Search

Recent comments

- waste of cash....

2 hours 24 min ago - marles' bluster....

2 hours 45 min ago - fascism français....

2 hours 49 min ago - russian subs in swedish waters....

3 hours 28 min ago - more polling....

2 hours 57 min ago - they know....

7 hours 45 min ago - past readings....

8 hours 44 min ago - jihadist bob.....

8 hours 51 min ago - macronicon.....

10 hours 45 min ago - fascist liberals....

10 hours 46 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

an offer of peace...

taliban

taliban

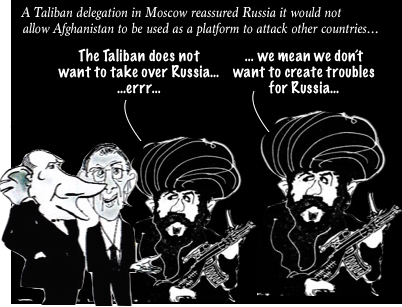

MOSCOW, July 9 (Reuters) - A Taliban delegation in Moscow said on Friday that the group controlled over 85% of territory in Afghanistan and reassured Russia it would not allow the country to be used as a platform to attack others.

Foreign forces, including the United States, are withdrawing after almost 20 years of fighting, a move that has emboldened Taliban insurgents to try to gain fresh territory in Afghanistan.

That has prompted hundreds of Afghan security personnel and refugees to flee across the border into neighbouring Tajikistan and raised fears in Moscow and other capitals that Islamist extremists could infiltrate Central Asia, a region Russia views as its backyard.

At a news conference in Moscow on Friday, three Taliban officials sought to signal that they did not pose a threat to the wider region however.

Read more:

GusNote: Gus understands that 85 % of the territory is about 15 % of the population...

Free Julian Assange Now !!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 10 Jul 2021 - 8:44pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

recalibrating...

by Kit Knightly

The “big news” in the last couple of days is the American “drawdown” in Afghanistan. Yes, after nearly two decades, the US is finally pulling its troops out of one of the many countries they never had a legal right to be in.

“President” Biden re-affirmed today that the US will be pulling all its forces out of the country by August 31st, adding that the people of Afghanistan must “decide their own future”.

This is being sold all across the media as an end to the (totally illegal and obviously economically motivated) war. Not only that, but the universal message is that ending the war is a bad thing.

The Economist headlines “America’s longest war is ending in crushing defeat”, and warns that life for the Afghanistan people will be worse once NATO has left.

Politico mournfully atones that America “never understood” its war there. While the New York Times comes over all nostalgic and compares the US leaving Afghanistan to the “betrayal” at the end of the Vietnam war in 1975.

Further coverage is already trying to sell us the “cost” of the US withdrawal.

The BBC is reporting that the Taliban are making territorial gains, and the Guardian report that Iran and Russia will step into the “diplomatic vacuum” in the region.

The Evening Standard is going one better, and already priming people for the idea NATO forces will have to go back and start again: “We’ve left Afghanistan but we may well be back“.

But is all this messaging accurate? Is the fighting really over? Did Biden just end a war?

No. Absolutely not. And the official channels are being more than clear about that.

The US acting Air Force Secretary John Roth has already said they have the “Over the Horizon” plan, a 10 billion dollar scheme to fly drone strikes over Afghanistan from airbases in Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE.

On Tuesday, in a press briefing, Pentagon press secretary John Kirby was asked how the US might assist Afghan National Security Defense Forces in the future, he responded:

the way you’ve seen it being conducted in the past – through airstrikes.

Airstrikes and drone strikes will carry on, the White House and Pentagon have been completely up-front on that (The Institute for Public Accuracy has done great work collating all the quotes.)

So, the “war is over”, but the United States will continue to drop bombs on Afghanistan as and when it feels like it (each and every one of those bombs is an individual war crime, by the way).

It is not going to be limited to bombs either, more evidence of how the war in Afghanistan will continue is available right here in the pages of USA Today, which ran a story headlined: “Here’s how we can save Afghanistan from ruin even as we withdraw American troops”, and suggests:

new ways to sustain several thousand Western contractors in or near Afghanistan are needed

“New ways to sustain contractors”, loosely translated, means “more money and weapons for mercenaries”.

For those who don’t know, “contractors” is almost always media speak for “mercenaries”. And “contractors” in Afghanistan have been in the news a fair amount the last few months.

In May, when the “drawdown” was allegedly beginning, NY Magazine reported:

The US Is Leaving Afghanistan? Tell That to the Contractors. American firms capitalize on the withdrawal, moving in with hundreds of new jobs.

Going on to point out [emphasis added]:

Contractors are a force both the US and Afghan governments have become reliant on, and contracts in the country are big business for the U.S. Since 2002, the Pentagon has spent $107.9 billion on contracted services in Afghanistan, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis. The Department of Defense currently employs more than 16,000 contractors in Afghanistan, of whom 6,147 are U.S. citizens — more than double the remaining US troops.

So, even before the “drawdown”, there were more mercenaries in Afghanistan than actual troops. And they’re not leaving.

Even back in December, it was already rumoured that Blackwater “could replace US soldiers in Afghanistan”.

In short, there WILL be US and NATO ground forces in Afghanistan. They’ll just be there as “civilian contractors” or “military advisors”. Western troops will go over in a “private capacity” working for Blackwater or some other mercenary company which also happens to get contracts from the State Department or the CIA.

Meanwhile, the US forces supposedly “abandoned” a key base in Bagram just a few days ago, leaving behind weapons, “hundreds of armoured vehicles”, and over 5000 “Taliban prisoners”.

We’ve seen this before, haven’t we?

Anybody covering the conflict in Syria is more than familiar with US “private security forces” and “Western-backed militias” and all the other coded language MSM outlets use when they don’t want to say “mercenaries”.

Anyone who followed the conflicts in Ukraine and Yemen, or the sudden growth of ISIS, has seen the roundabout ways American equipment will “accidentally” find its way into the hands of “terrorists”, “insurgents” and “opposition forces”.

This is not new. This is just the way the US fights its wars now.

Honestly, to even consider that the United States would totally withdraw from Afghanistan is to live in a fantasy world.

As I wrote back in December of 2019, Afghanistan is a massive success for the Deep State, and the business opportunities alone are way too profitable to ever let go.

Firstly, the CIA didn’t spend twenty years re-building Afghan opium farming just to give it up now. Recent estimates say that Afghanistan produces 90% of global heroin, a HUGE source of dark money for the Deep State.

Secondly, Afghanistan is home to gigantic reserves of metals and minerals. In fact as much as 1 TRILLION dollars of rare-earth elements, especially lithium which is vital to producing (among other things) the batteries used in every single mobile phone, laptop and tablet on Earth.

Let’s be clear, the US as an Imperial power simply cannot afford to give up Afghanistan. And they won’t. They’ll just recalibrate their word use and carry on. They’ll use the “drawdown” to earn some good-boy points with the anti-war crowd, whilst funnelling Pentagon funds into paying mercenaries and training proxies.

They will claim to be “ending the war” and, as is the modern way, simply carry it on under a different name.

“Private security firms” will carry out “targeted anti-terrorist operations”, or “precision strikes” will take out “known international criminals”…but no one will use the word “war”.

The US troops might be leaving the borders of Afghanistan, but the Imperial influence will remain, the corporate exploitation will continue, the fire will still fall from the sky, and there will be no peace.

Read more:

https://off-guardian.org/2021/07/09/no-joe-biden-is-not-ending-the-war-in-afghanistan/

See also:

automatic killer robots...iran vs taliban?...

As Western forces exit Afghanistan, Iran is watching with alarm. The resolution of one longstanding aim, the withdrawal of U.S. troops, is unleashing a separate challenge: what to do about the Taliban, another longtime problem for Iran, swiftly regaining power and territory next door.

The Afghan government said Friday that the Taliban had captured a key border crossing between Iran and Afghanistan.

Iran, ruled by Shiite clerics, and the Taliban, a radical Sunni movement, are at fundamental odds, and Iran has long bristled at the Taliban’s treatment of non-Sunni minorities.

Tehran fears both Taliban rule and Afghanistan returning to civil war, a destabilizing prospect likely to imperil the country’s ethnic Persian and Shiite communities, send more waves of Afghan refugees across the border and empower Sunni militancy in the region.

Seeking an upper hand, Iran has cultivated ties with some Taliban factions and softened its tone toward the extremist group, which it sees as all but certain to remain in power.

That gamble has elicited fierce debate in Iran, where the repressive Taliban is viewed unfavorably and skepticism of U.S. intentions runs high, even as the Biden administration makes slow headway in talks to return to the 2015 nuclear deal, from which then-President Donald Trump withdrew.

“Iran is going to be harmed immensely by chaos and civil war in Afghanistan,” said Fatemeh Aman, a nonresident senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, citing in particular Tehran’s fear of the Islamic State’s Afghanistan affiliate gaining ground. “They see partial rule, as the best-case scenario, with the Taliban in power.”

But Iran’s increasingly public overtures to the Taliban “could be a miscalculation,” said Aman, as “Iran believes they are using the Taliban, but some could argue that the Taliban is using Iran to present themselves as more powerful, worthy of ruling a country.”

Iran was excluded from U.S.-Taliban talks in Doha, Qatar, which last year led to a troop withdrawal deal to end two decades of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan. Biden set a Sept. 11 deadline, but the U.S. military said this week that the exit was more than 90 percent complete.

The Taliban, thought to control around a third of Afghanistan, has so far largely gained ground without full-scale fighting and has instead relied on cutting deals with local leaders.

Still, more than 1,500 Afghan soldiers fled across the border to neighboring Tajikistan in recent weeks to escape Taliban advances, while some 200,000 Afghans have fled their homes this year.

The Taliban’s fast-paced advances have left Tehran fearing the possibility that the Taliban could retake Kabul — but even more so the specter of widespread violence emboldening the flow of extremists, narcotics and weapons, said Aman.

In recent weeks, some Iranian hard-liners — aligned with Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and President-elect Ebrahim Raisi — have gone on the offensive and publicly painted a rose-tinted picture of a changed Taliban.

In late June, the ultraconservative Kayhan newspaper, tied to the supreme leader, declared, “The Taliban today is different from the Taliban that beheaded people.”

Kayhan argued that the Taliban’s recent gains have not involved “horrible crimes similar to those of the Islamic State in Iraq,” and noted that the Taliban has even said it has no issues with Shiites.

Similar statements followed. Hessam Razavi, the foreign news editor at the hard-line Tasnim News Agency, which is close to the Revolutionary Guard Corps, told an Iranian TV program last month that there has been “no war between Shiites and the Taliban in Afghanistan.”

Some hard-liners rejected this conciliatory take. Last week, the front page of conservative newspaper Jomhouri Eslami criticized Iranian leaders for playing down the threat of “Taliban terrorists” along Iran’s border.

On Persian-language social media in Iran and Afghanistan, others condemned Iran’s leaders over perceived efforts to whitewash the Taliban’s bloody history of attacking Hazaras, a Shiite minority, and repressing women and personal freedoms.

In one incident seared in Iranian memory, Taliban insurgents in 1998 attacked the Iranian Consulate in Mazar-e Sharif in northern Afghanistan and killed nine Iranians. The two sides nearly went to war.

The outgoing government of centrist Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, meanwhile, has been more circumspect regarding the whiplash developments across the border.

“We are seriously considering the issue of Afghanistan and talking to all Afghan groups,” Saeed Khatibzadeh, a spokesman for the Foreign Ministry, said late last month, the Aftab Yazd newspaper reported. “A genuine dialogue between Afghans is the only lasting solution,” he said. “We are ready to facilitate talks. “

While “the Iranians do care about Afghanistan . . . there is no clear strategy for how they are going to handle it,” said Vali Nasr of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Some in Iran celebrated the withdrawal as “a U.S. failure,” said Nasr. But others have argued that the “United States welcomes Afghanistan becoming a quagmire for Iran,” and that withdrawal “is priming Afghanistan for sectarian rule,” he said.

Even before the Doha deal, Iran cultivated ties with Tehran-friendly Taliban factions, as Afghanistan’s other neighbors, especially Pakistan, have done for decades.

Forging such ties was encouraged by the rise of the Islamic State’s Khorasan offshoot in Afghanistan in 2015. Iran began to see it as a bigger threat than the Taliban, which also opposes the ultraviolent group.

Iran’s long-simmering Taliban ties have become increasingly public. In 2016, a U.S. drone strike killed Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour as he returned to Pakistan after a stay in Iran. In the most high-level meeting between the parties, senior Iranian officials hosted a Taliban delegation in Tehran in late January.

The new head of Iran’s Quds Force in the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Ismail Qaani, also has extensive ties and experience in Afghanistan.

Iran and the United States, however, have in the past found common ground around fighting the Taliban.

As the United States prepared to invade Afghanistan in 2001, Iran, then led by reformist President Mohammad Khatami, provided intelligence. Then-Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani reportedly oversaw the contact.

After the Taliban fell, Iran continued to help build a new Afghan government and mediate among warlords filling the security void.

But that cooperation ended in January 2002, when President George W. Bush named Iran, North Korea and Iraq an “axis of evil,” offending Tehran.

Now, Aman said, Washington and Tehran have a small window of time to cooperate again in Afghanistan’s interest.

“I hope they don’t wait for a civil war to sit down and talk as much as they can over Afghanistan,” said Aman. “Afghanistan has suffered so much from the differences and animosity between Iran and the U.S., and Iran and Saudi [Arabia] and Arab neighbors.”

Read more:

https://www.stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/2021-07-10/iran-us-withdrawal-afghanistan-2109591.html

Read from top

ready to go back?...

The federal government is prepared to send Australian soldiers back to Afghanistan if needed to prevent terrorist threats, Defence Minister Peter Dutton has declared after confirming the withdrawal of troops in recent weeks.

Mr Dutton raised the possibility of deploying special forces if and when a new mission served Australia’s national interest or the interests of allies such as the United States.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/australian-soldiers-could-go-back-to-afghanistan-if-needed-dutton-20210711-p588p0.html

haven't got enough bruises yet?

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !

ruskies to the rescue...

Despite years of policy and rhetoric designed to reproach Moscow, Washington now needs help containing the Taliban.

Written by

Ted Galen Carpenter

Recent media reports indicate that the United States is seeking Russia’s acquiescence for the use of military bases in Central Asia to help contain the Taliban’s power following the completion of the U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan. The Kremlin’s response so far has been unclear. Initially, Vladimir Putin’s government seemed inclined to oppose a new U.S. military presence in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, countries that are under heavy Russian influence. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov supposedly conveyed a message to Washington during Vladimir Putin’s summit with President Biden, warning the United States against deploying its troops in the former Soviet Central Asian nations.

However, Moscow’s attitude may be shifting. A July 17 Reuters article reported that Putin had even offered to let the United States utilize Russian bases in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, albeit for limited, intelligence-gathering purposes. A story in the Russian publication Kommersant, citing confidential sources, largely confirmed that such an offer was in play.

Two aspects of this episode are notable. One is that the Biden administration has the gall to seek the Kremlin’s acceptance of a U.S. military presence in Central Asia, despite the openly hostile stance toward Russia that American officials have pursued. The other remarkable feature is that Putin has not summarily rejected such an initiative.

U.S. and NATO provocations toward Russia have not eased since Biden took office. Indeed, they seem to be intensifying. In just the past few weeks, several new incidents have occurred. On July 16, Washington signed an agreement with Hungary specifically giving U.S. forces the right to utilize two air bases. On July 12, the United States and 11 NATO allies launched a series of war games in the Black Sea. That set came on the heels of the 32-nation, 2-week-long war games in the same body of water. Such military maneuvers are inherently menacing to Russia, since they take place in close proximity to its crucial naval base at Sevastopol. Farther north, U.S. forces conducted joint “military drills” with units from Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania.

War games are not the only manifestation of U.S./NATO hostility toward Russia. In mid-April, the Biden administration expelled Russian diplomats and imposed new sanctions on Moscow for its alleged interference in the 2020 U.S. elections and its supposed failure to take action against cyberattacks emanating from Russian soil. The administration even pressured German Chancellor Angela Merkel for an agreement to orchestrate a united response among the European allies if there were indications that Moscow seeks to use the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline for leverage on other issues.

Biden himself did little to ease the already frosty bilateral relationship with the Kremlin when he described Putin as a killer with no soul. The subsequent summit between the two leaders was conducted in an orderly, professional manner, but there was no indication of a rapprochement between the two countries.

Washington sought to enlist its NATO partners to embrace a confrontational policy toward Moscow, and the communique following the alliance summit in June confirmed that the effort had been successful. The language in that document made it clear that the United States and its allies regard Russia as a dangerous, authoritarian adversary determined to undermine the security and liberty of the Western democracies.

An early passage stated bluntly “Russia’s aggressive actions constitute a threat to Euro-Atlantic security.” One later passage made the complaint more explicit: “Until Russia demonstrates compliance with international law and its international obligations and responsibilities, there can be no return to ‘business as usual.’ We will continue to respond to the deteriorating security environment by enhancing our deterrence and defence posture, including by a forward presence in the eastern part of the Alliance.” The delegates, however, insisted that “NATO does not seek confrontation and poses no threat to Russia” — an assurance belied by multiple alliance actions since the mid-1990s.

A lengthy and indiscriminate litany of grievances followed. “In addition to its military activities, Russia has also intensified its hybrid actions against NATO Allies and partners, including through proxies. This includes attempted interference in Allied elections and democratic processes; political and economic pressure and intimidation; widespread disinformation campaigns; malicious cyber activities; and turning a blind eye to cyber criminals operating from its territory, including those who target and disrupt critical infrastructure in NATO countries.” Ukraine was high on the list of the Alliance’s roster of complaints and demands, as was virtually every aspect of Russian policy toward Georgia, Moldova, and other neighboring states.

To be sure, Russia is not innocent regarding the deterioration of relations with the West. Moscow’s conduct toward its smaller neighbors in Eastern Europe sometimes has been overbearing and abrasive. The Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea and support for separatists in eastern Ukraine — even though those moves were a reaction to previous U.S. and European Union meddling in Ukraine’s domestic politics — violated international law and exacerbated an already volatile situation. The buildup of missiles and other military hardware in its Kaliningrad enclave also has increased tensions. Nevertheless, the bulk of provocations and destabilizing actions have come from the United States and its allies.

U.S. policy toward Russia before and after the NATO summit epitomizes what I have described elsewhere as Washington’s fondness for “capitulation diplomacy.” The essence of that approach is to adopt belligerent rhetoric, provocative military moves, and a laundry list of demands while offering few, if any, meaningful concessions to the other party. However, the Biden administration now finds itself in the awkward position of needing Moscow’s cooperation to advance U.S. strategic objectives in Central Asia.

One could readily understand if Putin responded to U.S. overtures by telling Biden to go pound sand. If he does not do so, it suggests that either Washington is prepared (however quietly) to offer some concessions on issues important to Russia, or that the Kremlin fears the threat of radical Islam and China’s growing clout in Central Asia even more than it does a U.S. military presence. One thing is certain, however; if Russia cooperates on this issue, this cooperation will have come despite, not because of, the Biden administration’s undiplomatic approach so far.

Read more:

https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/07/26/so-the-us-wants-help-from-russia-in-central-asia-now/

Read from top