Indigenous population for The Secret Country (1985) and then in three subsequent films. Why is this topic of particular importance to you?

I am an Australian who grew up, like most Australians, with a head full of myths about Aboriginal people. As a journalist and film-maker, I have a duty to attempt to help tell the truth about an extraordinary, brutalised people who provide Australia’s derivative society with its uniqueness.

8. Do you feel anything has changed in the last 30 years?

Some things have changed. A small Indigenous ‘middle class’ has been largely co-opted by white Australia, telling the politicians and the media what they want to hear. What hasn’t changed is the cynicism of the Australian political elite towards the First Australians, together with an almost wilful indifference in the majority population. Australians often refer to themselves as ‘lucky’; and they’re right. One aspect of this ‘luck’ is that the world has taken so long to cotton on to Australia as an apartheid state.

9. You have said documentaries can “reclaim shared historical and political memories, and present their hidden truths.” Is your intention with Utopia to achieve this for Indigenous Australians?

Yes, that’s one aim of Utopia. Another is to demonstrate to majority Australia that there is no longer an ‘out’ on this issue. The excuses have dried up. Until Australians restores true nationhood to the Aboriginal people, they can never claim their own.

damning high rate of incarceration of Indigenous people...

In terms of infrastructure, Australia is a developed nation. We have a (mostly) affordable healthcare system, access to effective medical intervention and a welfare system that, while imperfect, is still more comprehensive than many other countries. So why do we still hear stories of people who have been so grossly failed by the system that they have become casualties to it?

Last week, the compassionate among us were rocked by revelations that an asylum seeker imprisoned on Manus Island had lapsed into a coma which rendered him brain dead after a cut on his foot was left untreated and became septic. A cut. In response, vigils were held where citizens called once again on the government to apply some basic humanity to the treatment of asylum seekers.

And yet, this despicable disregard for human lives deemed less worthy as a result of Australia’s institutionalised racism is not limited to those unfortunate souls who have the temerity to seek safety on our shores. Just over a month ago, a 22 year old woman in Port Hedland died while in police custody. Her crime? Ostensibly, the failure to pay a $1000 fine.

But maybe it was also just that she was Aboriginal.

In early August, the young Yamatji woman (whose name we will refer to only as ‘Miss Dhu’ and whose photograph we will not publish in accordance with her family’s wishes) was incarcerated for four days alongside her partner for failing to pay a fine. In WA, recipients of fines can elect to pay them off in custody at a rate of $250 a day, a policy which the shadow Aboriginal Affairs Minister Ben Wyatt believes helps to maintain the persistently high rate of incarceration of Indigenous people while failing to address the underlying issues which might lead to this.

And so it was that Miss Dhu ended up police custody. Despite complaining early on of experiencing severe pain, vomiting and even partial paralysis (which may have been as a result of a septic infection relating to a blood blister on her foot acquired prior to her arrest), Miss Dhu was twice released from the local Hedland Health Campus after being deemed fit to return to the watchhouse. Incredibly, it has been reported that these decisions were made despite Miss Dhu not being seen by a doctor in either visit. Her partner Dion Ruffin has alleged that as she grew increasingly sicker, police laughed and accused her of acting. Around midday on August 4, Miss Dhu made her final visit to the Hedland Health Campus while in a ‘near catatonic state’.

Shortly after, she was pronounced dead.

read more: http://www.dailylife.com.au/news-and-views/dl-opinion/you-should-know-her-name-miss-dhu-was-aboriginal-22-and-died-four-days-after-being-in-custody-20140908-3f2zz.html