Search

Recent comments

- elon vs kanbra.....

13 min ago - tanked think-tank.....

1 hour 14 min ago - (PAUSE)....

1 hour 40 min ago - repeat....

2 hours 33 min ago - losing....

2 hours 59 min ago - was Pepe sold a pup?....

3 hours 36 min ago - a peace deal....

23 hours 23 min ago - peace now!

1 day 49 min ago - a nasty romance....

1 day 54 min ago - blackmail?.....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

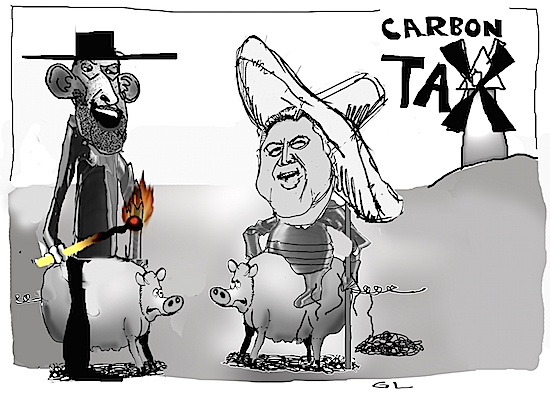

setting our aussie arse on fire...

mad abbott

mad abbott

It was an off the cuff comment after a few drinks, delivered with a belly laugh from a then-senior minister a few years back.

"The difference between Labor's policy and ours is that Julia Gillard introduced a scheme where big polluters paid Australian taxpayers. Tony changed it so that Australian taxpayers pay big polluters," the minister said.

That policy, of course, was the carbon tax.

Introduced in 2012 by the Gillard government, it was dumped by the Abbott government as soon as it came to power and replaced with a more than $3 billion taxpayer subsidy, doled out to applicants that promised to cut carbon emissions.

It'd be funny if it wasn't so tragic.

But the joke now is on us and the tragedy is that it will cost us dearly.

Australian businesses are about to be whacked with a carbon tax.

Not by Canberra, but by Brussels and Washington with the increasing possibility that Ottawa, Tokyo and even London may follow suit, free trade agreements aside.

In the third turn of the wheel, Australian polluters will end up paying foreign taxpayers just for the privilege of exporting their goods.

It's a development that will hurt profits, cost jobs, and hit our export volumes and ultimately the tax take of our own government.

En masse, much of the developed world has begun mulling the idea of putting a price on carbon emissions.

They've also woken to the idea that there's no point introducing a carbon price at home if renegades like Australia don't follow suit.

So, to level the field, goods from any country without a carbon price, such as Australia, will be hit with a carbon tax.

Where did this come from?It's all happened within the space of a few weeks.

One minute, the European Union was announcing its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the next, the United States began making similar noises.

Trade Minister Dan Tehan was aghast.

"Australia is very concerned that the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is just a new form of protectionism that will undermine global free trade and impact Australian exporters and jobs," he said.

The only problem with that argument is that Australia explored the very same option back in 2012 during the carbon tax's brief life.

It was recognised then that corporations may simply shift production offshore to avoid the impost.

Oddly, despite the rapid deterioration in relations between Canberra and Beijing, our largest trading partner may end up as one of our biggest allies in this brewing storm.

For while Beijing just last Friday launched the world's largest carbon market, many believe that at best it will be ineffective and, at worst, a sham.

Its national carbon market has far too many credits, so its carbon price is way too low — around one 10th the EU carbon price.

Not only that, big energy users like steel are excluded.

Unless prices rise dramatically, there is little likelihood of any shift in behaviour or impact on emissions and the fear is that the entire strategy is little more than an artifice.

Why price carbon anyway?Many decisions in our life come down to price.

Even when money isn't involved, we often calculate whether the benefits of embarking on a certain course of action outweigh the potential costs.

When it comes to public policy, we learned long ago that if you want to change behaviour, say to limit the health impact of smoking, one of the easiest ways to do that is to tax goods and services — in the case of smoking, tobacco.

The higher the tax, the fewer individuals will smoke, and the less likely people will take up smoking at all.

That has a double impact on government finances.

The government brings in more revenue, at least until people give up.

More importantly, the health system costs less to run, as a harmful health factor is eliminated.

In the early 1980s, when scientists first twigged that carbon emissions were harming the environment, a group of American economists from Harvard argued that climate change was a cost that was not being recognised.

Not only was it barely visible, the real damage was only likely to be seen in generations to come, way beyond the normal investment horizon.

Back then, they argued that a tax on carbon emissions from all sources was the most efficient way to deal with the problem and, for a while, Washington was in agreement.

It didn't take long, however, for the fossil fuel industry to take up arms against the proposal.

That's when Republicans shifted stance.

Instead of a tax, they preferred a complex market-based trading system that put a price on carbon.

The end result is that the US has never introduced a national system although various US states have carbon prices.

That's all about to change.

Here at home, there was agreement on both sides of the House that a carbon price was needed.

In 1997, then-prime minister John Howard grappled with ways to deal with carbon emissions but took almost a decade before he finally announced an emissions trading scheme in 2006.

Kevin Rudd was elected in 2007 on a platform of addressing climate change but his emissions trading scheme initiative disintegrated under the weight of political bickering between his government, the Coalition and the Greens.

From then on, climate change became toxic as then-opposition leader Tony Abbott flicked the switch from science to ideology.

Does a carbon tax work?There's an easy answer to that.

The ill-fated Australian carbon tax lasted just two years.

But as the graph below indicates, it had an immediate impact.

Emissions dropped almost immediately after it was introduced as businesses moved to technologies that emitted less.

That price signal had an impact.

When it was dumped in 2014, carbon emissions began to rise again almost immediately.

Emissions have since levelled, possibly because of the shutdowns of some large coal-fired power stations during the past two years.

While economists believe carbon taxes are the preferred way to price emissions, politically they've been a hard sell.

No-one likes paying more tax.

According to the World Bank, about 45 countries are covered by a carbon price but few use a carbon tax.

Even the Gillard government's carbon tax was due to revert to a market-priced trading system similar to Europe's.

There's no such reluctance, however, when it comes to whacking a tax on foreigners, as we are about to discover.

What industries will be affected by the border taxes?Mark Carney, the former head of the Bank of Canada and more recently the Bank of England, delivered a blunt assessment of our prospects last week at a conference organised by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors.

Now the United Nations special envoy on climate change and finance, Mr Carney said the world was trending towards enforcing climate policy through trade actionand Australia needed to ramp up its response.

The EU legislation is still in a rough form but will include aluminium, iron, steel, cement, natural gas, oil and coal.

The immediate impact of the carbon border taxes is unlikely to inflict major damage on Australia.

Europe takes just 3 per cent of our total exports and, while our sales to the US are substantially higher, they're not carbon intensive.

The biggest problem will arise if the US imposes carbon border taxes on Chinese made goods.

As our biggest export destination, particularly for iron ore, any action against the Middle Kingdom will have an immediate impact on us.

Given the rapidly escalating tensions between the superpowers, that is highly likely.

Then there is our second biggest trading partner.

Japan late last week announced it was radically revising its emissions target ambitions and announced an accelerated plan to decrease imports of coal and LNG, two of our biggest exports.

The federal government has long been opposed to any form of carbon pricing and has yet to even commit to net zero emissions by 2050.

But the events of the past few weeks may force its hand.

Otherwise, it risks being caught on the wrong side of history at great cost to the economy.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-26/carbon-tax-has-come-back-to-haunt-the-government/100322396

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 26 Jul 2021 - 9:49am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

messy US middle-class transition...

To hear Democrats tell it, a green job is supposed to be a good job — and not just good for the planet.

The Green New Deal, first introduced in 2019, sought to “create millions of good, high-wage jobs.” And in March, when President Biden unveiled his $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan, he emphasized the “good-paying” union jobs it would produce while reining in climate change.

“My American Jobs Plan will put hundreds of thousands of people to work,” Mr. Biden said, “paying the same exact rate that a union man or woman would get.”

But on its current trajectory, the green economy is shaping up to look less like the industrial workplace that lifted workers into the middle class in the 20th century than something more akin to an Amazon warehouse or a fleet of Uber drivers: grueling work schedules, few unions, middling wages and limited benefits.

Kellogg Dipzinski has seen this up close, at Assembly Solar, a nearly 2,000-acre solar farm under construction near Flint, Mich.

“Hey I see your ads for help,” Mr. Dipzinski, an organizer with the local electrical workers union, texted the site’s project manager in May. “We have manpower. I’ll be out that way Friday.”

“Hahahahaha …. yes — help needed on unskilled low wage workers,” was the response. “Competing with our federal government for unemployment is tough.”

For workers used to the pay standards of traditional energy industries, such declarations may be jarring. Building an electricity plant powered by fossil fuels usually requires hundreds of electricians, pipe fitters, millwrights and boilermakers who typically earn more than $100,000 a year in wages and benefits when they are unionized.

But on solar farms, workers are often nonunion construction laborers who earn an hourly wage in the upper teens with modest benefits — even as the projects are backed by some of the largest investment firms in the world. In the case of Assembly Solar, the backer is D.E. Shaw, with more than $50 billion in assets under management, whose renewable energy arm owns and will operate the plant.

While Mr. Biden has proposed higher wage floors for such work, the Senate prospects for this approach are murky. And absent such protections — or even with them — there’s a nagging concern among worker advocates that the shift to green jobs may reinforce inequality rather than alleviate it.

“The clean tech industry is incredibly anti-union,” said Jim Harrison, the director of renewable energy for the Utility Workers Union of America. “It’s a lot of transient work, work that is marginal, precarious and very difficult to be able to organize.”

The Lessons of 2009

Since 2000, the United States has lost about two million private-sector union jobs, which pay above-average wages. To help revive such “high-quality middle-class” employment, as Mr. Biden refers to it, he has proposed federal subsidies to plug abandoned oil and gas wells, build electric vehicles and charging stations and speed the transition to renewable energy.

Industry studies, including one cited by the White House, suggest that vastly increasing the number of wind and solar farms could produce over half a million jobs a year over the next decade — primarily in construction and manufacturing.

David Popp, an economist at Syracuse University, said those job estimates were roughly in line with his study of the green jobs created by the Recovery Act of 2009, but with two caveats: First, the green jobs created then coincided with a loss of jobs elsewhere, including high-paying, unionized industrial jobs. And the green jobs did not appear to raise the wages of workers who filled them.

The effect of Mr. Biden’s plan, which would go further in displacing well-paid workers in fossil-fuel-related industries, could be similarly disappointing.

In the energy industry, it takes far more people to operate a coal-powered electricity plant than it takes to operate a wind farm. Many solar farms often make do without a single worker on site.

In 2023, a coal- and gas-powered plant called D.E. Karn, about an hour away from the Assembly Solar site in Michigan, is scheduled to shut down. The plant’s 130 maintenance and operations workers, who are represented by the Utility Workers Union of America and whose wages begin around $40 an hour plus benefits, are guaranteed jobs at the same wage within 60 miles. But the union, which has lost nearly 15 percent of the 50,000 members nationally that it had five years ago, says many will have to take less appealing jobs. The utility, Consumers Energy, concedes that it doesn’t have nearly enough renewable energy jobs to absorb all the workers.

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/business/economy/green-energy-jobs-economy.html?utm_source=&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=40822

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ##################

the inevitable...

Those of us who have at least an elementary grasp of economics would have been astonished at the reasoning of Trade Minister Dan Tehan during his ABC interview last week on The EU’s proposed carbon levy on imports (the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

The obvious fact is that a carbon levy on trade is inevitable as we approach carbon neutrality by 2050. That is, a decarbonising crunch points is now arriving given the radical differences globally, between the carbon intensity of processing and manufacturing in differing countries. Such differences are becoming intolerable given national (and EU) GHG reduction regimes are radically different in the extent to which they apply a carbon price on different commodities. Such differences will of course unfairly penalise those industries where carbon is priced in line with the transition to a carbon neutral 2050.

With the US and Japan now also taking the first steps to a trade based carbon levy, the necessity of integrating it into our (albeit as yet formulated) 2050 carbon neutrality strategy is obvious. There is no time to be wasted, as Tehan suggests, by going back to the WTO and trying to negotiate some other complex country specific way of integrating national GHG emission regimes (what on earth that might be is hard to imagine).

The reluctance to embrace the CBAM makes no sense given that Australia will, arguably, have most to gain from such a global mechanism. As Ross Garnaut points out, we have the opportunity to be a global renewable energy manufacturing and processing powerhouse based on being able to produce the world’s cheapest solar energy. And as Alan Finkle reminds us, this can in turn turn Australia into a hydrogen driven manufacturing and exporting powerhouse. That prospect is being enhanced by AEMO’s plan to make the Australia power grid wholly renewable by 2025 – which happens to fit neatly with the EU’s planned start for its trade based carbon levy in 2026.

Thus, a carbon levy on exports would deliver the essential competitive underpinning for such energy investment projects as the $100 billion the Western Green Energy renewable energy hub. It would also put us in the front of the queue for hydrogen exports to Japan. That is, a levy would ensure that low cost high polluting processing and manufacturing in China, India and elsewhere will be less competitive.

In the shorter term the CBAM poses little threat to Australian exports. Its application to cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilises and electricity – as the Australian Industry group have pointed out – will have little effect on our trade with the EU given it is minimal in these products. Moreover, the CBAM regime is to incorporate a parallel reduction of free carbon credits allocated to EU heavy industries to protect them from carbon leakage – trade generated by exporters to the EU which are competitive from not being subject to a carbon tax.

In the medium term a global rollout of an export carbon levy can only help accelerate the decarbonising of our power sector and the re-creation of a low carbon heavy industry sector. However, the indirect effect of a trade based carbon levy on our coal exports needs to be examined given, presumably, its the unspoken factor in our Government’s response to the CBAM. If such a tax were to be extended to such exports, Australia’s efficiency as a miner would indicate any carbon generated in the extraction process would be less than our competitors. More to the point is whether a carbon export levy would accelerate the transition away from coal. However, the transition from coal to renewables is and will be driven by the carbon price. In the EU its rise – currently around 50 EU or $AU80 – is a reflection of its accelerating carbon neutrality goals. That acceleration is and will be evident for other countries (China’s carbon price is estimated to be only around 3 EU) as 2050 approaches and with this will inevitably come an adjustment mechanism for international trade.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/jeremy-webb-ready-or-not-a-carbon-price-on-exports-is-coming-to-australia/

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW Ô˚˚˚˚˚˚˚˚˚••••••¶¶¶¶¶¶§§§§§§!!!