Search

Recent comments

- waste of cash....

2 hours 27 min ago - marles' bluster....

2 hours 49 min ago - fascism français....

2 hours 53 min ago - russian subs in swedish waters....

3 hours 32 min ago - more polling....

3 hours 38 sec ago - they know....

7 hours 48 min ago - past readings....

8 hours 48 min ago - jihadist bob.....

8 hours 54 min ago - macronicon.....

10 hours 48 min ago - fascist liberals....

10 hours 49 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the lost long weekend…...

On the evening of November 9, 1989, thousands of East Germans—including a 35-year-old chemist named Angela Merkel—peacefully crossed into West Berlin amid chaos and the confusion at the Berlin Wall. Within hours, the gates of the most notorious symbol of the Cold War opened for good, as champagne flowed and jubilant Germans with pickaxes began to lop off large chunks of the wall.

1989-2001: America’s Long Lost Weekend

From the fall of the Berlin Wall to 9/11, we had relative peace and prosperity. It was an opportunity to salve some festering national wounds. We squandered it completely—and helped give rise to the crises we’re dealing with today.

It was midafternoon at the White House when Brent Scowcroft, the national security adviser, walked into the Oval Office to tell George H.W. Bush that initial reports suggested the wall had been opened. But any public jubilation was tempered by the guiding principle of Bush’s career—prudence. As Bush biographer Jon Meacham recounts in Destiny and Power, “Borrowing a phrase from Scowcroft, Bush was determined not to ‘gloat.’” Meeting with reporters in the Oval Office, Bush struck a tone so subdued that CBS reporter Lesley Stahl said, “This is a sort of great victory for our side in the big East-West battle, but you don’t seem elated.” Bush’s response at this epic turning point in modern history: “I’m not an emotional kind of guy.”

Even when the president met with Mikhail Gorbachev in Malta in December of that year to symbolically ratify the end of the Cold War, Bush’s words were muted. For more than four decades—through proxy wars in Korea and Vietnam and an eyeball-to-eyeball nuclear confrontation during the Cuban Missile Crisis—the world had teetered on the brink. But throughout his presidency, Bush never displayed half the enthusiasm over the collapse of communism that he had as a Yale first baseman every time his team defeated Harvard. Bush’s restraint has been praised by foreign policy experts—but it also deprived Americans of a stirring moment of national unity over the end of the Cold War and the fears of nuclear Armageddon.

In the current era of pandemic, polarization, insurrection, war in Ukraine, dramatic climate change, and the fraying of democracy, it is difficult to conjure up what the United States was like during the glorious, nearly 12-year period that began on November 9, 1989. With Russia on the ropes and China still emerging from its Maoist slumber, the United States dominated the world. As Michael Mandelbaum, an emeritus professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, asserts in his new book, The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy, “The international position that the United States assumed in the wake of the Cold War was one that no other country held or had ever held.” And, yes, that includes ancient Rome and the British Empire.

This period also brought with it, for the most part, boom times at home. Despite a short recession in 1990 and a dot-com stock market collapse in 2000, the era was marked by a steadily declining unemployment rate, which hit 4 percent in 2000, the lowest figure in three decades. The millennium ended with balanced budgets—in fact, Bill Clinton bequeathed George W. Bush a $236 billion surplus—and widespread talk of paying off the entire national debt. In April 2001, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan—no fan of “irrational exuberance”—predicted in a major address, “While the magnitudes of future federal unified budget surpluses are uncertain, they are highly likely to remain sizable for some time.”

Of course, there were festering problems—race relations, growing inequality, the rise of the culture wars, politics becoming a blood sport, and a nation that worshipped wealth as if we had returned to the Gilded Age. But for most Americans who were alive then, the 1990s were the best years of our lives. No fears of nuclear war, a sense that permanent prosperity was at hand, and a smug feeling that the world was about to enter into its second American Century. Titanic, the highest-grossing movie of the 1990s, said it all—we were awash in luxury and bristling self-confidence until we hit the iceberg on September 11, 2001.

Looking back from the perspective of this dismal decade, we can now see the glory years of the post–Cold War United States as a tragedy. So many problems today (massive income inequality, global warming, Vladimir Putin’s bellicose one-man rule in Russia, and the threat of authoritarianism here at home) could have been lessened by smart and aggressive government action during these 12 years of peace and prosperity. Instead, the period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11 was a time of missed opportunities.

Despite the political appeal of Fleetwood Mac singing “don’t stop thinking about tomorrow,” the dominant ethos of the era was Think Small. Part of it was the status quo leadership of the era—which, for the most part, included Bill Clinton—and part of it was a restive electorate who wanted change but couldn’t define what that meant. But the conceptual failure transcended politics and elections. This was the Seinfeld age—12 years about nothing beyond an ill-defined belief in a glorious technological future. Part of the problem was that Americans, after more than a decade of anti-government rhetoric under Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, had a truncated view of what might be achieved by an ambitious president. When Clinton declared in his 1996 State of the Union address, “The era of big government is over,” he was reflecting the polls and public sentiment.

There is a larger point beyond regret in revisiting these lost years of post–Cold War triumphalism. This era serves as a cautionary reminder that if the voters demand little of government beyond lower taxes, that’s about all they are going to get. The 1990s also brought with them a reminder of the folly of expecting the free market and profit-seeking corporations and financiers to uplift society and transform the globe. To understand where the nation went wrong during this pivotal 12-year-period, I will examine the might-have-beens in three crucial arenas—the economy, the world, and American society.

THE ECONOMY

The 1990s and early aughts were a high point of government by the elite and often for the elite. There was, in particular, a well-bred insularity to the two Bush presidencies—a sense that the United States was populated by people (mostly men) who came from the right families, went to the right schools, and ran the right companies.

In his acceptance speech at the 1988 Republican National Convention, Bush Sr. tried to convince conservatives of his faith in Reaganism by declaring, in words crafted for him by Peggy Noonan, “Read my lips: No new taxes.” The line worked, as Bush crushed Michael Dukakis in the 1988 election with the entire GOP behind him. But Bush’s old-fashioned balanced-budget ethos (which had once prompted him to denounce supply-side theory as “voodoo economics”) prevailed in late 1990. Preoccupied with the planning of the Gulf war to liberate Kuwait after Saddam Hussein’s invasion, Bush went along with a congressional budget compromise that raised the highest marginal tax rate from 28 percent to 31 percent. It may have been responsible governance, but it came at a price the country is still paying. House Republicans led by Newt Gingrich revolted when Bush agreed to raise taxes. Grover Norquist’s anti–new-tax pledge became religious gospel for congressional Republicans. And with a few very minor exceptions, Republicans in Congress have not backed a single tax increase in three decades.

With the country shakily recovering from a recession, nothing about Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign suggested a continuation of the green-eyeshade, cut-the-deficit zeal of the Bush administration. But the great turnabout came in a meeting in the Governor’s Mansion in Little Rock about two weeks before Clinton was even inaugurated. Bush aides, the day before, had leaked the news that deficits were projected to run over $300 billion a year throughout Clinton’s first term. As Bob Woodward tells it in The Agenda, Clinton exploded as he was told again and again by his mainstream economic advisers that Wall Street needed to be wooed with deficit reduction. Red-faced with anger, Clinton bitterly asked, “You mean to tell me that the success of my program and my reelection hinges on the Federal Reserve and a bunch of fucking bond traders?”

This was the moment when the ambitious Keynesian dreams of the Clinton campaign were lost. Had the president followed his own initial instincts and the advice of his political advisers, his economic agenda would have been far bolder than a half-hearted attempt at passing a stimulus package and trying and failing to enact a health care plan. By late 1993, according to Woodward, a frustrated Clinton was mockingly describing himself as a Dwight Eisenhower Republican, which underscored how far to the center he had drifted.

The Clinton years brought with them liberal governance by those with high SAT scores. Few in the Clinton orbit—other than the president himself—had a visceral sense of the white working class, which was once a dominant element in the New Deal coalition. That may help explain these economic numbers: From 1991 to 2000, the incomes of those in the top 5 percent rose at an annual rate of 4.1 percent. For those in top 20 percent, it was 2.7 percent annually. And for everyone else (80 percent of the working population), incomes grew at a stagnant rate of 1 percent. This was economic inequality on the march.

Clinton always had a secondary political agenda—to belatedly defuse Ronald Reagan’s attacks on the Democrats. For all of Clinton’s campaign talk about “building a bridge to the twenty-first century,” much of his administration was backward-looking in an effort to refight and finally win the battles of the 1980s.

That explains the hard-line 1994 crime bill (championed at the time by Senator Joe Biden), and Clinton signing 1996 legislation that revamped and toughened welfare. The text of a 1996 Jules Feiffer cartoon captured the essence of this side of Clinton: “I am morally troubled by the welfare reform bill because it punishes the weak ... who, come to think of it, don’t vote, while everyone who resents them does! So I better hold my nose and sign the welfare reform bill. Because if I don’t get reelected, who’s going to stand up for the poor?”

Despite the opposition of labor, Clinton reluctantly endorsed the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico, negotiated by the Bush administration, late in the 1992 campaign. Once in office, though, Clinton emerged as an ardent free trader, calling more than 200 House members to push for ratification of the treaty. George Stephanopoulos, in his White House memoir, All Too Human, brooded at the time that NAFTA was “a stick in the eye of our most loyal labor supporters.” Signing NAFTA in the Oval Office in late 1993, Clinton warbled, “Good jobs, rewarding careers, broadened horizons for the middle-class Americans can only be secured by expanding exports and global growth.” As for those inevitably left behind by globalization, Clinton offered these reassuring words, “Every worker must receive the education and training he or she needs to reap the rewards of international competition rather than to bear its burdens.”

Globalization coupled with vast technological change were, of course, unstoppable forces, and crude protectionism would have been as ineffective as King Canute confronting the tides. But the failure of the Clinton administration and free-trade Democrats was rooted in an inability to understand how entire communities in the industrial Midwest would be devastated by the wrenching transition. “Of course, everyone knew there would be losers from free trade,” said Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who served on Al Gore’s staff during the Clinton years. “But they believed that trade adjustment assistance and job training would help them get over it. That was the great fallacy. Steelworkers didn’t want to become X-ray technicians, even if they could.”

Long-term thinking was not completely abandoned in Washington, but the emphasis was on the wrong future problems. There was an obsession among elite policymakers in both parties that the Social Security Trust Fund would not be able to make full payments in the 2030s without additional subsidies from Congress. (That is still the case.) But somehow this was regarded as an urgent national problem during Clinton’s second term. Confronted with a growing Republican chorus demanding major tax cuts, Clinton in his 1999 State of the Union address responded with the most politically appealing counterargument that he could muster: “Save Social Security First.” The president proposed that 60 percent of the budget surplus for the next 15 years should go directly into the trust fund. Clinton argued, “We should put Social Security on a sound footing for the next 75 years.”

But thanks to George W. Bush, nothing in Washington was left on a sound footing—even before the September 11 attacks. In June 2001, Bush proudly signed a $1.35 trillion tax cut that sprinkled most of its bounty on the wealthiest Americans, and he enacted another alms-for-the-rich rate reduction in 2003. Even without Bush’s maladroitly managed wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Clinton’s gritted-teeth austerity was wiped out as soon as the Republicans squeaked into the presidency.

THE WORLD

Looking back on the heady period after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, it might be tempting to ask, “Who lost Russia?” The truth was, of course, that Russia was never ours to lose. But dating back to the George H.W. Bush years, the United States consistently, through shortsightedness and neglect, took steps that undermined Russia’s transition to democracy and a healthy market economy. Economist and Russia expert Anders Aslund has long argued that a pivotal moment came in November 1991, when the United States and the other G-7 countries refused to forgive the international debts of the defunct Soviet Union. This was a story that never won front-page coverage in the United States, but it stung in Moscow. In a 2000 paper, Aslund argued that the G-7’s only “interest was to secure their claims on the Soviet Union, which they also did in an untenable way. The young Russian reformers were shocked and dismayed by the G-7’s total disinterest in their reform plans.”

READ MORE:

https://newrepublic.com/article/166758/america-1989-2001-foreign-policy-lost-weekend

FREEEEEE JULIAN ASSANGE PLEEEEEEASE.......

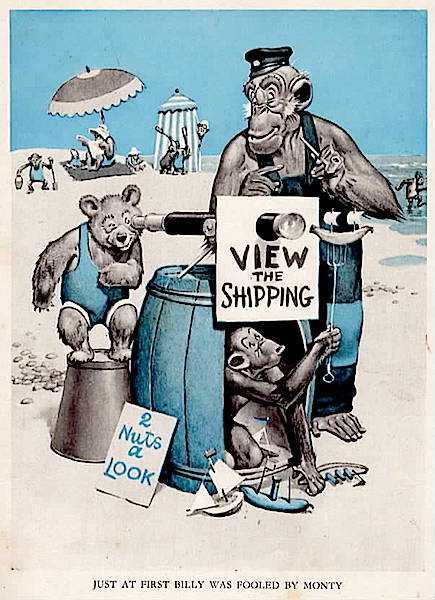

The image at top from Lawson Wood's Annual shows the monkeys tricking the bear... but not for long enough though. This is used here by Mr Leonisky, cartoonist since 1951, as an allegory of the US monkeys playing funny buggers on Russia-the-bear, who soon becomes aware of the deception...

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 Jun 2022 - 9:52am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

not enough water to make a light soup…..

Global aid group Oxfam has eviscerated the G7 countries for pledging a pittance to fight the global food crisisThe G7 countries are “leaving millions to starve and cooking the planet,” global aid group Oxfam’s head of inequality policy Max Lawson has declared in a statement issued on Tuesday condemning the mere $4.5 billion the industrialized nations have pledged to fight the worst hunger crisis in decades.

Lawson argued that “at least $28.5 billion more” was needed to “finance food and agriculture investments to end hunger and fill the huge gap in UN humanitarian appeals.” G7 countries have pledged about $14 billion to fight global food insecurity this year, including the amount pledged on Tuesday.

However, it’s not clear how much of that money has actually been distributed to its intended recipients. While the US Congress passed a major weapons and aid package for Ukraine last month that included $5 billion to “fight global hunger,” none of the hunger money had been sent out as of this past weekend, according to Politico.

With even wealthy G7 countries facing economic difficulties in the wake of two years of Covid-19 shutdowns, the Oxfam rep suggested there were other ways they could fight hunger among the world’s most vulnerable. “They could cancel debts of poor nations” or “tax the excess profits of food and energy corporates,” he argued, or “ban biofuels,” which divert crops that could be used for food to producing energy instead.

Most importantly they could have tackled the economic inequality and climate breakdown that is driving this hunger. They failed to do any of this, despite having the power to do so.

Lawson noted that while the world faces its worst hunger crisis “in a generation,” the rich have seen their profits soar at the same time. “Corporate profits have soared during Covid-19 and the number of billionaires has increased more in 24 months than it did in 23 years,” he said, noting that the food industry alone has produced 62 new billionaires and calling the hunger emergency “big business.”

The UN World Food Program begged the G7 nations to “act now or record hunger will continue to rise and millions more will face starvation” last week, declaring that it had a plan - “the most ambitious in WFP’s history” - requiring $22.2 billion to “both save lives and build resilience for 152 million people in 2022.”

It’s not clear where they obtained that figure, as the G7 countries themselves have said that 323 million people are on the brink of starvation because of this year’s dire food crisis, with 950 million expected to go hungry in total in 2022.

READ MORE: West makes vow on Russian food exportsWhile the G7 countries have been reluctant to open their wallets to solve world hunger, tens of billions have been pledged in economic and lethal aid to Ukraine, where the war has interrupted a wheat harvest that typically accounts for a fifth of the world’s “high-grade” wheat and 7% of all wheat. The UN’s food program normally buys half of its grain from the country.

Exacerbating the supply crisis are record droughts around the world, with East Africa particularly affected. One person is estimated to die of hunger every 48 seconds in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia, where the droughts are the worst in 70 years, according to Oxfam.

READ MORE:

https://www.rt.com/news/558033-oxfam-slams-g7-global-famine/

READ FROM TOP.

PLEASE, DON'T BLAME RUSSIA FOR THIS.....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW......................