Search

Recent comments

- patriotism....

2 hours 42 min ago - belittling russia......

3 hours 9 min ago - Запад толкает Украину на последнюю битву....

3 hours 23 min ago - fourteen points....

3 hours 32 min ago - der philosophische glaube....

3 hours 43 min ago - seriously?...

3 hours 57 min ago - AfD....

4 hours 25 min ago - undesirables...

4 hours 41 min ago - assistant spies......

5 hours 6 min ago - brics.....

8 hours 14 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

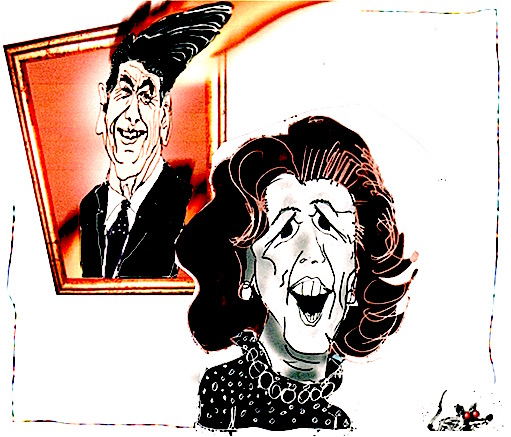

the bad economic fall-out from the two rentier capitalists of the 1980s...

This book by Thomas Piketty was first published in 2014 and became an instant best seller. It had taken the author some 15 years to research and complete, and deserves a detailed attention and analysis rather than the usual one-off, production-line tracts which are read and instantly forgotten. Piketty describes the end of an old epoch, the rise of the new – the golden age of welfare-capitalism, Le Trente Glorieuses, the Keynes/Beveridge consensus, call it what you will, circa 1945-1975 – and the re-emergence of a second rentier capitalism regime which began the early 1980s.

Using apposite literary references to writers of the first gilded age he quotes:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Jane Austen – Pride and Prejudice

An immortal sentence which says a thousand words. Such was the moral zeitgeist in Europe during the 19th century; Piketty then drives home the point by adding Honorė De Balzac’s novel Pėre Goriot which focuses on the decadent, money-grubbing dispensation of the Bourbon Restoration. Arguably the moral climate hasn’t appreciably changed in our money worshipping age, but the origins of a ‘good fortune’ has. What concerns Piketty, is the source and nature of this ‘good fortune’ which is so sought after, and also where this latest historical configuration is leading.

The world of Austen and Balzac lasted from roughly 1870-1910 representing the first belle époque of rentier capitalism. The system[1] involves ownership of capital assets – in the 19th century mainly land – and living from the rent (in the broad sense) derived from these assets. Latterly, in what is the second golden age of the rentier regime, the capital asset base has changed from simply land to ownership of financial assets, real estate, stocks and bonds and high corporate incomes.

This is not to say that the old rentier classes have ceased to exist, but they have been supplemented by an emergent new class of hedge-fund managers, corporate executives and CEOs, investment bank chiefs, and former entrepreneurs like Bill Gates – which for a better term, we will call the working rich. As Piketty explains:

The top decile (10%) always encompasses two different worlds: the 9% in which income from labour predominates, and the 1% (of true rentiers) in which income from capital becomes progressively more important.”

Thus, former entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates cease to live off their labour as their accumulation of capital enables them to enter the genuine rentier class, the class able to live off capital. The new rentiers would also include Heiresses such as Liliane Bettencourt of L’Oreal and Paris Hilton, neither of whom have ever done a day’s work in their lives. Consequently, the rentier class grows with every passage of successful entrepreneurs entering its ranks. It might also be added that there has also been the rise of a parasitic speculative financial sector class who make a living by purchasing and selling various asset classes, in the main stocks, property and bonds.

Historically speaking Piketty asserts that the trend line for return on capital has been 4/5% – this has been an historical fact rather than some inexorable law – whereas growth has lagged at 1 to 1.5%. This process is expressed in the equation r>g where r is return on capital and g is growth. Accumulated capital (as stock) has tended to increase as a ratio to income (as flow). Moreover, the distribution of national income (GDP) has become increasingly skewed to the top decile. According to Piketty this has been a technical as well as a social/political process the consequences of which will be profound.

When the rate of return on capital significantly exceeds the growth rate of the economy (as it did throughout history up to and including the 19th century and as is likely to be the case in the 21st century) then it logically follows that inherited wealth grows faster than output and income … Under such conditions, it is almost inevitable that inherited wealth will dominate wealth amassed from a lifetime’s labour by a wide margin, and that the concentration of capital will attain extremely high levels – levels potentially incompatible with the meritocratic values and principles of social justice fundamental to modern democratic societies.

Read more:

https://off-guardian.org/2019/02/17/a-taxing-question-re-reading-piketty/

- By Gus Leonisky at 17 Feb 2019 - 6:51pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

that this is happening here is unbelievable...

“This is not normal. We are in France, one of the oldest and best democracies in the world,” says Fiorina Jacob Lignier, who lost her eye at a demonstration in Paris on December 8. "We usually condemn from afar other countries where this occurs, that this is happening here is unbelievable."

Lignier, a 20-year-old philosophy student, traveled from the northern city of Amiens to march on the Champs-Elysees to protest against fuel taxes with her boyfriend, Jacob Maxime.

He told RT that they were marching with a column of peaceful demonstrators, when a group of masked radicals began to vandalize a shopfront more than 50 yards away.

The police “began shooting ‘Flash Balls’ and throwing grenades in all directions,” during which the couple spent two hours “penned in between a line of gendarmes and a wall, with no chance to flee.”

Lignier said the last thing she remembers was the cries of cops clearing the way for firemen, then a gas grenade hit her on the head, and she was on the ground.

When she woke up, her nose was broken, her face swollen from fractures, and she couldn’t see through her left eye. Over the next 16 days, Lignier underwent two surgeries, and is still waiting for two more.

Read more:

https://www.rt.com/news/451632-france-yellow-vests-eye-hand-injuries/

This item could appear unrelated to the "economic bastards of the 1980s", but Macron-le-Con could be declared the son of those two mongrels: Reagan and Thatcher. The "gilets jaunes" are easily victims of the "far right" thugs agents destructors/provocateurs, which to say the least in France could be aligned with the Macron government to shame the Yellow Vests. Not a new trick, already exposed on this site.

out of the loop...

In English:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=220&v=hbnzQtLS4T8

Yanis explains clearly how the banking capitalist system has highjacked "democracy". Not only we live in a "technocracy" we live in an "oligarchic technocracy" where the super-rich and the governments who work for them use technology to keep us out of the loop, even when we vote...

AND THE CONTROLLERS OF THE MONEY WILL FIGHT TOOTH AND NAIL TO KEEP VAROUFAKIS OUT OF THEIR POLITICAL GAMES...

making money from the lounge chair...

More than 1,200 billion euros were paid in dividends by the 1,200 largest listed companies. 2018 was the best year in history for shareholders, a better result than 2017, which was already a record year.

According to figures provided by investment management firm Janus Henderson from the results of the 1,200 largest publicly traded companies, 2018 is a record year for paying dividends to shareholders worldwide.

In 2018, companies paid a total of nearly $ 1,370 billion (€ 1,200 billion), an increase of 9.3% over the previous record; 2017, when 1,252 billion dollars (1,105 billion euros) had ended up in the pockets of shareholders.

To explain these good performances, the financial institution puts forward several factors such as the lowering of taxes in the United States, but also the evolution of the policy of companies in the mining, oil and banking sector that would have "managed" their dividend payments, after a period when their dividends were low or non-existent". Another reason cited is the large technology companies that "are increasingly adopting a culture of paying dividends".

Read more:

https://francais.rt.com/economie/59256-avec-1370-milliards-dollars-divid...

Translation by Jules Letambour.

Read from top. Were you working for wages, you made nothing more — except loose traction...

first of april tax...

Context is everything when we come to view events in history, both recent and ancient. Working class writers and participants in struggle should always be encouraged to document their experiences lest the critical role played by ordinary people in the advance of society is forgotten, or more likely hidden. The Poll Tax revolt was a mass working class rebellion against a Prime Minister who had appeared unbeatable and unstoppable. She had been daubed ‘The Iron Lady' across Europe due to her reputation for fighting political foes domestically and internationally.

Mrs Thatcher became the UK's first female Prime Minister in 1979 on the back of significant industrial unrest caused by the sitting Labour Government's policy of wage restraint on lowly paid public workers who had no alternative but to fight for better pay. What became known as the ‘Winter of Discontent' over 1978-1979 was the breeding ground for Thatcher to portray herself as a ‘strong' woman who could sort out Britain's problems, particularly high unemployment. The poster that defined that election was ‘LABOUR ISN'T WORKING' with a long queue of people depicted outside an unemployment office. The official rate of unemployment was sitting at 6%.

Thatcher was a brutal monetarist who believed in cutting taxes for the rich and wealthy on the basis that some of the wealth created would eventually ‘trickle down' to the poor and low paid. It is a theory as robust as the tooth fairy tales but slick advertising and promotion convinced many it would work. Deciding to turn the UK from a manufacturer of goods into a supplier of services Thatcher began a de-industrialisation process that saw steelworks, shipyards, coal mines and car factories reduced in size and often closed. The Finance Capital wing of the Tory party was dominant. The market trading yuppies and expert sellers of stocks and shares were in the ascendancy. Lots of money was being made but nothing of value was being made [created].

READ MORE: UK Absolute Child Poverty Hits 3.7m Amid Brexit Chaos, Jumps 200,000 In One Year

From 1979 to 1982 Britain was subjected to a concerted policy of industrial vandalism under the cold and callous rule of Thatcher. The high unemployment of 6% in 1979 which gave rise to the ‘Labour Isn't Working' poster became mild compared to the 12% unemployment rate under Thatcher. She and her Government were increasingly unpopular and heading for electoral annihilation. They had fallen to only 30% support in opinion polls. Talk of deposing her from leadership of the Tories was open and constant. Then an Argentinian General struggling to stay in power domestically handed Thatcher the political lifeline she was desperate for.

Read more:

https://sputniknews.com/columnists/201904011073732008-thatcher-tax-scotl...

Read from top.

a shudder down your working spine...

Labor front-bencher Jim Chalmers reckons Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s admission that he draws inspiration from Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan will send a “shudder down the spine” of every Australian worker.

“Josh Frydenberg thinks the solution to this job crisis is to double down on trickle-down economics and even more job security,” the shadow treasurer told reporters in Brisbane on Sunday.

The late US president was an ardent advocate of “supply side” economic theories, which came to be known as “Reaganomics” and hold that large tax cuts for the wealthy trickle down through the economy.

Former Conservative UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher also took a tough stance on trade unions, reducing the number of days lost to industrial disputes from 30 million down to two million, according to Mr Frydenberg.

He believes both leaders dealt successfully with the challenges of the 1970s and 1980s.

“Thatcher and Reagan are figures of hate for the left because they were so successful,” he told ABC television’s Insiders program on Sunday.

“One got two terms, which was the maximum that you can get in the United States. Margaret Thatcher got 11 and a half years.”

He also draws inspiration from former Australian Liberal prime minister John Howard and his treasurer, Peter Costello.

“But the reality is that Thatcher and Reagan cut red tape and they cut taxes and delivered stronger economies.”

Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese was unimpressed.

“Josh Frydenberg confirms his inspiration for the economic recovery is Thatcher and Reagan which resulted in a massive increase in inequality and reduction in public services #GoodGrief,” he tweeted.

Read more:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/national/2020/07/26/frydenberg-loves-reagan-thatcher/

Read from top.

We all should (we should) know by now that trickle-down economics only favour the rich while giving bread-crumbs to workers who are left fighting like sociopaths to survive... Thatcher was only a hero of the upper crust, and she got lucky with "having to fight a war against an inferior equipped nation" — a bit like the US fighting Saddam in 2003... Both Thatcher and Reagan were helped by who else but our own Uncle Rupe who presently is doing all it can to support a flailing Scummo...

See also: http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/19033

a cruel economic order...

By THE IRISH TIMES | On 24 January 2021Mic Moroney

‘Rentier Capitalism’ is a cracking thesis on a cruel economic order. Read it and you’ll start seeing rentiers everywhere, hearing them in every news bulletin, all involved in massive anti-competitive behaviour and impoverishing the rest of society.

Originally a French term, rentier carries a vampiric odour, redolent of the Ancien Régime or the British landowning aristocracy: tapping gargantuan nourishment from the rent and toil of peasants on its vast estates.

The Irish Ascendancy were similarly perfumed by Maria Edgeworth’s novel, Castle Rackrent (1800), its crumbling pile mismanaged by the effete, dissolute family heirs. Decades before the Famine, “rackrent” became the catchphrase for brutally excessive rents extracted on pain of dispossession, perhaps even death on the roads.

Rentiership is now deeply embedded in business, as forensically elaborated in this tome by Brett Christophers, an Englishman by accent and an economic geographer at Sweden’s Uppsala University. Christophers historicises “rent” from its introduction into Western economic thought by Adam Smith and David Ricardo (with whom Edgeworth corresponded) and later Marx; thence through the alliance of land and financial rentierisms in the late 19th century; its abeyance in the mid-20th century; and now its resurgence across every aspect of the British economy since Margaret Thatcher.

Christophers incubated this idea in his last book, The New Enclosure (2018), which took issue with author James Meek’s assertion that Britain’s largest privatisation was the sale of council houses after Thatcher’s Right to Buy scheme for social tenants, worth “£40 billion in its first 25 years”.

But Christophers tunneled deeper. Since Thatcher’s premiership, the state had actually sold two million hectares, about 10 per cent of the entire British landmass – some, certainly under council houses, but mostly through countless land sales by cash-strapped local councils, the NHS, universities estates, school playing fields and the disastrous dumping of the ministry of defence housing stock. It all totted up to about £400 billion. The scale of it had never been publicly recognised.

Monopoly

This vast, ongoing privatisation is in keeping with Christophers’s Rentier thesis. He economically defines “rent” as income derived from the exclusive ownership and/or control of a scarce asset under conditions of limited or no competition, for example, monopoly. A rentier – an individual or, more often, a corporation that controls the asset – engulfs this income.

Rentier capitalism is thus an economic order based on wealth and income-generating assets, which are “sweated” to absorb “unearned” rents and indeed profits from the inflation in value of land assets. The British economy, Christophers maintains, is dominated by rentiers. Orientated around “owning” rather than “doing”, there is nothing innovative or entrepreneurial about rentiership. It produces nothing; just suctions in more of the wealth pie, impoverishing the rest of society.

Heated arguments about rentierism have exploded across academia and financial journalism since Thomas Piketty’s first big book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013). In Piketty’s “society of petits rentiers”, if we own property or stocks, we’re all part of it. If not, we’re suckers.

So Christophers sets out to clarify the field in a Herculean exercise of creative taxonomy, dividing up rents into seven main categories. The centrality of government is key; setting the “rules” and often “creating” assets by issuing exclusive oil exploration licences (to generate “natural resource rents” for the holders); or granting exclusive outsourcing contracts (contract rents) – both purely legal, rather than physical, constructs.

Another asset-class is physical infrastructure, particularly that delivering water, energy or telecommunications – such utilities generally regarded as “natural monopolies”. Then there’s intellectual property (IP) rentierism in patents, brands and copyright – so tasty to the pharmaceutical, consumer products and creative industries.

Meanwhile, platforms – and especially digital platforms – profit from hosting and powerfully controlling where and how trade happens, whether on Amazon, eBay, Moneysupermarket or the London Stock Exchange, which also owns and operates the Borsa Italiana.

And there are financial assets, such as shares, securities and other exotic instruments and their “rents” received by the financial rentier: John Maynard Keynes’ “functionless investor” whom, in the midst of the Great Depression, he wished to see “euthanised”.

Although finance increasingly overlooms all economies, Christophers does not rate the gathering literature on “financialisation”. He sees finance as maybe the “leading edge of rentier capitalism” but it’s “not the totality of our economic moment”.

Land

Lastly, there is his rich chapter on land: the root of all rentierism, some might say. The land-holding companies Christophers examines are all “almost comically profitable”.

The more technical passages will prove arduous for some but it’s all crackling, shimmering stuff – even if every eye-watering anecdote, trillion-pound outrage or historical sweetmeat is but an ornament to the sustained, bludgeoning monofocus of his thesis.

After days wading through it, you’ll start seeing rentiers everywhere, hearing them in every news bulletin, or envisioning how they all interlock like a lattice of money-pipes, situated at almost every choke point in supply, and all involved in massive anti-competitive behaviour.

But it’s impossible to encapsulate here the complexity, sleuthery and scope of Christophers’ inquiry. He’s a prolific writer of sprawling, argumentative prose and a furiously earnest grafter: laboriously plotting graphs from multiple data-sets; compiling tables such as the dizzying one of all major Thatcherite privatisations, from port and docks to ship building, telecoms, British Steel, oil, gas, coal, electricity, rail, air traffic control, defence technology, nuclear power, even the Royal Mail.

In another, he categorises the major infrastructure rentiers and the entities that co-control them: shadowy holding companies; global investment consortia, pension funds; even the Kuwait Investment Authority – which, although Christophers doesn’t mention it, is classified as a rentier state.

The book is entirely UK-specific, but highly instructive in the Irish context of growing privatisation of health and social care; rampant landbanking; the mushrooming of tax-sheltered REITs; or the latest long-lease social housing scheme, where the state pays the mortgage for 25 years, then the property reverts to the developer.

Christophers is rightly encouraged by more than 500 successful examples since 2000 of “remunicipalisations” across continental Europe – where disastrously privatised public services have been taken back into public or community ownership: from energy and water supply to waste collection, social care and local transport.

Unthinkable here? Last year, the pandemic saw mass changes in social activity that astonished even behavioural “scientists”. Now, as we blink in the uncertain dawn of Brexit, facing a second economic devastation this century, it might not beyond the bounds of possibility.

Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? by Brett Christophers, published by Verso.

This is a repost from The Irish Times. See the original article here.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/theres-nothing-entrepreneurial-about-rentier-capitalism-as-it-sucks-up-more-of-the-wealth-pie/

Read from top.