Search

Recent comments

- was Pepe sold a pup?....

21 min 57 sec ago - a peace deal....

20 hours 9 min ago - peace now!

21 hours 34 min ago - a nasty romance....

21 hours 40 min ago - blackmail?.....

1 day 11 min ago - ukraine's agony has not started yet....

1 day 17 hours ago - all defeated.....

1 day 17 hours ago - beyond crime.....

1 day 18 hours ago - the end....

1 day 18 hours ago - odessa....

1 day 20 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a sad sad reality...

sad

sad

When world leaders like Joe Biden and Boris Johnson descend on Glasgow for the world's most significant meeting on climate in years, they could well come face to face with a billboard designed by an Australian comedian.

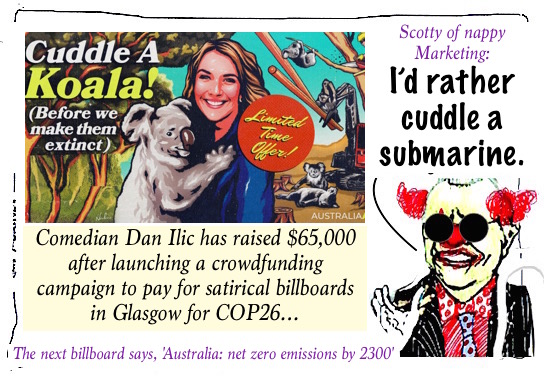

Key points:Comedian Dan Ilic has raised $65,000 after launching a crowdfunding campaign to pay for satirical billboards in Glasgow for COP26

The federal government has yet to decide who will represent Australia at the global climate conference

Mr Ilic says he will use the excess funds to launch 'JokeKeeper'

Dan Ilic bought the billboard space for $12,225 and with the invoice hovering over him, he launched a fundraiser to help pay for it on Monday.

The goal of the campaign is to satirise Australia's climate commitments.

"Just to tell people there in Glasgow that the people there at the talks representing Australia, don't necessarily represent Australians," said Mr Ilic.

Twelve hours after asking for help footing the bill, he raised his goal and today the figure stands at over $65,000.

"I've kinda had to change the scope of the campaign, it looks like we could be close to projecting that billboard onto the SEC Armadillo, which is the conference centre where the COP is being held," he told the ABC's The World Today program.

He already has two billboard designs, one in the style of an ad promoting tourism to Australia.

"We've got one that says, 'cuddle the koala before we make them extinct'," Mr Ilic told the ABC's The World Today program.

"The next billboard says, 'Australia: net zero emissions by 2300'."

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 Sep 2021 - 6:21pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

how adorable...

Dwindling habitat. Climate change. Mega-bushfires. Koalas face dire threats, yet politicians continue to obfuscate.

By Stephanie Wood

Every summer for a decade now, the curious photos have surfaced: a koala gulping water from a firefighter’s bottle, a koala drinking from a watering can, another on its belly trying to slurp from a swimming pool. By late 2019, images were popping up daily: a koala clinging to a bike as a cyclist tipped water into its mouth, another drinking from a pot of water while a dog stood nearby. In northern NSW near Moree, one was photographed in the middle of a road after rain, its curling pink tongue licking a puddle.

The comments came from around the world: “OMG, so cute” and “How adorable!”

But there was something unsettling about the images; koalas don’t drink water, they get the moisture they need from gum leaves. Don’t they? Even scientists and koala experts who knew the species was in peril were unlikely to have realised just how portentous the images were.

In spring 2019, the fires started.

There was nothing cute about the new images, which came in a flood. Koalas with bandaged paws and scorched ears nestling in laundry baskets in a wildlife volunteer’s lounge room. A huddled koala trying to drink from a Kangaroo Island dam, the charred carcass of another nearby. A woman stripped down to her bra running out of a blaze near Port Macquarie holding a koala in her shirt; if you watched the video, you heard the koala mewling in pain as the woman doused it in water.

As the imagery spread and the world’s attention focused on this devastating escalation of the koala crisis, the animal became a global symbol of environmental grief and fear. Prayers and messages of love rained down. So did money. Port Macquarie’s Koala Hospital created a GoFundMe account with a $25,000 goal and got nearly $8 million. From Kazakhstan to Kentucky, people sewed mittens for burnt paws. A cosmetics firm made eucalyptus-scented, koala-shaped soap to raise funds. A little boy in Massachusetts moulded the marsupials in clay and his parents gave one to every person who donated more than $50 to the cause. A friend in London couldn’t stop crying. “You’re not looking at koala pics again, are you, Mum?” her daughter asked.

We say we love them, but in the 230 years since the arrival of the First Fleet, we have systematically and thoughtlessly killed koalas. In June 2020, a bipartisan NSW Parliament upper house inquiry into koalas declared that without urgent action, the marsupial would be extinct in the state by 2050. The federal government is assessing the NSW, ACT and Queensland koala populations for uplisting from their current “vulnerable” status to “endangered”. (A vulnerable species faces a high risk of extinction in the wild; an endangered species has a very high risk. The koala is not listed as vulnerable in Victoria and South Australia, where there are complex factors including inbreeding and over-population.)

At the time of white settlement, it is believed there were millions of koalas across our continent. Two centuries later, before the 2019-20 fires, the most authoritative study available estimated 331,000 koalas remained in the wild nationally, 79,000 of which were in Queensland and 36,000 in NSW. But koala counting is a notoriously difficult exercise and the 2012 study, led by University of Queensland conservation biologist Dr Christine Adams-Hosking and drawing on the research of a number of koala experts, noted that in Queensland, population estimates ranged from 33,000 to 153,000, and in NSW from 14,000 to 73,000.

But if the numbers aren’t firm, one thing is: even before the fires, koala populations had been declining precipitously. Studies carried out in 2020 by Dr Steve Phillips, principal research scientist at environmental consultancy Biolink, found that in the past two decades, Queensland had lost half its koalas, and NSW a third. Experts are still trying to tally the full extent of Black Summer’s carnage but University of Sydney research found 61,000 koalas nationally and 8000 in NSW were injured, displaced or died during the fires.

We did this. Since settlement, our needs have always trumped those of koalas. We needed the land their trees were on. Sometimes we shot them to eat. In an article in The Sydney Morning Herald in June 1851, the author noted that Aboriginal people called the creature a “kola” and settlers described it as “the native bear or monkey”. It was an animal with a “singular aspect”, he wrote, “its appearance is a sort of caricature upon gentlemen of the legal profession with their wigs on. It is said to be good eating, but is not frequently met with …”

“The response to the majority of recommendations were ‘Support in principle’ or ‘Noted’, which to me is saying, ‘We’re doing nothing’.”

We wanted their furs. From the late 19th century to the end of the 1920s, hunters slaughtered up to eight million koalas nationally to supply a voracious international fur market. Most went to England and the US, where they were described as “wombat fur” and often became part of that Jazz Age wardrobe essential, the fur collar wrap coat. By the late 1930s, the animal was considered extinct in South Australia and critically depleted elsewhere.

Still we wanted more: more land for farms and tree plantations and highways and developments of massive houses with manicured gardens. Developers saw dollar signs, their bulldozers kept moving. With all that came fast cars, feral animals, family pets and disease. A submission from a koala activist in northern NSW’s Ballina to the NSW parliamentary inquiry listed in wretched detail the fate of some local creatures: “Healthy breeding female, hit by car”; “Female, dog attack, dead”; “Male, retrovirus, ulcers in mouth and throat, hadn’t eaten for probably [two] weeks, maggots down throat while still alive, found sitting on a road after a storm”.

Above all else, our insatiable needs have led to the greatest threats koalas face: climate change and its handmaidens, more extreme droughts and bushfires. But despite the international spotlight the 2019-20 fires threw on the urgency of the species’ plight, one year on, governments have taken little meaningful action to protect the marsupial and its habitat.

The NSW Environment Minister, Matt Kean, says he wants to double koala numbers in the state by 2050 but in January his government announced it would fully commit to only 11 of the upper house inquiry’s 42 recommendations designed to protect koalas. Conservationists and koala scientists were horrified. “It’s really disheartening that the response to the vast majority of recommendations were ‘Support in principle’ or ‘Noted’, which to me is saying, ‘We’re doing nothing’,” Port Macquarie Koala Hospital clinical director Cheyne Flanagan says. “In koala circles, everyone’s disgusted.”

Meanwhile, for months through 2020 the koala became a political football after the Deputy Premier and National Party Leader, John Barilaro, staged a failed rebellion against his own government over koala policy. The result of the subsequent political wrangling was that, by the end of the year, policy to protect the species was weaker than it had been at the start.

Experts also point to the federal government’s shilly-shallying. Key national measures to protect the koala are either out of date or yet to be completed. “The koala was listed as a vulnerable species by the federal government in 2012; seven years later, we’re still waiting for a national koala recovery plan,” says Biolink’s Steve Phillips.

And what of the three billion other animals killed or displaced by last summer’s fires? One million lumbering wombats. More than 100,000 echidnas. Millions of kangaroos and wallabies; bandicoots, quokkas and potoroos. A terrible number of birds, lizards and frogs. The uncounted pretty beetles, butterflies and bugs. Well, it’s hard to spare too much emotional energy for a frill-neck lizard. But a koala … we can mourn a koala.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/national/how-good-were-koalas-a-national-treasure-in-peril-20201203-p56kac.html

koala capers...

There are a couple of city cycleways that come to an abrupt and unannounced end. You’re happily tootling along, with the wind in your hair and the love in your heart when, whammo, you’re out in honking rush-hour traffic. All at once it’s you against the predators, fighting for life. This is how the Campbelltown koalas are going to feel when Lendlease has its way with them.

Koalas, as you know, are vulnerable. In June 2020, a NSW Upper House inquiry, having heard much learned scientific evidence, found that without urgent action “the koala will become extinct in NSW before 2050”. The Campbelltown koalas are the last chlamydia-free population in Greater Sydney and one of the few thriving colonies in the state.

You might think all those things would stop even the baddest of baddies fighting in court for the right to endanger these koalas further. Yet Lendlease has just done exactly that, successfully defending itself against a legal attempt by Save Sydney’s Koalas to force it into better manners.

The development in question is Lendlease’s Figtree Hill, an immense and controversial redevelopment of a large chunk of the historic Mt Gilead farm south of Campbelltown. Some 1700 houses are planned for stage 1 and an unknown number for stage 2, some four times as big.

None of this is good. Destroying farmland to peripheralise the poor is so last century. Out on the urban fringe where trees have fallen to profit, summer temperatures will approach 50C. Air conditioners will be permanently on. Public transport is non-existent. The nearest train station is a 10-minute drive. Nothing is walkable. So families that can least afford it need two or three vehicles apiece. All that gas, all that energy, all that carbon.

But worse still is fighting to render a beloved and vulnerable species more vulnerable still.

Naturally, the official version makes everything hunky dory. Campbelltown Council and the local planning panel (which approved the DA last December) insist the development is “consistent with” both the 2020 Chief Scientist’s report and the Campbelltown Koala Plan of Management.

Similarly, Lendlease’s website seduces potential residents with talk of rolling hills and “vast untouched” bushland; a pretty koala underpass beneath Appin Road has the dreamy focus of a Harold Cazneaux bush idyll.

That’s the spin. But many are unpersuaded. Investor Australian Ethical, for example, supports other Lendlease projects but rejects Figtree Hill because it “will introduce new threats to the local [koala] colony”. Environmentalist and former Australian of the Year Jon Dee says this development could destroy Lend Lease’s “very good sustainability reputation”.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/environment/sustainability/thousands-of-homes-among-their-gum-trees-the-assault-on-sydney-s-last-healthy-koalas-20211014-p5905h.html

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW√√√√√√√√√√