Search

Recent comments

- patriotism....

3 hours 55 min ago - belittling russia......

4 hours 22 min ago - Запад толкает Украину на последнюю битву....

4 hours 36 min ago - fourteen points....

4 hours 45 min ago - der philosophische glaube....

4 hours 56 min ago - seriously?...

5 hours 11 min ago - AfD....

5 hours 38 min ago - undesirables...

5 hours 54 min ago - assistant spies......

6 hours 20 min ago - brics.....

9 hours 27 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

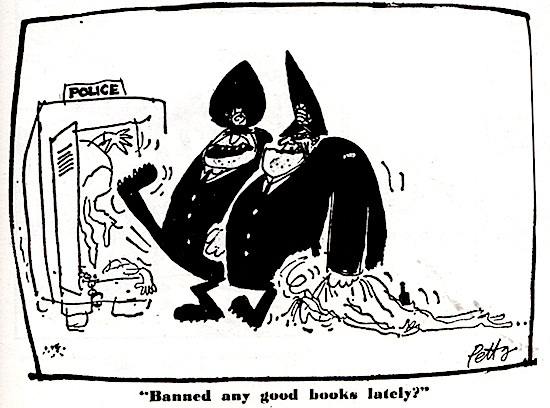

rapidly expanding anti-free speech movement...

Why Burn Books When You Can Ban Them? Writers and Publishers Embrace Blacklisting In An Expanding American Anti-Free Speech Movement

by JONATHAN TURLEY

Hundreds of publishing officials, professors, and academics have signed a petition to blacklist Trump administration alumni from receiving book deals. It is the latest step in a rapidly expanding anti-free speech movement in the United States. In the wake of the Capitol riot, Democratic members and others are calling for a crackdown on free speech and punitive actions for those viewed as complicit with Trump. What is striking is how censorship, blacklists, and speech controls are being repackaged as righteous and virtuous. Indeed, the failure to sign such anti-free speech screeds is a precarious choice for many. It is as easy as calling for tolerance through intolerance. After all, why burn books if you can just effectively ban them?

We are coming out of the most divisive and consequential political period in modern history. Academics would ordinarily want to have insider accounts, even from those who are blamed for excesses or wrongdoing. You did not have to like Nixon to want to read his account. This is part of the intellectual mission of our profession. However, academics are lining up to silence or bar access for anyone deemed a fellow traveler with Trump. They are seeking to purge books of opposing views or accounts. The letter describes a blacklisting of anyone deemed to have “enabled, promulgated, and covered up crimes against the American people.”

Hundreds signed a letter that compares former Trump associates to seeking profits to those barred under the Son of Sam law, a law named for a serial killer. The letter declares: “We are writers, editors, journalists, agents, and professionals in multiple forms of publishing. We believe in the power of words and we are tired of the industry we love enriching the monsters among us, and we will do whatever is in our power to stop it. that.” Of course, these enablers, promulgators, and conspirators were not charged with crimes except for a hand few. Nevertheless, they are all to be given the Son of Sam treatment and blocked from book deals. What these academics and writers are unwilling to do is to allow readers to make up their own minds in whether to read the first-person accounts of the controversies of the last four years.

The campaign has been remarkably successful — as has the overall anti-free speech movement. Simon and Schuster Publishing canceled the publication of Sen. Josh Hawley’s (R-Mo.) book after he objected to the certification of electoral votes.

We have been discussing the rising threats against Trump supporters, lawyers, and officials in recent weeks from Democratic members are calling for blacklists to the Lincoln Project leading a a national effort to harass and abuse any lawyers representing the Republican party or President Trump. Others are calling for banning those “complicit” from college campuses while still others are demanding a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” to “hold Trump and his enablers accountable for the crimes they have committed.” Daily Beast editor-at-large Rick Wilson has added his own call for “humiliation,” “incarceration” and even ritualistic suicides for Trump supporters in an unhinged, vulgar column.

This is building into the most dangerous anti-free speech movement in modern history. The Red Scare was largely opposed by the media and universities. This movement has the support of both. The left is proving far better at this than the right in the McCarthy period. They are using companies to achieve what anti-communists only dreamt of in the 1950s. As I have previously written, we are witnessing the death of free speech on the Internet and on our campuses. What is particularly concerning is the common evasion used by academics and reporters that this is not really a free speech issue because these are private companies. The First Amendment is designed to address government restrictions on free speech. As a private entity, companies like Twitter or publishing houses are not the subject of that amendment. However, private companies can still destroy free speech through private censorship. It is called the “Little Brother problem.” President Trump can be chastised for converting a “Little Brother” into a “Big Brother” problem. However, that does alter the fundamental threat to free speech. This is the denial of free speech, a principle that goes beyond the First Amendment. Indeed, some of us view free speech as a human right.

Consider racial or gender discrimination. It would be wrong regardless if federal law only banned such discrimination by the government. The same is true for free speech. The First Amendment is limited to government censorship, but free speech is not limited in the same way. Those of us who believe in free speech as a human right believe that it is morally wrong to deny it as either a private or governmental entity. That does not mean that there are not differences between governmental and private actions. For example, companies may control free speech in the workplaces. They have a recognized right of free speech. However, the social media companies were created as forums for speech. Indeed, they sought immunity on the false claim that they were not making editorial decisions or engaging viewpoint regulation. No one is saying that these companies are breaking the law in denying free speech. We are saying that they are denying free speech as companies offering speech platforms.

Read more:

See also: in paradise, they don't have to prune trees... — ugs isykloen

- By Gus Leonisky at 24 Jan 2021 - 2:37pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

"the challenge trump posed to objectivity"...

Traditional newspapers never sold news; they sold an audience to advertisers. To a considerable degree, this commercial imperative determined the journalistic style, with its impersonal voice and pretense of objectivity. The aim was to herd the audience into a passive consumerist mass. Opinion, which divided readers, was treated like a volatile substance and fenced off from “factual” reporting.

The digital age exploded this business model. Advertisers fled to online platforms, never to return. For most newspapers, no alternative sources of revenue existed: as circulation plummets to the lowest numbers on record, more than 2,000 dailies have gone silent since the turn of the century. The survival of the rest remains an open question.

Led by the New York Times, a few prominent brand names moved to a model that sought to squeeze revenue from digital subscribers lured behind a paywall. This approach carried its own risks. The amount of information in the world was, for practical purposes, infinite. As supply vastly outstripped demand, the news now chased the reader, rather than the other way around. Today, nobody under 85 would look for news in a newspaper. Under such circumstances, what commodity could be offered for sale?

During the 2016 presidential campaign, the Times stumbled onto a possible answer. It entailed a wrenching pivot from a journalism of fact to a “post-journalism” of opinion—a term coined, in his book of that title, by media scholar Andrey Mir. Rather than news, the paper began to sell what was, in effect, a creed, an agenda, to a congregation of like-minded souls. Post-journalism “mixes open ideological intentions with a hidden business necessity required for the media to survive,” Mir observes. The new business model required a new style of reporting. Its language aimed to commodify polarization and threat: journalists had to “scare the audience to make it donate.” At stake was survival in the digital storm.

The experiment proved controversial. It sparked a melodrama over standards at the Times, featuring a conflict between radical young reporters and befuddled middle-aged editors. In a crucible of proclamations, disputes, and meetings, the requirements of the newspaper as an institution collided with the post-journalistic call for an explicit struggle against injustice.

The battleground was the treatment of race and racism in America. But the story began, as it seemingly must, with that inescapable character: Donald Trump.

In August 2016, as the presidential race ground grimly onward, the New York Times laid down a marker regarding the manner in which it would be covered. The paper declared the prevalence of media opinion to be an irresistible fact, like the weather. Or, as Jim Rutenberg phrased it in a prominent front-page story: “If you view a Trump presidency as something that is potentially dangerous, then your reporting is going to reflect that.” Objectivity was discarded in favor of an “oppositional” stance. This was not an anti-Trump opinion piece. It was an obituary for the values of a lost era. Rutenberg, who covered the media beat, had authored a factual report about the death of factual reporting—the sort of paradox often encountered among the murky categories of post-journalism.

The article touched on the fraught issue of race and racism. Trump opponents take his racism for granted—he stands accused of appealing to the worst instincts of the American public, and those who wish to debate the point immediately fall under suspicion of being racists themselves. The dilemma, therefore, was not whether Trump was racist (that was a fact) or why he flaunted his racist views (he was a dangerous demagogue) but, rather, how to report on his racism under the strictures of commercial journalism. Once objectivity was sacrificed, an immense field of subjective possibilities presented themselves. A vision of the journalist as arbiter of racial justice would soon divide the generations inside the New York Times newsroom.

Rutenberg made his point through hypothetical-rhetorical questions that, at times, verged on satire: “If you’re a working journalist and you believe that Donald J. Trump is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators and that he would be dangerous with control of United States nuclear codes, how the heck are you supposed to cover him?” Rutenberg assumed that “working journalists” shared the same opinion of Trump—that wasn’t perceived as problematic. A second assumption concerned the intelligence of readers: they couldn’t be trusted to process the facts. The answer to Rutenberg’s loaded question, therefore, could only be to “throw out the textbook American journalism has been using for the better part of a half-century” and leap vigorously into advocacy. Trump could not safely be covered; he had to be opposed.

The old media had needed happy customers. The goal of post-journalism, according to Mir, is to “produce angry citizens.” The August 2016 article marked the point of no return in the spiritual journey of the New York Times from newspaper of record to Vatican of liberal political furor. While the impulse originated in partisan herd instinct, the discovery of a profit motive would make the change irrevocable. Rutenberg professed to find the new approach “uncomfortable” and, “by normal standards, untenable”—but the fault, he made clear, lay entirely with the “abnormal” Trump, whose toxic personality had contaminated journalism. He was the active principle in the headline “The Challenge Trump Poses to Objectivity.”

A cynic (or a conservative) might argue that objectivity in political reporting was more an empty boast than a professional standard and that the newspaper, in pandering to its audience, had long favored an urban agenda, liberal causes, and Democratic candidates. This interpretation misses the transformation in the depths that post-journalism involved. The flagship American newspaper had turned in a direction that came close to propaganda. The oppositional stance, as Mir has noted, cannot coexist with newsroom independence: writers and editors were soon to be punished for straying from the cause. The news agenda became narrower and more repetitive as journalists focused on a handful of partisan controversies—an effect that Mir labeled “discourse concentration.” The New York Times, as a purveyor of information and a political institution, had cut itself loose from its own history.

Rutenberg glimpsed, dimly, the nature of the transfiguration he was describing. “Do normal standards apply? And if they don’t, what should take their place?” he wondered. Even if rhetorically framed, these were remarkable questions. Over the next four years, the need for answers would feed the drama in the Times newsroom.

There’s reason to suspect that Rutenberg and his colleagues regarded the abandonment of objectivity as a temporary emergency measure. Hillary Clinton was heavily favored in opinion polls; on election day, the Times gave her an 84 percent chance of victory. The election of Donald Trump to the presidency was a moment of profound disorientation for establishment media generally, and for the Times in particular.

Not only had the newspaper failed at the new mission of advocacy; it had also failed, egregiously, at the old mission of mediating between the public and the elite sport of politics. In a somber column published the morning after, Liz Spayd, public editor, announced that the Times had entered “a period of self-reflection” and expressed the hope that “its editors will think hard about the half of America the paper too seldom covers.”

The reflective mood quickly passed. Within weeks, the Washington Post connected the Trump campaign with fake news on Facebook planted by Russian operatives. By May 2017, less than four months into the new administration, Robert Mueller had been appointed special counsel to investigate potential crimes by Trump or his staff associated with Russian interference in the elections. So began one of the most extraordinary episodes in American politics—and the first sustained excursion into post-journalism by the American news media, led every step of the way by the New York Times.

Future media historians may hold the Trump-Russia story to be a laboratory-perfect specimen of discourse concentration. For nearly two years, it towered over the information landscape and devoured the attention of the media and the public. The total number of articles on the topic produced by the Times is difficult to measure, but a Google search suggests that it was more than 3,000—the equivalent, if accurate, of multiple articles per day for the period in question. This was journalism as if conducted under the impulse of an obsessive-compulsive personality. Virtually every report either implied or proclaimed culpability. Every day in the news marked the beginning of the Trumpian End Times.

The sum of all this sound and fury was . . . zero. The most intensively covered story in history turned out to be empty of content. Mueller’s investigation “did not identify evidence that any US persons conspired or coordinated” with the Russians. Mueller’s halting television appearance in July 2019 convinced even the most vehement partisans that he was not the knight to slay the dragon in the White House. After two years of media frenzy came an awkward moment. The New York Times had reorganized its newsroom to pursue this single story—yet, just as it had missed Trump’s coming, the paper failed to see that Trump would stay.

Yet what looked like journalistic failure was, in fact, an astonishing post-journalistic success. The intent of post-journalism was never to represent reality or inform the public but to arouse enough political fervor in readers that they wished to enter the paywall in support of the cause. This was ideology by the numbers—and the numbers were striking. Digital subscriptions to the New York Times, which had been stagnant, nearly doubled in the first year of Trump’s presidency. By August 2020, the paper had 6 million digital subscribers—six times the number on Election Day 2016 and the most in the world for any newspaper. The Russian collusion story, though refuted objectively, had been validated subjectively, by the growth in the congregation of the paying faithful.

In throwing out the old textbook, post-journalism made transgression inevitable. In July 2019, Jonathan Weisman, who covered Congress for the Timesand happened to be white, questioned on Twitter the legitimacy of leftist members of the House who happened to be black. Following criticism, Weisman deleted the offending tweets and apologized elaborately, but he was demoted nonetheless.

Then, in August, the print edition of the newspaper covered a presidential statement under the headline “Trump Urges Unity vs. Racism.” Before that could be changed, a storm of outrage swept over social media and penetrated into the Times’s newsroom. Condemnation of Trump as the avatar of American racism was as close to a canonical doctrine as the new style of reporting possessed. Deviation was cause for scandal. Internal turmoil forced Dean Baquet, the paper’s executive editor, to hold a “town hall” meeting with his newsroom staff, the transcript of which was obtained and published by Slate.

The dramatic confrontation had been triggered by Weisman’s tweets and the heretical headline but was really about the boundaries of expression—what was allowed and what was taboo—in a post-objective, post-journalistic time. On the contentious subjects of Trump and race, managers and reporters at the paper appeared to hold similar opinions. No one in the room defended Trump as a normal politician whose views deserved a hearing. No one questioned the notion that the United States, having elected Trump, was a fundamentally racist country. But as Baquet fielded long and pointed questions from his staff, it became clear that management and newsroom—which translated roughly to middle age and youth—held radically divergent visions of the post-journalism future.

Baquet and his editors wished to pursue an institutional approach to advocacy. The influence that the New York Times wields was a function of its standing among other powerful American institutions: so if you wanted to defeat Donald Trump, you needed to maintain the proper tone. In his answers, Baquet, who was 62, often compared the Times favorably to other news organizations and referred to its storied past. When asked repeatedly why, if everyone agreed that Trump was a racist, the use of the word itself was taboo, Baquet turned to the history of the civil rights movement. The best reporters who covered that struggle, he said, by describing injustice had delivered a message “more powerful” than any epithet.

Baquet admitted that the survival of Trump after the Mueller investigation had caught the newspaper “a tiny little bit flat-footed.” “Our readers who want Donald Trump to go away suddenly thought, ‘Holy shit, Bob Mueller is not going to do it.’ ” Given the business model, a new scheme of polarization was needed. Baquet proposed to cover “race and class in a deeper way than we have in years.”

To the young warriors of the newsroom, this probably sounded like rank hypocrisy. Many belonged to a generation uninterested in history that perceived social life in terms of a cosmic conflict against injustice. Their questions suggested that post-journalism, to them, meant telling the unvarnished truth—which happened to be identical to their political convictions. If Trump lied or made racist statements, journalists had a moral duty to call him out as a liar and a racist. This principle was absolute and extended to all subjects. Since, as one of them put it, “racism and white supremacy” had been “sort of the foundation of this country,” the consequences should be reported explicitly. “I just feel like racism is in everything,” this questioner asserted. “It should be considered in our science reporting, in our culture reporting, in our national reporting.”

Unlike management, the reporters were active on social media, where they had to face the most militant elements of the subscriber base. In this way, they represented the forces driving the information agenda. Baquet had disparaged Twitter and insisted that the Times would not be edited by social media. He was mistaken. The unrest in the newsroom had been propelled by outrage on the web, and the paper had quickly responded. Generational attitudes, displayed on social media, allowed no space for institutional loyalty. Baquet had demoted Weisman because of his inappropriate behavior—but the newsroom turned against him because he had picked a fight with the wrong enemy.

To the sectarian mind, all institutions are sinful. “I am concerned,” warned a staffer at the town hall meeting, “that the Times is failing to rise to the challenge of a historical moment.” In the final act of the drama, that concern would explode into revolt. When the young reporters proclaimed that racism was everywhere, they were casting a judgmental eye on their bosses.

Two days after the town hall meeting, the New York Times inaugurated, in its magazine section, the “1619 Project”—an attempt, said Baquet, “to try to understand the forces that led to the election of Donald Trump.” Rather than dig deep into the “half of America” that had voted for the president, the newspaper chose to blame the events of 2016 on the country’s pervasive racism, not only here and now but everywhere and always.

The 1619 Project rode the social-justice ambitions of the newsroom to commodify racial polarization—and, not incidentally, to fill the void left by Robert Mueller’s failure to launch. The project showed little interest in investigative reporting or any other form of old-school journalism. It produced no exposés of present-day injustice. Instead, it sold agenda-setting on a grand scale: the stated mission was to “reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the center of our national narrative.” The reportorial crunch implicit in this high-minded posture might be summarized as “All the news that’s fit to reframe history.”

The guiding spirit behind the 1619 Project was Nikole Hannah-Jones, a rising star at the Times and a practitioner of the prosecutorial school of post-journalism. In a long essay that introduced the project, Hannah-Jones placed American history in the defendant’s docket and found it guilty of unrelieved injustice and oppression. The cast of thousands and multiple plot twists of that story were quite literally reduced to black and white, with whites eternally the villains and falsifiers—not even Lincoln came off looking good—and blacks as redeemers of the nation. “Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written,” the article began. “Black Americans have fought to make them true.”

The 1619 Project has come under fire for its extreme statements and many historical inaccuracies. Yet critics missed the point of the exercise, which was to stake out polarizing positions in the mode of post-truth: opinions could be transformed into facts if held passionately enough. The project became another post-journalistic triumph for the Times. Public school systems around the country have included the material in their curricula. Hannah-Jones received a Pulitzer Prize for her “sweeping, provocative, and personal essay”—possibly the first award offered for excellence in post-journalism. The focus on race propelled the Times to the vanguard of establishment opinion during the convulsions that followed the death of George Floyd under the knee of a white Minneapolis police officer in May 2020.

That episode replaced the Russia collusion story as the prime manufacturer of “angry citizens” and added an element of inflexibility to the usual rigors of post-journalism. Times coverage of antipolice protests was generally sympathetic to the protesters. Trump was, of course, vilified for “fanning the strife.” But the significant change came in the severe tightening of discourse: the reframing imperative now controlled the presentation of news. Reporting minimized the violence that attended the protests, for example, and sought to keep the two phenomena sharply segregated.

News out of step with the reframing mission was exiled to the opinion pages—a loophole that would bring to a climax the family melodrama within the organization. Less than two weeks after Floyd’s death, amid spreading lawlessness in many American cities, the paper posted an opinion piece by Republican senator Tom Cotton in its online op-ed section, titled “Time to Send in the Troops.” It called for “an overwhelming show of force” to pacify troubled urban areas. To many loyal to the New York Times, including staff, allowing Cotton his pitch smacked of treason. Led by young black reporters, the newsroom rebelled.

Once again, the mutiny began on Twitter. Many reporters had large followings; they could appeal directly to readers. In the way of social media, the most excited voices dominated among subscribers. As the base roared, the rebels moved to confront their employer.

The day after the Cotton op-ed appeared online, Times employees sent a letter to Times decision makers, expressing “deep concern” over the piece. This document marked the logical culmination of the process that Rutenberg’s article had begun four years earlier. Objectivity now jettisoned, the question at hand was whose subjective will should control the news agenda.

The letter’s authors made a number of striking assumptions. First, the backdrop was an apocalyptic struggle between good and evil, a story “that does not have a direct precedent in our lifetimes.” The place of the New York Times in that struggle was at issue. Second, some opinions were dangerous—physically so. Cotton’s opinion fell into that category. “Choosing to present this point of view without added context leaves members of the American public . . . vulnerable to harm” while also jeopardizing “our reporters’ ability to work safely and effectively.” Third, the duty of the newspaper was less to inform than to protect such “vulnerable” readers from harmful opinions. By allowing Cotton inside the tent, the Times had failed its readership.

This was the essence of post-journalism: informational “protection”—polarization—sold as a commodity. Objectivity had crumbled before the dangerous Trump. On the question of who decided the danger of any given piece, the newsroom rebels presented a number of broad demands. Future opinion pieces needed to be vetted “across the desk’s diverse staff before publication,” while readers should be invited to “express themselves.” The young reporters felt that they had a better fix on what readers wanted than did their elders. Given the generational divide on social media, this was almost certainly true.

The letter triggered yet another town hall meeting, this time with opinion-page editor James Bennet. It did not go well. Two days later, Bennet was fired. As the rebels demanded, the Cotton op-ed was detoxified with a long-winded editor’s note. The op-ed never appeared in the Times’s print edition. The influence over the news agenda of the younger, more radical, newsroom voices, we can infer, was now large and growing. Older reporters and editors were unlikely to confront them: none wished to share Bennet’s fate.

The history-reframing mission is now in the hands of a deeply self-righteous group that has trouble discerning the many human stopping places between true and false, good and evil, objective and subjective. According to one poll, a majority of Americans shared the opinion that Cotton expressed in his op-ed. That had no bearing on the discussion. In the letter and the town hall meetings, the rebels wielded the word “truth” as if they owned it. By their lights, Cotton had lied, and the fact that the public approved of his lies was precisely what made his piece dangerous.

Two weeks after the Cotton controversy, the Times published an essay by Wesley Lowery, a Pulitzer Prize–winning black reporter, titled “A Reckoning over Objectivity, Led by Black Journalists.” Equating objectivity with “whiteness,” Lowery called for “moral clarity, which will require both editors and reporters to stop doing things like reflexively hiding behind euphemisms to obfuscate the truth.” The Trump administration and the Republican Party, Lowery urged, should be labeled as what they are: a “refuge to white supremacist rhetoric and policies.” In the post-Bennet moment of post-journalism, editors at the paper were inclined to agree.

Revolutions tend to radicalization. The same is true of social media mobs: they grow ever more extreme until they explode. But the New York Times is neither of these things—it’s a business, and post-journalism is now its business model. The demand for moral clarity, pressed by those who own the truth, must increasingly resemble a quest for radical conformism; but for nonideological reasons, the demand cannot afford to leave subscriber opinion too far behind. Radicalization must balance with the bottom line.

The final paradox of post-journalism is that the generation most likely to share the moralistic attitude of the newsroom rebels is the least likely to read a newspaper. Andrey Mir, who first defined the concept, sees post-journalism as a desperate gamble, doomed in the end by demographics. For newspapers and their multiple art forms developed over a 400-year history, Mir writes, the collision with the digital tsunami was never going to be a challenge to surmount but rather “an extinction-level event.”

Martin Gurri is a former CIA analyst and the author of The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium.

Read more:

https://www.city-journal.org/journalism-advocacy-over-reporting

See also:

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/37153

http://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/36783

a bill to create a revolution...

Among the MAGA flags and “Stop the Steal” signs that festooned the sea of rioters who invaded the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 was the abundant stamp of another conspiracy movement—QAnon—that nursed the election-fraud lies that fueled the crowd.

Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-FL) was already struck at how the Capitol attack demonstrated the growing influence of conspiracy theories like QAnon—a wide-ranging set of unfounded beliefs encompassing election lies and fantasies of depravity by those in power—which drove adherents to a violent plot to keep Donald Trump in power by any means necessary.

Then came the report that at least 22 current or former members of the U.S. military or law enforcement were found to have been at or near the Capitol attack on Jan. 6, according to a Jan. 15 review by the Associated Press, with more reportedly under investigation by federal officials.

A former Pentagon official, Murphy quickly drew up a bill designed to block QAnon believers, and other conspiracy followers, from obtaining the security clearances required to access classified federal government information.

“What we discovered was that there was a shocking number of people involved in that insurrection who seemingly live normal lives, working in government and law enforcement and the military,” Murphy told The Daily Beast. “It’s really dangerous for individuals who hold these types of views to receive a security clearance and access to classified information… if any Americans participated in the Capitol attack, or if they subscribe to these dangerous anti-government views of QAnon, then they have no business being entrusted with our nation's secrets.”

Murphy’s bill, one of the first legislative efforts crafted in response to the terror on display two weeks ago, is a sign of how sharply the policy agenda of Congress and President Joe Biden in the coming weeks and months has shifted with respect to right-wing extremism.

At her Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday, Avril Haines, Biden’s choice for intelligence chief, pledged to produce a public threat assessment of QAnon, using intelligence compiled by the 18 agencies under her umbrella as director of national intelligence. And Alejandro Mayorkas, the nominee to head up the Department of Homeland Security, also vowed to ramp up the agency’s efforts to tackle domestic extremism in his Tuesday confirmation hearing.

Murphy’s bill is another concrete sign of how much more seriously Capitol Hill is taking the QAnon movement specifically, which—aside from a symbolic House resolution condemning the conspiracy in October—has gotten scant attention from lawmakers as it spread around the country in recent years. Murphy, a moderate Democrat with a track record of passing bills with Republican backing, said she is courting GOP colleagues to cosponsor the bill and expects it will gain bipartisan support.

Jared Holt, a research fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab and an expert in right-wing extremism, said it was “refreshing” to see bills like Murphy’s emerge. “Congress is way behind the ball, and any sort of meaningful confrontation with the issue is going to require a good deal of catch-up,” Holt told The Daily Beast.

The legislation, titled the Security Clearance Improvement Act of 2021, requires applicants looking to obtain or renew their federal security clearances to disclose if they participated in the Jan. 6 rally in Washington—or another “Stop the Steal” event—or if they “knowingly engaged in activities conducted by an organization or movement that spreads conspiracy theories and false information about the U.S. government.”

That question would be included among the other questions asked of applicants in the lengthy questionnaire, called the Standard Form 86, required to gain a clearance, which, under federal law, “shall be granted only to employees… for whom an appropriate investigation has been completed and whose personal and professional history affirmatively indicates loyalty to the United States, strength of character, trustworthiness, honesty, reliability, discretion, and sound judgment.”

But Denver Riggleman, a former Republican congressman and intelligence official who was the GOP’s loudest QAnon critic during his time in Congress, said that the SF-86 already asks applicants if they had ever supported an overthrow of the U.S. government. Riggleman—who said he’s filled out the SF-86 “six or seven times”—argued that adding a question to screen for QAnon beliefs might be redundant, become a slippery slope to encompassing other conspiracies, or ensnare people who don’t believe in the most extreme theories.

But Riggleman, who cosponsored the QAnon condemnation resolution with Rep. Tom Malinowski (D-NJ), agreed that security clearance screening needs to be updated for the realities of 2021. “Instead of an overarching QAnon [question], look at the most damaging parts of the disinformation plague we have,” he suggested, proposing language that asks about any association with “deep state cabals and coups” and other phrases common with far-right conspiracies.

“Because disinformation, it encapsulates so many ridiculous notions,” said Riggleman. “If you had someone go to ‘Stop the Steal,’ and thought there were white vans with burning ballots, that’s a bit different than thinking babies were harvested in Epstein’s temple.”

Another issue with a question on an applicant’s QAnon association, of course, is that they might not answer it truthfully, knowing it could imperil their chance of securing a clearance. And in recent days, QAnon threads have urged followers to “camouflage” and avoid using the term QAnon in order to evade detection in the aftermath of Jan. 6, said Travis View, an expert on the movement.

Still, with background checkers able to screen social media and other channels for support of such conspiracy theories, they could ascertain whether applicants answered Murphy’s proposed question untruthfully—which, on its own, would be grounds to revoke or block the issuing of a security clearance. It is also a federal crime to lie on the SF-86.

Holt said the bill has noble goals but expressed concern that it could be implemented in a way that roots out QAnon adherents and other extremists from positions of national security importance. “QAnon is such a decentralized movement—it’s more of a digital oriented community,” he said. “I don’t know if being part of Pepe’s united Facebook group would get picked up on this [background check.]”

“So many people are looking for a silver bullet solution to this, but it’s this weird, complex, nuanced thing,” Holt continued. “It will take a multitude of actions to address meaningfully.”

Murphy would not disagree. It is not lost on her that she is proposing this legislation when at least one colleague, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), was elected while having professed support for QAnon. Other Republicans have reportedly been linked to the organizers of the Jan. 6 rally.

Under Murphy’s proposal, these lawmakers might be barred from access to sensitive information—were they not members of Congress, who merely have to sign documents after their swearing-in in order to begin receiving briefings on classified national security and intelligence topics.

“It's a privilege that's afforded to us through our position,” said Murphy. “But I think this privilege should have its limits. And I certainly hope that this starts a conversation about holding accountable those members of Congress who share these extreme views and potentially, barring them from accessing classified information, especially if they have previously participated in efforts to overthrow the government, or have been motivated by their belief in these conspiracies to harm the United States or any of our elected officials.”

Riggleman agreed that Murphy’s bill could get GOP support, in the wake of the Jan. 6 attack that touched every member of Congress. But he couldn’t help but recall his own experience working with Malinowski on the QAnon resolution last year—and believes similar dynamics are at play as Congress embarks on a real policy effort to counter violent extremism.

“It was really unfortunate. No one wanted to even identify the problem, to have a policy discussion about it,” he said. “I was the only Republican to speak on the floor for it. I gotta tell you, that was a very lonely day.”

House GOP leadership, said Riggleman, fought him on the push, saying it was a First Amendment issue—a “bullshit” argument, in his words. “It was going to isolate their constituents and cause them to lose a primary, and they didn’t want to deal with it.”

If he and Malinowski had moved to pass that resolution today, Riggleman predicted, “I still think we’d get a basketball team worth of people” on the GOP side willing to speak in favor of it. “But there are three basketball teams worth of crazy in the Republican Party right now.”

Read more:

https://www.thedailybeast.com/dems-new-bill-aims-to-bar-qanon-followers-from-security-clearances

Read from top.

Sure. The Democrats are all angels who blow trumpets for the Pentagon and the Republicans are all demons who blow trumpets for Trump... Trying to kill the demons by decree can only precipitate A nasty REVOLUTION. Meanwhile there are quite a few problems with "the vaccines". Because of the rush and of the very limited testing, some vaccines have shown to be iffy, but the Main Stream Media is harping on the benefits rather than the problems... because should you refuse vaccination, you're a scab, a pox, a flotsam who will be refused boarding planes and entry in all other countries: staying at home sounds nice.

Some vaccines have been "dropped" from research and manufacture (Merck) while so far it looks like the Sputnik V could be the best, but the West does not like it because a) it's Russian, b) it does not offer making huge amount of cash through patents c) government are prepared to buy at inflated prices anything that look like a vaccine, except a Rusky one.

A European country, Hungary, "has been allowed" by Brussel to get the Sputnik vaccine, possibly to allow other EU countries get the other vaccines, manufactured in the West, and help diminish the "shortage" of vaccines... (for which Trump has been blamed for by Team Biden)...

we'll shut you up...

Stand Down @Jack: Why The First Amendment Needs To Be Applied To Social Media

In the wake of Trump's Twitter ban, big tech can't be allowed to hide behind terms and conditions any longer.

By Peter Van Buren

The interplay between the First Amendment and corporations like Twitter, Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook is the most significant challenge to free speech in our lifetimes. Pretending a corporation with the reach to influence elections is just another place that sells stuff is to pretend the role of debate in a free society is outdated.

From the day the Founders wrote the 1A until very recently, no entity existed that could censor on the scale of big tech other than the government. It was difficult for one company, never mind one man, to silence an idea or promote a false story in America, never mind the entire world. That was the stuff of Bond villains.

The arrival of global technology controlled by mega-corporations like Twitter brought first the ability the control speech and soon after the willingness. The rules are their rules, and so do we see the permanent banning of a president for whom some 70 million Americans voted from tweeting to his 88 million followers (ironically the courts had earlier claimed it was unconstitutional for the president to block those who wanted to follow him). Meanwhile, the same censors allowed the Iranian and Chinese governments (along with the president’s critics) to speak freely. For these companies, violence in one form is a threat to democracy while violence in another similar form is valorized under a different colored flag.

The year 2020 also saw the arrival of a new tactic by the global media: sending a story down the memory hole to influence an election. The contents of Hunter Biden’s laptop, which strongly suggest illegal behavior on his part and unethical behavior by his father the president, were purposefully and effectively kept from the majority of voters. It was no longer for a voter to agree or disagree; it was to know and judge yourself or remain ignorant and just vote anyway.

Try an experiment. Google “Peter Van Buren” with the quote marks. Most of you will see on the first page of results articles I wrote four years ago for outlets like The Nation and Salon. Almost none of you will see the scores of columns I’ve written for The American Conservative over the past four years. Google buries them.

The ability of a handful of people nobody voted for to control the mass of public discourse has never been clearer. It represents a stunning centralization of power. It is this power that negates the argument of “go start your own web forum.” Someone did—and then Amazon withdrew its server support and Apple and Google banned their app.

The same thing happened to the Daily Stormer, which was driven offline through a coordinated effort by the tech companies and 8Chan and deplatformed by Cloudflare. Amazon partner GoDaddy deplatformed the world’s largest gun forum AR15. Tech giants have also killed off local newspapers by gobbling up ad revenues. These companies are not, in @jack’s words, “one small part of the larger public conversation.”

The tech companies’ logic in destroying the conservative social media forum Parler was particularly evil—either start censoring like we do (“moderation”) or we shut you down. Parler allowing ideas and people banned by the others is what brought about its demise. Amazon, et al, wielded their power to censor to another company. The tech companies also claimed that while Section 230 says we are not publishers, we just provide the platform, if Parler did not exercise editorial control to big tech’s satisfaction, it was finished. Even if Parler comes back online, it will live only at the pleasure of the powerful.

Since democracy was created, it has required a public forum, from the Acropolis to the town square on down. That place exists today, for better or worse, across global media. It is the seriousness of the threat to free speech that requires us to move beyond platitudes like “it’s not a violation of free speech, just a breach of the terms of service!” People once said “I’d like to help you vote ladies, but the Constitution specifically refers to men.” That’s the side of history some are standing on.

This new reality must be the starting point, not the endpoint, of discussions about the First Amendment and global media. Facebook, et al, have evolved into something new that can reach beyond their corporate borders, beyond the idea of a company that just sells soap or cereal, beyond the vision of the Founders when they wrote the 1A. It is hard to imagine Thomas Jefferson endorsing a college dropout determining what the president can say to millions of Americans. The magic game of words—it’s a company so it does not matter—is no longer enough to save us from drowning.

Tech companies currently work in casual consultation with one another, taking turns being the first to ban something so the others can follow. The next step is when a decision by one company ripples instantly across to the others, and then down to their contractors and suppliers as a requirement to continue business. The decision by AirBnB to ban users over their political stances could cross platforms so a person could not fly, use a credit card, etc., turning him essentially into a non-person unable to participate in society beyond taking a walk. And why not fully automate the task, destroying people who use a certain hashtag, or who like an offending tweet? Perhaps create a youth organization called Twitter Jugend to watch over media 24/7 and report dangerous ideas? A nation of high school hall monitors.

Consider linkages to the surveillance technology we idolize when it helps arrest the “right” people. So with the Capitol riots do we fetishize how cell phone data was used to place people on site, coupled with facial recognition run against images pulled off of social media. Throw in calls from the media for people to turn in friends and neighbors to the FBI, alongside amateur efforts across Twitter and even Bumble to “out” participants. The goal was to jail people if possible, but most loyalists seemed equally satisfied if they could cause someone to lose their job. Tech is blithely providing these tools to users it approves of, knowing full well how they will be used. Orwellian? Orwell was an amateur.

There are legal arguments to extend limited 1A protections to social media. Section 230 could be amended. However, given that Democrats benefit disproportionately from corporate and government censorship, no legislative solution appears likely. Such people care far more about the rights of some citizens (trans people seem popular now; it used to be disabled folks) than the most basic right for all the people.

They rely on the fact that it is professional suicide today to defend all speech on principle. It is easy in divided America to claim the struggle against fascism (racism, misogyny, white supremacy, whatever) overrules the old norms. And they think they can control the beast.

But imagine that someone’s views, which today might match @jack’s and Zuck’s, change over time. Imagine that Zuck finds religion and uses all of his resources to ban legal abortion. Consider a change of technology that allows a different company, run by someone who thinks like the MyPillow Guy, to replace Google in dictating what you can read. As one former ACLU director explained, “Speech restrictions are like poison gas. They seem like they’re a great weapon when you’ve got your target in sight. But then the wind shifts.”

The election of 2020, when they hid the story of Hunter Biden’s laptop from voters, and the aftermath, when they banned the president and other conservative voices, was the coming-of-age moment, the proof of concept for media giants that they could operate behind the illusion of democracy.

Hope rests with the Supreme Court expanding the First Amendment to social media, as it did when it grew the 1A to cover all levels of government, down to the hometown mayor. The Court has long acknowledged the flexibility of the 1A in general, expanding it over the years to acts of “speech” as disparate as nudity and advertising. But don’t expect much change anytime soon. Landmark decisions on speech, like those on other civil rights, tend to be evolutionary and in line with societal changes rather than revolutionary.

It is sad that many of the same people who quoted that “First they came for…” poem about Trump’s Muslim ban are now gleefully supporting social media’s censorship of conservative voices. The funny part is that both Trump and Twitter claim what they did was for people’s safety. One day we’ll all wake up and realize it doesn’t matter who is doing the censoring, the government or Amazon. It’s all just censoring.

What a sad little argument “But you violated the terms of service nyah nyah!” is going to be then.

Peter Van Buren is the author of We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People, Hooper’s War: A Novel of WWII Japan, and Ghosts of Tom Joad: A Story of the 99 Percent.

Read more:

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/stand-down-jack-why-the-first-amendment-needs-to-be-applied-to-social-media/

Read from top

And this is the way they destroyed unionism in the USA from the 1930s onwards...

Today, unions have been swept into dusty corners of the U.S. workforce, such as Las Vegas casino cleaners and New York City hotel staff. For much of the 20th century, things were different. Almost every person living in the Northeast, Midwest and California "was in a union himself/herself, had a family member in a union, or, at least, had a friend or neighbor in a union," Rich Yeleson, veteran in the labor movement, writes in The New Republic. The apogee of the unions was also the apogee of the middle class, when it commanded more than half of total income. As the union membership rate dropped, middle class share of income fell, too.

... in "The Rise and Fall of U.S. Unions," by Emin M. Dinlersoz and Jeremy Greenwood. Boiled down to a sentence: Technological innovation gave life to the American union. Then technological innovation killed the American union.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/06/who-killed-american-unions/258239/

But it could have been the strong desire of governments to erase communism from the US lexicon that eventually killed unions in the USA in favour of "everyone for himself/herself/itself" in a competitive environment in which sociopathy can flourish better... They call it capitalism.