Search

Recent comments

- crime against peace....

1 hour 54 min ago - why is Germany supporting the ukrainian nazis?....

3 hours 6 min ago - sanctioning....

5 hours 50 min ago - politico blues....

6 hours 30 min ago - gender muddles....

6 hours 50 min ago - war crimes and war crimes....

9 hours 39 min ago - new yourp....

10 hours 19 min ago - piracy not included....

10 hours 48 min ago - faceblock......

12 hours 45 min ago - 22-......

13 hours 51 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

of patents and socialism...

Throughout the ages, especially since the industrial revolution, patents have prevented social development. I know — this is a bold relative statement which demands some clarification.

When someone invents or discovers something, there is a proprietary concept attached to this. It's a bit like a king conquering new lands: it's mine. The idea that this can be counter-productive to the entire social moire is controversial, despite some improvements to the natives' ways of life under the gun and missionary conversion. By this I mean should someone invent a new engine, this new engine can be beneficial to the society at large but the patent prevents anyone else to improve upon the idea and this can be retrograde — or at least limiting.

This is why, in the 1920s, most grand scientific discovery and theories about the atomic age about to be unleashed through quantum mechanics were genuinely shared through symposiums and public knowledge. This is why someone like Einstein preferred socialism to capitalism. He preferred sharing to hogging.

Imagine that Mr Watt invents a steam engine. He patents it (1781). No-one can improve on it for twenty years, except himself. But he did not invent the steam engine. He improved the steam engine of a certain Mr Newcomen who had "not patented" his own work (1712), after he himself had improve the "first practical atmospheric pressure steam engine of Thomas Savery patented in 1698. Soon after Bento de Moura Portugal had also improved on Savery's engine.

The main improvement from Mr Watt was to find a way to convert reciprocating movement into rotary motion. Easy. The leg on the pedals of the bicycle so to speak... plus the angular momentum of a big heavy wheel...

In the first century AD, Hero of Alexandria had already "invented" rotary motion using steam powered jets, for demonstration purpose. Even in 1551, a steam turbine was active and Jeronimo de Ayanz y Beaumont had 50 patents of steam powered inventions that were used to pump water out of mines. In 1679, Denis Papin used a steam driven piston to lift heavy weights.

In his youth, Gus created many aeolipiles in the spirit of Hero of Alexandria. The contraption is simple. have a suspended water boiler on a swivel, a couple of jets pouring from it through bent pipes, a candle or a hexamine (1,3,5-Trioxane, hexamethylenetetramine) tablet on fire and you get a spinning device which you can decorate with planes, rockets, fairies or angels. Great amusement for kids, but don't touch the steam coming out. It's scolding hot. Once you know that, you can watch the thingster spinning until it runs out of steam in the boiler or the flame goes out... Hours of fun.

Soon with most invention, the development enters a phase where monopolising the industry becomes the centrepiece of trade. TTP — here we come... Undemocractic. We have seen this with computers, googling and the internal combustion engine fuel. Oil companies make sure that the combustion engine is our most used form of transportation energy source. Steam engine and electric engines have been struggling to make a dint on the market place, not by fault of trying or possible search of improvement, but since humans conquered fire, the call of the flame has been irresistible and, to say the least, oil is easier to control and sell.

We even burn coal, gas and oil (very inefficiently) to provide electricity...

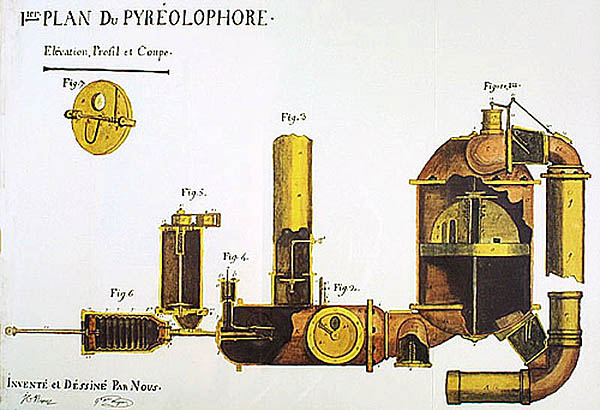

One of the first internal combustion engine was patented in 1807 by Nicephore Niepce, the French inventor of photography, and used to power a boat (pictured at top) — while François Isaac de Rivaz, a Swiss, powered an automobile in 1808 with a HYDROGEN burning internal combustion engine.

Here in 2016, we're going full circle with a "new" invention... The Russian hydrogen-powered drone. Drones have been the domain of model-plane making enthusiasts. They were not called drones, but model planes, the "droning" of which were coming from the two-stroke engines running on a castor oil/petrol/ether mix and some "pulso-reactors", akin to the V1 rocket engines, running on kerosene.

Now, "droning" has become a large industry, especially since the invention of powerful small lithium batteries and computerised equilibrium. But according to the Russian brochure (military), the hydrogen-powered (internal combustion engine) has a much greater autonomy than the electrically driven drone. All one needs for power is a small tank of hydrogen and a filter to eliminate the possibility of creating (dangerous) nitrous oxides in the process.

Here we are talking of SMALL drones, not the drones used by the US airforce which are plane-size drones with no pilots but plenty of bombs, and driven by brain-dead video-game addicts.

These smaller drones can cheaply deliver medical supplies or a dose of C4 into a nest of designated enemy.

For this, many other inventions had to be "miniaturised", like cameras, GPS and radio transmitters.

In Gus' days, radio-controlled model planes were rare and the equipment was bulky, using resonating blades or calibrated crystals responding to various frequencies of a weak radio signal. The same signal was used to perform various operations in sequence. One needed two or several receivers and transmitters to achieve better "instantaousness". for example in a single transmitter, for the unit to go left, one had to press the same button twice than for it to go right but it went left after the unit went right in the first place. Something to get used to.

Radio transmission was patented in 1872 by William Henry Ward, while in Germany, transmitted "oscillation" of radio-waves were studied by various characters around the 1850s.

In the late 1980s, Gus' expensive marine GPS was accurate to about 50 metres and its altimetrics was unable to know if one was travelling 400 metres above sea level or 20 metres below it. And it could only give coordinates in longitude and latitude which had to be looked up on a map.

We all take our GPS for granted these days but the gestation of the system could be one of the most complicated invention ever. In parallel with the US GPS, there has been the Russian GLONASS system and a bit later on, the European system.

The invention started with the need for calculating accurate instant location of whatever. The idea of using satellites to transmit data that could be used to locate a position by extrapolating source and angle of reception is quite ingenious. One major hurdle is that "time in space" for moving satellites is slightly different than "time on the surface of the earth". After a few minutes this becomes a MAJOR problem. This was of course well-expressed by our own Einstein in his mechanics of relativity. Here this problem had to be solved by compensating the "clocks" on board the satellites to artificially adjust to surface time.

Calculating longitude since the 16th century was always done by clocks and the problem has been to get clocks accurate enough. A one second inaccuracy equals about 1.5 mile of longitude error. It means the difference between going aground or staying afloat. Add an angular error of a couple of minute on the sextant observations and one is 120 miles off from where one should be. Maths here are approximated values only...

The GPS network and the GLONASS are accurate enough to land a matchstick on a matchstick at mach 1.5, but this is for military use only. In our cars, the system is limited to 10 metres accuracy update. Meanwhile cameras with pinhead-size lenses can take pictures of quality even never dreamed of by the new god of megapixels ten years ago.

So the miniaturisation of stuff has "revolutionised" the way we commit ourselves to the future, including bombing each others. Now, it's time to make sure than not one technology becomes exclusive to one nation or to one singular mad man. The only way to do this is via socialism and unpatented shared inventions — in which it can and should become easier to check for the bad side effects of the inventions, such as GMOs... The environmental equation would also be part of the assessment with the grading of inventions. At present it's not. We live in the dark. Unhealthy competition would be eliminated, though these processes would still "improve" for humanity, not just for a few rich pricks who could highjack inventions, for cash and power.

We need to spread the power, the research and the shit around, while minimising theft and maintain exclusion of technological access to crackpots, idiots and terrorists. Easier said than done. Good will is in short supply in the human brain. In this regard, the TTPs are terroristic anathema to the concept of democracy and are secretly concocted because they are reliant in a major part on greed and bad will.

Gus Leonisky

Your local mad inventor.

- By Gus Leonisky at 22 Jul 2016 - 3:20pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

sharing the planet...

Last month was the hottest June on record globally, new data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has confirmed.

June also marks the 14th consecutive month to break its temperature record, the longest such streak in NOAA's 137 years of record-keeping.

read more: http://www.climatecouncil.org.au/14-months-in-a-row-of-record-breaking-heat

a hydrogen car...

STEVE MANNING, a financial consultant in Southern California, liked the idea of driving a car that would go easy on the environment.

But last November, as he eyed a $58,000 Toyota Mirai at the dealership near his home in Santa Ana, he had to think more than twice.

This was not just any electric car. Its electricity comes from fuel cells powered by hydrogen, which means the only tailpipe emissions are water vapor. That would be good for the climate, but a logistical challenge for the consumer.

In Mr. Manning’s case the nearest hydrogen filling station was seven miles from his house. And the technology was still so new that there were fewer than a dozen others in the entire state.

“Is this really practical?” he asked himself. In the end, he took a leap of faith, agreeing to lease a silver Mirai for $499 a month. “I said, ‘If it sucks, it sucks,’” he recalled in a recent telephone interview.

He has no regrets. Because of a big push by the State of California to invest in a growing network of filling stations, he has never run out of fuel. Driving a hydrogen-powered car has proved a pleasant surprise to Mr. Manning and others in California’s small but growing cadre of owners of fuel-cell cars.

Like other electrics, the Mirai does not have a transmission and accelerates quickly from a stop. “I can burn rubber,” said Glenn Rambach, a retired engineer who bought one last fall.

http://www.nytimes.c#mce_temp_url#om/2016/07/22/automobiles/water-out-the-tailpipe-a-new-class-of-electric-car-gains-traction.html?_r=0

The first "hydrogen" powered car was built in 1808. 207 years ago. Read from top.

property is theft...

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (French: [pjɛʁ ʒɔzɛf pʁudɔ̃]; 15 January 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French politician and the founder of mutualist philosophy. He was the first person to declare himself an anarchist[1][2] and is widely regarded as one of the ideology's most influential theorists. Proudhon is even considered by many to be the "father of anarchism".[3] He became a member of the French Parliament after the revolution of 1848, whereafter he referred to himself as a federalist.

Proudhon, who was born in Besançon, was a printer who taught himself Latin in order to better print books in the language. His best-known assertion is that Property is Theft!, contained in his first major work, What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (Qu'est-ce que la propriété? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement), published in 1840. The book's publication attracted the attention of the French authorities. It also attracted the scrutiny ofKarl Marx, who started a correspondence with its author. The two influenced each other: they met in Paris while Marx was exiled there. Their friendship finally ended when Marx responded to Proudhon's The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty with the provocatively titled The Poverty of Philosophy. The dispute became one of the sources of the split between the anarchist and Marxist wings of the International Working Men's Association. Some, such as Edmund Wilson, have contended that Marx's attack on Proudhon had its origin in the latter's defense of Karl Grün, whom Marx bitterly disliked, but who had been preparing translations of Proudhon's work.

Proudhon favored workers' associations or co-operatives, as well as individual worker/peasant possession, over private ownership or the nationalization of land and workplaces. He considered social revolution to be achievable in a peaceful manner. In The Confessions of a Revolutionary Proudhon asserted that, Anarchy is Order Without Power, the phrase which much later inspired, in the view of some, the anarchist circled-A symbol, today "one of the most common graffiti on the urban landscape." He unsuccessfully tried to create a national bank, to be funded by what became an abortive attempt at an income tax on capitalists and shareholders. Similar in some respects to a credit union, it would have given interest-free loans.

read more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre-Joseph_Proudhon

altruism...

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857), better known as Auguste Comte(French: [oɡyst kɔ̃t]), was a French philosopher. He was a founder of the discipline of sociology and of the doctrine ofpositivism. He is sometimes regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.

Influenced by the utopian socialist Henri Saint-Simon, Comte developed the positive philosophy in an attempt to remedy the social malaise of the French Revolution, calling for a new social doctrine based on the sciences. Comte was a major influence on 19th-century thought, influencing the work of social thinkers such as Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill, and George Eliot.[5] His concept of sociologie and social evolutionism set the tone for early social theorists and anthropologists such as Harriet Martineau and Herbert Spencer, evolving into modern academic sociology presented by Émile Durkheim as practical and objective social research.

Comte's social theories culminated in his "Religion of Humanity", which presaged the development of religious humanist and secular humanist organizations in the 19th century. Comte may have coined the word altruisme (altruism).

read more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguste_Comte

Note: Comte's "metaphysical stage involved the justification of universal rights as being on a vauntedly higher plane than the authority of any human ruler to countermand, although said rights were not referenced to the sacred beyond mere metaphor."

a case in point...

In the patent battle royale over CRISPR, the revolutionary genome-editing tool, the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on 15 February won a critical round in its ongoing fight with the University of California (UC). But the UC researchers and their affiliated companies attempted to spin their defeat at the appeal board of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office as a victory of sorts as they now can pursue the issue of their CRISPR, which has been on hold since the “interference” proceedings against Broad began. At issue is whether Broad piggybacked on UC’s inventions when its researchers showed that CRISPR worked in human cells, which is critical for making new medicines. The appeal board said no, dismissing UC’s interference complaint. But the board did not rule on the actual claims made by each party, which leaves open the confusing possibility that UC will hold a patent for use of CRISPR in any type of cell and Broad will own the intellectual property to eukaryotic cells alone. Any way about it, companies that have licensed the technology are scrambling to figure out whom they have to pay fees to, and the uncertainly likely will continue unless UC and Broad can agree on a “cross-licensing” settlement that, in effect, shares the patent revenues. Patent experts continue to criticize the institutions for not striking a deal, and they also anticipate that there’s more litigation to come.

read more:

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/355/6327/786

read from top...

forgetting your pills...

Last June, a health care researcher in the United States was clearing out her email when she came across a message that looked like spam. She was about to delete it when a name in the subject line gave her pause: Dr. Morisky.

The message concerned an abstract that the researcher and two colleagues had published in a journal just days before. It asked whether the researchers had obtained a license for a copyrighted questionnaire, called the Eight-Item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), that they’d used in the study. The scale helps predict how likely patients are to adhere to a drug regimen—an important issue, because a lack of adherence can worsen health and is estimated to cost $300 billion a year in the United States.

The researcher, then a graduate student, says she had contacted the scale’s author, public health specialist Donald Morisky of the University of California, Los Angeles, for permission to use the tool. She never heard back. Now, Morisky and a colleague, Steve Trubow, were demanding $6500 for its use. Stunned, the researcher replied that she couldn’t afford that, but offered $200. The reply came about 3 hours later: “Unfortunately … we can’t reduce the fees. … We will turn this case over to our lawyer.”

read more:

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/09/pay-or-retract-survey-creators-demands-money-

Read from top...

patents and progress…….

BY David Gordon

Murray Rothbard rejected patents, and other writers, following and extending his views, have developed a wide array of arguments against patents in particular and intellectual property (IP) in general. Stephan Kinsella’s Against Intellectual Property is the most detailed and carefully argued of these studies. Not all of those inclined in a free market direction agree with this position, though, and in this week’s article, I’d like to look at some arguments in defense of patents found in Adam Mossoff’s article “Intellectual Property,” in The Routledge Companion to Libertarianism (pp. 471–85). The article sets out very well the main arguments for and against IP; and although Mossoff is a strong proponent of IP, which he defends from the standpoint of Objectivism, the article’s aim is to explain the arguments in the controversy rather than to defend his own position.

Opponents of patents say that you can’t own an idea, and Mossoff responds that in one sense, they are right.

If IP rights literally meant people owned ideas … then thinking about a patented invention or a copyrighted book would be patent or copyright infringement. But this has never been true: IP rights protect only real-world inventions, books, movies, songs, corporate logos, and commercial secrets by preventing unauthorized copies, sales, or uses of these products or processes. (p. 474)

Here a problem arises if, like Rothbard, you hold that people acquire unowned resources by appropriating them—i.e., by being the first to use them. This is a “Lockean” view, though to avoid problems pointed out by David Hume, among others, it is perhaps better to drop John Locke’s phrase that you acquire resources by “mixing your labor” with them. In this theory, it isn’t at all clear how arriving at a new idea, and making this public through a recognized process, would give you rights over a physical object. It’s interesting to note, though, as Mossoff points out, that Locke himself accepted patents (in effect) and copyright, though he did not know the former word; but in arriving at our own position, what is of interest is the essential truth, if truth it be, of the Lockean theory rather than the ipsissima verba of its inventor. Further, as Stephan Kinsella has pointed out to me, Locke did not take copyrights and patents to be natural rights.

Mossoff would respond by rejecting Lockean theory. If, as I think we can, we attribute to him the views he ascribes to Ayn Rand, Mossoff would argue in this way:

Although Rand’s justification for property rights is often associated with Lockean or natural rights, it is distinct from it in several respects, such as her unique concept of “value” and her insight in creating and using values … Rand justified IP rights as “the legal implementation of the base of all property rights: a man’s right to the product of his mind.” (p. 477)

In Rand’s usage, a “value” is not the subjective process of valuing but rather what we aim to gain or keep, and she is certainly right that it is ideas that have made possible the tremendous growth in productivity since the Industrial Revolution, greatly aiding human survival. But I think there is danger of a misstep here. “Value,” in the sense of what we aim to gain or keep, must be distinguished from the economic value or price of something, which is determined by market actors’ subjective valuations. The Austrian theory of economic value is quite compatible with Rand’s account of “value,” though I’m not sure whether Objectivists do in fact accept it. But the misstep is to assume that in acquiring resources, people come to own the economic value of what they acquire and, as a corollary, to assume that people can acquire only things that the market values. Thus, if someone is the first to appropriate some rocks that no one else wants but that he, for reasons of his own, finds worth acquiring, he is just as much their owner as someone who sees the rocks’ economic potential and because of that is the first to use them.

For this reason, the fact mentioned by Mossoff, that oil was not a valuable resource “until humans invented steam engines and generators requiring lubricating oil and combustion engines requiring fuel” (p. 481) is no doubt true, but not on point, as this does not provide grounds for acquiring the physical resource of oil. If someone had been the first to use some deposit of oil, even though oil had no market value, why wouldn't have acquired it as his property?

Rand would disagree, as she holds that the

ultimate source of property … remains value-creating productivity … which is what is recognized and secured by IP rights … what makes something a value depends on the question to whom and for what. For instance, a desert is a disvalue to a farmer who instead requires fecund soil. Yet a desert may be of tremendous value to individuals inventing and producing integrated circuits, which requires silicon. The value is not the (scarce) object as such, but rather the value it represents to the rational mind, who is producing and using it in human life—the fundamental moral justification of all property. (p. 481)

All of this, to reiterate, seems to me to confuse why we want physical things and the basis on which we acquire them.

You might object that it’s unfair to deny inventors IP rights. Their ideas contribute more to the production process than anything else. Once an invention becomes known, why shouldn’t the inventor have the right to the economic gain people get from its use, at least for a period of time?

One answer to this is to appeal to and extend a point Rand herself makes in arguing for limited rather than perpetual patents. As Mossoff explains her view,

unlike with static material values, such as an automobile, dynamic claims to production of values do not require continued actions to sustain or keep them as values. Without having to maintain the value, such as taking one’s automobile to the mechanic to repair it, IP rights could over time become used by people doing nothing to sustain the value, but simply using the IP rights parasitically to leech from the value creation by others in creating new values (property) (p. 477)

Rand argues, in my view correctly, that holders of IP rights who do not contribute to the production process act parasitically: they say, “You must pay me for the use of the idea to which I hold a patent, even though the idea is public knowledge once disclosed.” Extending the argument, isn’t anyone who demands a fee for using his idea acting parasitically? If the inventor of an idea uses it in a production process, he gains the economic value of using it, and he secures extra gains if he’s the first user of the idea, but why do ideas entitle inventors to more than this?

Mossoff has with great skill compressed a large amount of material into his article, and I have been able to comment on only a few of his arguments. I do not think, though, that the other material requires revising my view that patents are unwarranted, though readers must judge for themselves. Patents lack a basis in natural rights; to the contrary, they may be, as Wendy McElroy has suggested, a patent absurdity.1

READ MORE:

https://mises.org/library/patents-and-progress

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.....................

inventing america…….

BY LARRY ROMANOFF •

Americans boast incessantly about their competitiveness and the miracles of their predatory capitalist system, but on examination these claims appear to be mostly thoughtless jingoism that transmutes historical accidents into religion. If we examine the record, US companies have seldom been notably competitive. There is more than abundant evidence that their efforts are mostly directed to ensure an asymmetric playing field that permitted them to avoid confronting real competition. And, in very large part, major US corporations have succeeded not because of any competitive advantage but by pressure and threats emanating from the State Department and military. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman stated the truth quite accurately when he wrote, “The hidden hand of the market will never work without the hidden fist. McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas.”

Xerox was once almost the only manufacturer of photocopiers in the world. Kodakwas once almost the world’s only maker of cameras and photo film; Where are Xerox and Kodak today? More recently, Motorola was the leading manufacturer of mobile phones; Where is Motorola today? US-based RCA Victor was one of the largest producers of TV sets in the world. Where can you buy an RCA TV set today? Where are the great Pan Am World Airways and Continental Airlines? Where are E.F. Hutton, General Foods, RCA, DEC, Compaq? Where are American Motors, Bethlehem Steel, Polaroid cameras, and so many more? Gone, because they couldn’t deal with effective competition.

Boeing Aircraft would be gone today if not for the extensive subsidies it receives from the US government. It’s true that Airbus receives subsidies too, but Boeing is supported by billions in US military research grants against which it can apply much of its current expenses. Not so many years ago, IBM was the only manufacturer of office and home computers. Where can you buy an IBM computer today? GE was once the largest manufacturer of electric home appliances, lights and lighting fixtures. Where is GE today? Transformed into a financial company, beaten out of all consumer markets because it couldn’t compete. IBM defenders will tell you that the company willingly abandoned the PC market to focus on mainframe computers and information services, but no company abandons a profitable market. The truth is that IBM faced manufacturers who could produce PCs for a quarter of the cost, and were forced out of the business. GE defenders would make a similar claim, but GE couldn’t compete in the vast consumer markets and was driven out too.

The three major US auto manufacturers are in the same position. Chrysler has been bankrupt three times already, and survives today only because of Fiat having taken it over. The great General Motors went bankrupt, and was saved only by $60 billion of cash injections from the US and Canadian governments – money which will never be recovered. And in spite of that, GM would have anyway disappeared from the earth if not for its sales in China – which are now three times GM’s sales in its own country; even Americans are refusing to purchase GM’s tired and dying brands. Only Ford has been able to keep its head above water, and then only just. We could produce a list of hundreds of US companies who thought they were great until they faced some real “competition”, and then rapidly disappeared. It’s true there are business failures in every country, but other countries don’t boast about their God-given omnipotence and their world-beating competitive supremacy.

Along similar lines, the Americans have never forgiven the Europeans and Russians for producing supersonic passenger aircraft after all US attempts failed. And they are unlikely to forgive China and Russia for the deployment of working hypersonic missiles when all domestic attempts have failed.

And then we have the genuine mythology of Alexander Graham Bell who didn’t invent the telephone, Thomas Edison who, by his own admission, never invented anything – including the light bulb, the Wright Brothers who were never the first to have powered flight, and the great Albert Einstein who plagiarized everything he published. The list is very long.

Descriptions of American ingenuity and competitiveness were never accurate or valid, but mere jingoism fabricated by Bernays’ adherents to further promote the self-serving mythology of virtuous American capitalism. The truth is that the large US companies thrived on only brute force, heavily supported by their own government to limit competition both domestically and abroad. The US government and military have always existed primarily to browbeat other nations and economies into submission, to help US corporations obtain unfair trade deals, exclusive access to resources and markets, effectively colonising and subjugating much of the world. American business has seldom been able to compete when placed on an equal footing with other competitors because the US business model works only on a “take it by force” basis. Kodak, Xerox, and so many other American icons disappeared when the playing field did indeed become level.

We need only look at the US domestic market to see the truth of this. When Japanese and German automobiles were finally permitted into the US market on equal terms, the American auto firms mostly entered a long slide to bankruptcy – because they couldn’t compete. Almost every computer and electronic device sold in the US today is a foreign brand because Americans couldn’t compete when the playing field was level. Motorola’s crappy phones were a great success until Nokia and others entered the US market. Harley-Davidson exists only because of a 50% import tax on competing motorcycles; Ford Motors would also be in bankruptcy if not for the heavy protectionist tax on light trucks. The American mobile phone companies and ISPs would disappear into the bankruptcy courts within a year if foreign firms were permitted into the market. Cisco Systems, the grand American Internet infrastructure champion, would within three months be reduced to assembling Playstations for Sony if Huawei were given free access to the US market. The story is the same for countless American firms that were once dominant in their home market but quickly disappeared when protectionist trade tariffs and duties were eliminated and foreign products could enter the US on fair or equal terms. The dominant US firms surviving today are able to do so due mostly to rampant protectionism and oligopolies created by the US government to ensure their survival.

The same is true in foreign markets. Few American companies have been able to survive in other countries, other than the fast-food chains. Most recently, Domino’s Pizza is leaving Italy with its tail between its legs after ten years of failure, blaming the bankruptcy on COVID. But there is a long string of American failures preceding this; E-Bay and Home Depot left China in tears a few years ago. Uber’s China business was taken over by Didi, and there are many more. Those American firms that have survived, have done so primarily by purchasing domestic brands and using that distribution system to support their foreign market entries, and most of those have succeeded only due to astonishing criminality in their foreign joint ventures.

And it is an axiom in the auto business that nowhere in the world can you buy an American car except in North America and China, and the China market may soon disappear in spite of what seemed an initial success.

At one time, US banks, radio and TV companies, print publishers and others were heavily restricted from mergers and takeovers on the sound basis that society needed to be protected from the predatory nature of concentrated ownership. But for the past 50 years the elites who control the large US corporations have exerted enormous influence on the government to remove domestic restrictions on monopolies, and eventually their political influence succeeded to the point where today the entire nation has only a few media firms, auto manufacturers, pharmaceutical firms, oil companies, telecommunications firms and major banks. In each case, companies were bought, merged, swallowed or bankrupted until only a few very large survivors remained.

American banking corporations were once permitted to operate only within a single state, in part to sensibly ensure that local deposits were converted to local development loans rather than being siphoned off to develop other richer regions. But the powerful East-Coast bankers, heavily supported by the FED, convinced the government that all those small regional banks needed “competition” to make them “more efficient” and to bring them into the big leagues of the modern financial world. And of course, once approval was received, most of the local banks were purchased, enticed into a merger, bankrupted or forced out of business, and now a small number of banks controls most of the US economy. And, as we would expect, the new mega-banks did indeed siphon off local deposits to richer centers, thereby vastly increasing the nation’s income disparity and relieving the government of its control of regional development. All the claims about the need for, and benefits of, competition were false. The purpose of these mergers and purchases was never to foster competition but to eliminate it. Today, a few major US banks control the bulk of the nation’s business, and instead of competing with each other in some meaningful way they generally conspire together to plunder their customers. Where there is real competition consumers have choices, but what are the choices with the banks? You can leave one bank that offers poor service while cheating you to go to another bank that will offer poor service while cheating you.

The US mobile phone system, an oligopoly, is the most expensive and dysfunctional in the world. An Internet-enabled smart phone that can be managed well in China for less than 100 yuan a month ($15.00) will cost $200 per month in the US. Until recently, SIM cards could not be removed, to prevent customers from changing suppliers; unlocking the phone to enable its use with another phone company or in another location, would lead to a $500,000 fine and a ten-year prison sentence, thereby protecting the oligopoly from competition. Like all American systems, communication was designed by and for the benefit of private enterprise, meant to hold consumers captive and milk them for every dollar they have. It was never considered as infrastructure nor designed with any thought of what was best for either the consumers or the nation.

This pattern prevailed in banking, transportation, telecommunications, the media, the petroleum industry and others, to create a situation where these giant firms could totally dominate an industry to control not only prices and production levels, but also the rates of both future investment and technological innovation in these industry sectors. Those innovations escaping this capitalist net were soon either driven out of business or were purchased and killed. These are precisely the same arguments American companies and the US government utilise today in China to pressure China’s government to open industry sectors to US multi-nationals, claiming the benefits of competition and the need for efficiency as necessary credentials to enter the modern world. These claims are equally as much a lie in China as they were in the US.

In fashion similar to their mythical inventiveness and entrepreneurship, nostalgic and misinformed Americans today pine for “the returning of pride once again to what was once the global standard of creativity, quality and style in manufactured products – the mark on all our goods saying ‘Made in the USA’”.

But this is just one more foolish American myth. The US was never a world standard of anything except weapons and maybe pornography, and even then they stole most of that from Germany and Japan. Mostly, American products, like their automobiles, have always been crappy. It is true there have been some products of acceptable quality emerging from the US, but these have always been much in the minority and the few examples used as evidence of this claim are virtually the only examples. The Americans have never been able to produce machines or tools that could match those of Germany, or shoes and clothing as fine as those of Italy, or wines and food products as good as those of Europe.

We are constantly reminded that the Americans, being so creative and innovative, spend huge amounts of money on R&D, but these claims are short on detail and therefore disguise the objectives of corporate R&D in America. Companies in most countries invest in research to produce products of higher quality and greater reliability or durability, but US firms typically have interest only in finding ways to produce more cheaply so as to enhance profitability. Large American firms focus at least 60% of their entire R&D budgets on ways to lower costs, with product quality inevitably being the loser. American investment in R&D is merely a kind of race to the bottom, with every firm competing to discover new ways to substitute substandard materials and produce a more cheaply-made product that can be sold at the same price. Many components are internal where the materials quality is not obvious to consumers, but for those which are external and subject to consumer evaluation we see superficial America at its best. Manufacturers conduct consumer tests of their R&D ‘innovations’ to determine if the public are able to detect the cheap substitutions, the goal being to degrade product quality and cost as much as possible in a way that will not be apparent to the consumer. Lawrence Mishel, President of the Economic Policy Institute, wrote that “the US is a country interested only in finding the shortest route to the cheapest product”.

Despite all the mythical propaganda, the Americans have never placed much value on a skilled work force, and the quality of American goods has reflected this for 200 years. Neither American people nor their corporations have ever valued product quality, the people having for generations been programmed to value superficiality and appearance over substance, eventually resulting in the almost universally low quality throwaway society we see today. One of the main results of this low-class attitude is the American use of technology. Companies in Germany, Japan, China, and much of Europe, will take advantage of new technologies to produce better and higher-quality products but the Americans almost invariably use it to lower their cost of production and raise their profits. Product quality is always the loser. Even today, a German Volkswagen that requires repairs after a year is an anomaly; an American Buick that doesn’t, is a miracle.

The American Entrepreneurial Spirit

Americans have a bad habit of sloppiness with their vocabulary, an unthinking and simple-minded tendency to contaminate definitions by exaggerating them beyond the bounds of all good sense, mostly to fabricate grist for the propaganda mill. One such foolishness is of course the American definition of democracy which sometimes seems to include a thousand unrelated and mostly mythical items like freedom. One American acquaintance stated that a pet’s ‘right to dog food’ was ‘a human right’ and therefore included within the meaning of democracy. I sincerely doubt that one American in 50 could provide an intelligent definition of either democracy or freedom; the words simply mean whatever each person wants them to mean, the media pundits even less intelligent than the rest of the population.

We have the same problem with the use of ‘entrepreneurial’ as an adjective, the definition often expanded to include things like innovation or creativity or independence, and sometimes even ‘freedom’, and of course including the filing of new patents. But when the US military funds MIT for weapons research and obtains useful discoveries, this is hardly an example of the entrepreneurial spirit at work. An entrepreneur is someone who takes the initiative to form a new enterprise, the term being only peripherally related to innovation or the generation of ideas. Richard Branson may be entrepreneurial in designing and building a new space ship for tourists, but for each one of these we have several million who open their own pet shop.

The Americans constantly flaunt companies like Microsoft, Google and Facebook as examples of their entrepreneurial abilities but, like most all else, the few examples claimed are virtually the only examples that exist. And in almost every case I know of, especially with examples like Google and Facebook, there was enormous government, State Department and CIA political involvement, heavy funding, and enormous commercial pressure without which these enterprises would never have seen the light of day. Google is virtually a department of the CIA; Facebook and Twitter may not be much better. Warren Buffett and Michael Dell may be exceptions, but there are precious few of these. Apple would qualify, as would the creation of Hewlett-Packard, but America’s list is much shorter than China’s, with firms like Huawei, Wahaha, Xiaomi and 50 million others who started their own businesses. Like all the supposedly great things about America, the nation’s entrepreneurial spirit is just another utopian myth created by the propaganda machine as one more aspect of brand marketing.

In the US, a new college graduate who has a job and isn’t already bankrupt with student loans, will take his first paycheque to a car dealership and borrow whatever he can to buy a car, and spend years paying off the debt. A new Chinese graduate will leave his full-time job at 5;00 PM and wash dishes in a Chinese restaurant until midnight, saving every penny until he can put a down payment on a house or an apartment which he will then rent out. And he will continue applying his salary from both jobs, supplemented by the rental income, until the house has enough equity for a down payment on a second property. And he continues, while he lives in a small rented flat, and after 5 or 6 years he has one house paid for, which he can then live in almost free, with another well on its way. He will continue to apply all income and rentals until the second home is also paid off, after which he can bank his entire salary and buy a new Mercedes if he wants one, or start his own restaurant, or buy a third house. Which way is better? Where is the evidence of “the entrepreneurial spirit” in the American?

Nevertheless, and in keeping with the American defense of their pitiful PISA scores and educational system, the propaganda machine never tires of boasting of the breadth and depth of entrepreneurial America, of the adventurous spirit that pervades the nation, of the US being a veritable hotbed of entrepreneurs and business leaders and inventors. But of all claims of American superiority, and in spite of all the blatantly false myths about every other part of American excellence, this claim is so silly as to defy understanding of its origin. In a lifetime of travel, I have almost never met an American who dreamed of having his own business, and the same is true for Canadians, Brits, Australians and Germans. Italians yes, many; Americans, none. But in more than 25 years of constant exposure to Chinese people, and in a decade of experience within China, I am still genuinely surprised to meet a Chinese who does not dream of having his or her own business. The desire to be one’s own boss is virtually embedded in Chinese DNA and would serve as one of the defining adjectives of the Chinese people. There is nothing in the US to compare to it, and there has never been. In fact, it is China, not the US, that is flooded with entrepreneurs and the spirit to strike out on one’s own. Ningbo, a small affluent city in East China, is known primarily for its abundance of millionaires, and has an extraordinarily strong private business base, with one in four local people involved in export-related industries. Where do we find this in America?

In the business school of the university in the small town of Yiwu, in Zhejiang Province near Shanghai, all the students – all the students – have their own businesses. They may only be Taobao online shops, but they all make money. In fact, it is part of their business-school curriculum that they at least open online shops to take advantage of Yiwu’s massive commodities markets, and learn how to buy, sell and market those goods across the nation. Many accept largish orders and market internationally – and these are kids. Some of them make $100,000 a year in this minor part-time occupation while they are still undergraduates. Many are also quite fluent in English and are taught to act as agents, purchasing advisors, negotiators and translators for foreign buyers, accumulating business skills and experience of enormous value. Where do you find this in America? Where do you find this at Harvard? The American business schools pretend that entrepreneurship entails imagining an iphone in your garage and finding an angel willing to pump $200 million into putting your show on the road. But for every one of those you can find in the US, China has 6 million of its kind, and guess who’s driving the Ferraris. And guess who spends 6 hours in front of the TV every night, still believing the sun revolves around the earth and still unable to find his country on a map of the world.

As well, if you read my E-book on ‘How the US Became Rich’,(1) it is heavily documented that great numbers of products which the mythological narrative now credits to American inventiveness were simply copied or stolen from other nations, often with the encouragement and financial support of the US government. Coca-Cola is one such example, but there are literally hundreds of others, including most manufacturing machinery and processes.

There are a great many of these “firsts” that were never American, but where the claim has been made and the title confiscated as part of the long series of historical myths used to bolster the jingoism of American supremacy. Americans firmly believe they are exceptional in their ability “to turn the abstract into practical products for everyday people to be able to afford”. In evidence, they produce a long list of products and consumer goods that evolved from their “scientific research”, and that, according to them, is “so long and obvious as to sound like bragging”. The only flaw in this mythical narrative is that none of the claims are true. Almost no items on their “bragging list” were invented by Americans, and in the cases where US residents were the first to apply for patents, they were not Americans but virtually all by immigrants who had built on someone else’s work. Many Americans believe that IBM created the personal computer, but Germany’s Konrad Zuse built the first functional programmable computer in 1936, and Olivetti in Italy as well as scientists in Russia and Poland had working computers long before that.

And it goes much further than this. The Americans are exceptionally proficient at creating historical myths that demonstrate their supposed moral superiority in virtually every area, freely rewriting history or carefully burying crucial facts in juvenile attempts to mislead. One such myth concerns the fabled military aircraft, the P-51 Mustang which, according to the Americans, single-handedly won the war in Europe, defeated the German Luftwaffe all by itself, and “is widely considered the best piston single fighter of all time”. Of course, it is no such thing, except to the Americans themselves. For one thing, the Americans’ brief flash at the end of the conflict hardly ‘won the war’ but, more importantly, this aircraft’s original designation was the XP-78, a name almost nobody has ever heard of, and for good reason. The aircraft’s performance was underwhelming to say the least and, with its American-built Allison engines was of no more use during wartime than a lawn mower. It was the re-fitting of this aircraft with the British Rolls-Royce Merlin engine that made it useful. With the Merlin generating twice the power with less than half the fuel consumption of the US engine, the aircraft did indeed have great range and performance – as did the Spitfires and other British aircraft, but the original American version wouldn’t have made a list of the top 500. And yet nowhere in any American narrative do important facts like these appear. In these areas, as in so many others, the US is a nation based on lies.

In related propaganda, anything developed first by another nation will not actually exist in the American mind or be recognised in the American narrative until it is subsequently copied and produced by the Americans, at which point they will assume full credit for having taken a flawed and primitive foreign concept and developed it into the only real good version. The British Harrier aircraft is one such example that comes immediately to mind, as are Italian espresso and cappuccino. On the other hand, any country creating anything similar to that existing in the US will discover its product being immediately denigrated as just a cheap copy of an infinitely-superior American invention. Americans are such a pain in the ass.

Creativity and Innovation

The floods of new patents notwithstanding, there is no evidence that Americans are any more innovative or creative than any other nation of people. Equally, there is no evidence that Americans are any more resourceful than people from other nations, and I would argue they are rather less so. Moreover, two major conditions serve as strong contra-indications of these claims of American inventiveness.

One is that most of the invention and innovation that occurred in the US was not done by “Americans”, whoever they are, but by people from other nations, a large percentage of these being Chinese. In fact, in America’s famous Silicon Valley 50% of the participants are Chinese and another 40% Indian. That wouldn’t seem to leave too much creativity or innovation for Americans. Indeed, without these foreigners, US innovation might come to a virtual standstill and Silicon Valley might have amounted to nothing. The US has for decades offered free graduate-level education and attractive research jobs to the best and brightest of other nations, which is simply colonialism in another form, effectively purchasing the brightest students from other nations then taking credit for their inventions or patents. The truth is that precious little of the inventiveness that occurred in America in the past was ever done by Americans. Even today, a recent study financed by New York mayor Bloomberg proved that 75% or more of all patents emerging from US educational institutions were obtained by foreigners, a great many of whom were Chinese. The US educational system has never fostered either inventiveness or creative thinking; what it has done, and perhaps done well, is to hire creative minds from other nations and then claim their work for itself. It has been only through plundering resources and the brightest people from other nations, that the US has progressed and become rich overall. If not for that, America today would be of no more consequence than Australia.

The second is that a surprising amount of the innovation emerging from America in recent decades did not come from lofty ideals, satisfying consumer needs, or other moral truisms, but was simply commercial fallout from military research. As noted elsewhere, MIT, one of the most prominent and praised US educational institutions, was created for the sole purpose of military research and until recently was almost 100% funded by the US military. The US may well have its share of intelligent and innovative people, but their talents have been mostly directed to war, marketing, and the marketing of war. When the Americans were flooding the people of Vietnam under a tsunami of millions of liters of napalm, they discovered the Vietnamese were cleverly avoiding their planned immolation by submerging themselves in water and extinguishing the flames. The Department of Defense quickly assembled the best and brightest Americans (at Harvard) who, innovative as always, discovered they could infuse the napalm with particles of white phosphorus that would burn a man to death even while under water. American ingenuity at its best.

The US government has arranged widespread ‘public-private partnerships’ with many educational institutions for the purpose of military research, and after the military determines how to weaponise something, they then let parts into the private sector. The Internet was a military project, as was the American GPS system. Google Earth resulted from US military spy satellites; radio, computers and microwaves were military projects. The list is long. When this massive seconding of the American educational system for military use became a target of public objection, the US government did what it and its corporations always do: they moved it offshore. In late 2013 der Spiegel reported an outbreak of public condemnation when it was revealed that German universities had received tens of millions of dollars from the US for military research, and many other foreign universities are in the same position. The Americans are now attempting to utilise the best and brightest from all Western nations in their headlong rush to create military invincibility, hijacking the research departments in the world’s universities and paying scientists and researchers from all nations to make their contribution to American military superiority.

Americans are not “inventive”. They are greedy and self-serving, interested much more in commercial domination and control than in creativity. Creativity is defined by art, not by money and, since Americans have no art, they have redefined creativity as something that produces money. And it’s even worse than this. As I’ve noted elsewhere, about two-thirds of American R&D budgets are directed exclusively to finding ways to degrade product quality and lower the cost so as to make a cheaper product and increase profits. In what way is this a reflection of “creativity”? Even worse, the US government and corporations have not only hijacked all American universities as incubators of profit but also as hotbeds of weapons research, now extending this to the research departments of universities in other Western nations. I’m sorry to say this, but of all the available fields of human endeavor that would benefit from the application of imagination, the Americans have chosen only two: the search for ways to provide less while charging more, and ways to kill more people faster and from a greater distance. This is not creativity. It is a kind of mass hysteria in a population that long ago lost its moral compass and sense of values, a people rendered powerless by a profusion of propaganda that redefined a life worth living as one of superficiality, greed and domination.

In late 2015, Robert McMillan wrote an article in the WSJ in which he noted that China’s supercomputing technology is growing rapidly and that China has had for years the world’s most powerful supercomputers. China’s Tianhe-2, which had for years been ranked the world’s most powerful supercomputer, could perform 34 quadrillion calculations per second. The machine in second place, the US military’s installation at its Oak Ridge National Laboratory, could perform 17 quadrillion calculations per second – exactly one-half as fast as China’s, and this in spite of spending billions of dollars to improve their capability. McMillan stated that the increasingly poor American results are not from a slowdown in the US effort but an acceleration of research in China. Only a few months later, Xinhua news reported that China’s National Supercomputer Center would soon be releasing the prototype of a supercomputer that will be 1,000 times more powerful than its original ground-breaking Tianhe-1A (which was then superseded by the Tianhe-2). A few months later, in 2016, China introduced its new supercomputing system, Sunway-TaihuLight, the world’s fastest for the seventh straight year, and using entirely Chinese-designed processors instead of US technology. This new Chinese computer is capable of 125 petaflops, or quadrillion calculations per second, more than seven times faster than America’s Oak Ridge installation, and the first computer in the world to achieve speeds beyond 100 PFlops. The supercomputer’s power is provided by a domestically developed multi-core CPU chip, which is only 25 square centimeters in size. As well, in 2015 China displaced the US as the country with the most supercomputers in the top 500, China having 167 and the US 165, with Japan third at only 29.

I must say it was not only comical but instructive to follow the heavily-politicised transcript emerging from the US government on these ‘computer wars’, and so heavily parroted in the US media. For years, the Americans published – at full volume – lists of the world’s fastest computers, with their equipment always leading the pack, with calculation speed being the only appropriate measure. In that process, US government officials and the American mass media took advantage of every opportunity to denigrate the Chinese for their lack of innovation. Then one day Chinese engineers produced a supercomputer twice as fast as the Americans’ best effort, and suddenly the goalposts were moved. The measure was no longer calculation speed but the fact of using home-grown processors, so even though the Chinese machines were much faster than those of the Americans, they were using US-sourced microprocessors, so the Americans still won. The US government and media even enhanced their deprecation of China, loudly proclaiming that China would be nothing without US technology. So Chinese engineers designed their own microprocessors and produced a supercomputer five times faster than the best the Americans could manage, and suddenly the Americans have disappeared from the radar. Neither the US government nor the media appear to have any further interest in either the capability or the numbers of supercomputers, and the Americans seem to have lost interest in publishing lists of the world’s fastest computers. But on the bright side, Chinese authorities report that the NSA has launched hundreds of thousands of hacking attacks, looking for a way to steal and copy the technology for China’s new microprocessors.

Mr. Romanoff’s writing has been translated into 32 languages and his articles posted on more than 150 foreign-language news and politics websites in more than 30 countries, as well as more than 100 English language platforms. Larry Romanoff is a retired management consultant and businessman. He has held senior executive positions in international consulting firms, and owned an international import-export business. He has been a visiting professor at Shanghai’s Fudan University, presenting case studies in international affairs to senior EMBA classes. Mr. Romanoff lives in Shanghai and is currently writing a series of ten books generally related to China and the West. He is one of the contributing authors to Cynthia McKinney’s new anthology ‘When China Sneezes’. (Chapt. 2 — Dealing with Demons).

READ MORE:

https://www.unz.com/lromanoff/creativity-entrepreneurship-and-other-american-myths/

READ FROM TOP.

ONE OF THE MAIN INVENTION OF THE USA not mentioned here IS THE AMERICAN DOLLAR. IT IS DESIGNED TO CONTROL EVERYONE AND EVERYTHING....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..... IMPRISONMENT AND TORTURE ARE BOOMING INDUSTRIES IN THE USA.... EVEN IF PRACTICED IN OTHER COUNTRIES ON BEHALF OF THE YANKEES....