Search

Recent comments

- patriotism....

9 hours 29 min ago - belittling russia......

9 hours 57 min ago - Запад толкает Украину на последнюю битву....

10 hours 11 min ago - fourteen points....

10 hours 20 min ago - der philosophische glaube....

10 hours 31 min ago - seriously?...

10 hours 45 min ago - AfD....

11 hours 12 min ago - undesirables...

11 hours 29 min ago - assistant spies......

11 hours 54 min ago - brics.....

15 hours 2 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the threat to our 'sustainable population' .....

from Crikey .....

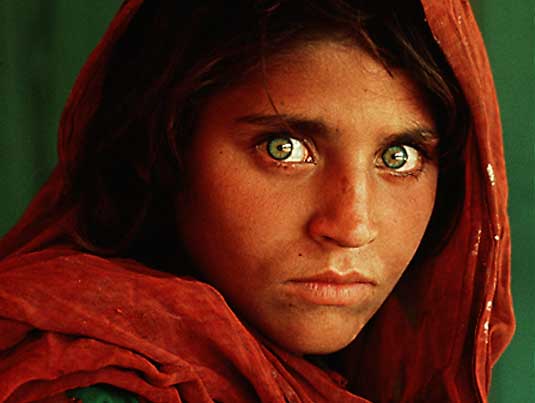

meet a 'queue jumper'

by Y Dr Tanya Ahmed, a psychiatry registrar

Her brown eyes are blank. Her face is expressionless, her body motionless. She has no thoughts, no feelings, no purpose. She huddles in the corner of a stark hospital ward. She does not respond when her children kiss her. She hasn't drunk today, and hasn't eaten for days. If only she had the energy, she would find a way to die.

She has just arrived in this foreign land. She doesn't understand what people around her are saying. Nothing is familiar. It's not home. Attempts to sooth and comfort are misunderstood. She flinches from my touch. She doesn't trust me, or anyone. What little she says shows she feels she is being punished. She feels guilty. And she is guilty - guilty of leaving a country in turmoil.

She tried to do what Australians would call the right thing. Desperate to preserve what's left of her family, to keep her young children safe, she wanted to raise them in a place without fear, persecution and the smell of death. She tried to get a passport but couldn't - her country's government won't give passports to women still able to bear children, still young enough to fight in the army. Even if their husband has been killed in battle. Without a passport, she couldn't get a visa. Of course you could argue that in leaving, she was avoiding the legal requirements of her country. That's true. So were the people who died trying to scale the Berlin Wall.

She grew despondent. There was no queue she could join. She chose to leave despite the risks - her country has a shoot-to-kill policy on its borders, but staying seemed a bigger risk. She paid some people to get her across the border. A long walk, sleeping rough, hiding from authorities, fearing her children would be killed, finally paying for a place on a boat.

The grief, the loss, the fear, the dislocation, the death took its toll. Now she sits empty, blank, broken.

She is a boat person. She is the reason we're beefing up border security and why we're set on off-shore processing. She is the threat to our sustainable population.

She, and hundreds like her, come to Australia hoping for freedom and a chance to live without fear. But she won't find it here. If she lives, she'll be confronted by harsh detention facilities, years of uncertainty, entrenched systematic discrimination and marginalisation. Even the social welfare system will be powerless to help.

We, the citizens of this country, have allowed political fear-mongering to blur our vision and humanity. We, aside from those remarkable few who campaign tirelessly to support her and those like her, are part of the problem, not the solution. "Stop the boats" is the political catch cry, and it seems we voters like it.

The reality is that these boats provide a service - like it or not, they are the only way out for her and people like her. They provide an escape from intolerable brutal and deadly conditions. Consider the paradox - our troops serve in places boat people come from. Yet we suggest people leave these places lightly, for "economic reasons", as if they would cross dangerous seas for a better paid job. To think we can stop people from leaving danger is naive. To think we should turn them around is inhumane.

The violent slide between asylum seeker and the international terrorist has worked - asylum seekers are now sources of our collective fear. Neither Julia Gillard nor Tony Abbott wish to clear up this awful and deliberate lie.

This woman has risked her life to find a better life for her children. She is a queue jumper. All 30 kilos of her.

And she is a chilling reminder of what is at stake in the global economies of fear.

Dr Tanya Ahmed is a registrar in psychiatry and principal of the health and communications consultancy RaggAhmed.

- By John Richardson at 7 Aug 2010 - 11:18am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

in true aussie tradition .....

Australia since 1788 has been made of and by immigrants. It still has an intake program of over 150,000 new settlers each year, yet the arrival of boats carrying a few hundred asylum seekers invariably causes a frenzy.

Australia is not unique in viewing with alarm the phenomenon of irregular migration, but its responses are (and apparently always have been) completely out of proportion to the threats posed.

In immigration history, fear is an almost constant feature. The indigenous inhabitants had everything to fear from the first white settlers. For the convicts and jailers on board those ships, the ancient land, its animals and peoples were forbiddingly strange. The settlers' sense of cultural isolation grew as the colonies expanded, fostering a defensiveness that made immigration control a legislative priority.

The constitution does not provide directly for citizenship, but confers on parliament the power to make laws regarding naturalisation, aliens and immigration. That ensures politics looms large in determining who is considered ''Australian''.

The fears underlying White Australia Policy were given visceral expression during and after World War II. Newsreel images included graphics tracing the menace of invasion from populous Asian countries. The very real threats from the Imperial Japanese Army gave way to more inchoate fears about Vietnam first and then Indonesia.

The eventual challenge was constituted not by an invading army, but by asylum seekers coming in search of protection. Australia's response has revealed the extent to which fear has shaped our national character.

About 23,000 people have come by boat without authorisation since 1978, averaging a little more than one ''boat'' person every two days since the end of the Vietnam War. In spite of the modesty of these numbers, the phenomenon has engendered extraordinary responses from government.

Public support for immigration programs generally has always been tenuous. Electoral support has remained strong for the harshest measures taken by the Coalition government in and after 2001 - the interdiction and ''push back'' of unauthorised boat arrivals, and the processing of refugee claims offshore. This is so even though distaste has grown for the excesses of that period during which children and vulnerable individuals were detained for long periods in remote and punitive conditions.

The cost of the policies is easy to articulate. In financial terms, constructing detention facilities in remote locations has been exorbitant. Over $1 billion was spent housing and processing barely 1500 asylum seekers on Nauru and Manus Island between 2001 and 2004; more than $400 million was spent constructing the high-security facility on Christmas Island commissioned by the Labor government in 2008. Even at the height of the global financial crisis, money was no object.

The sometimes appalling conditions in the detention centres have inflicted terrible injuries - both physical and psycho-social - on all those involved. Hundreds of people have died at sea trying to seek asylum in Australia. Between December 1998 and December 2001, it is estimated that 891 boat people lost their lives. These deaths cannot be blamed solely on uncaring people smugglers. At least some of the deaths were related directly to push-back operations.

Conservative politicians have become adept at exploiting the popular (almost acculturated) fear of outsiders as an electoral weapon. Such strategies may come at great cost to the cohesiveness of a multicultural, multiracial society like Australia's. Electorally, however, they are very effective.

Once out of the bottle, the fear genie seemed to take hold of progressive politics. Kevin Rudd tried to find a balance between compassion and control, but the message was confused. It translated into disastrous opinion polls. Julia Gillard then told those alarmed by ''boat people'' that they did not deserve to be demonised as ''rednecks''.

It is clear no one sees the asylum seekers as a direct threat to Australia. If this were the case, the opposition would be working with the government (as Labor did in 2001). Instead, it has sought to score political points by announcing loudly to the world that Australia is now a ''soft touch'' country with weak border controls. One might well suggest the opposition's loose lips have helped to bring the ships which are causing such anxiety. People smugglers seeking clients in troubled countries could not hope for more effective advertising of their product. Having tried a softer and more humane approach, Labor is now running scared of an electorate energised by opposition rhetoric.

In an age of instant communications, nuanced explanations of international law and human rights are difficult to deliver. Conversely, it is easy to characterise unauthorised arrivals as illegal invaders: at worst as fearful harbingers of all things dreadful; at best as queue jumpers. The asylum seekers' vulnerabilities are lost. The compassionate response is denigrated as folly.

Although intended as a circuit-breaker, Gillard's speech to the Lowy Institute last month takes the country back to the dark days of the Tampa affair. It perpetuates a cycle of irrational policymaking and profligate spending, all likely to end in continuing human rights abuse, injury and more deaths, and continuing damage to Australia's international standing.

Pushing back the boats is no answer because there is no country in the region that would take them. Neither will establishing processing centres in Third World countries stop the boats. Historically, this has only ever been achieved by agreements with the countries at the source of the asylum flows. With Vietnam, it was the Orderly Departure Program. In the mid-1990s a memorandum of understanding with China stopped the flow of boats from there.

The number of refugees who come to Australia as asylum seekers - by plane or boat - is minute in world terms. The numbers are manageable. Most come because of prior connections with communities in Australia. It should be possible to work with those communities to put the people smugglers out of business. Instead, we threaten these same communities with heavy criminal penalties if they so much as admit to helping those who use irregular means to seek Australia's protection from persecution.

Mary Crock is professor of public law at the University of Sydney. This is an extract from her essay in the latest edition of the journal Dialogue.

Scapegoating Boat People